Henrietta Swan Leavitt

Henrietta Leavitt discovered the relationship between the luminosity (brightness) and period (length of pulsation) of Cepheid variable stars; this would be a key step in measuring distance in space, even between galaxies.

Leavitt began losing her hearing as a young woman; her colleague Annie Jump Cannon became deaf due to scarlet fever at age 30.

“Her discovery of the relation of period to brightness is destined to be one of the most significant results of stellar astronomy.”

Harlow Shapley letter to Edward Pickering, 1917

Early Life

Born July 4,1868, in Lancaster, Massachusetts, she was the eldest of seven children of a Congregationalist minister. Around 1871, her family moved to Cambridge, Mass, and later to Cleveland, Ohio. There, Leavitt enrolled at Oberlin College—which had been coeducational since it opened and was the country’s first coed college—in 1885. After completing her undergraduate course, she applied to what would become Radcliffe College, a women’s auxiliary to Harvard. While some Harvard instructors had been teaching women informally since the 1870s and this had evolved into the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women in 1879, it wouldn’t be named Radcliffe until 1894.

In order to gain admittance, Leavitt was tested on her knowledge of literature, history, mathematics, physics, astronomy, Latin, Greek and German, as well as writing a short composition. Although her history results were less than ideal, she would be allowed to “rectify this deficiency” during her time at Radcliffe. The program offered at the time emphasized the arts, with little science. She studied English, Latin, Greek, German, French, and Italian, as well as fine arts, and philosophy. On the STEM side, she took a math course covering analytic geometry and differential calculus, as well as introductory physics and, in her final year, astronomy. She graduated in 1892 with a certificate stating that, had she been a man, she would have qualified for a Bachelor of Arts.

The Observatory

Having taken her astronomy course at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO), she volunteered to work there for no pay after graduation. Edward Pickering had been director of the HCO since 1876, having previously been a physics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Pickering was known for hiring women to work at the HCO—while he was reputedly very supportive of his female employees, as we will see from Leavitt’s experience, he also freely admitted that part of his incentive for hiring them was that he could pay them less than equally (or less) qualified men. This way, he could stretch his limited budget as far as possible while still collecting as much data—such as establishing the position, color and magnitude of as many stars—as possible. So, Leavitt’s offer of free labor by an educated woman would have certainly appealed to him, and she set to work recording data from photographic plates (essentially glass photographs of the night sky).

“Dry plate photography was a brand-new technology. And what it allowed to do was these multiple-hour exposures, which gathered the starlight onto the glass plates, pulled dim stars into view, and allowed the stars to be studied en masse. So, thousands of stars could be held on a singular plate for study, versus that object by object, slow, subjective looking through the eye of a telescope. So, with this new technology came an enormous radical shift in how astronomy research was conducted,” Leavitt biographer Anna von Mertens explains. “These were plates of glass that were coated with a light-sensitive emulsion placed in a telescope, and so each star, once exposed, registered as a tiny black speck, and if you think of pepper scattered across a glass surface, that was what her data was, that was how she studied the stars. And from the study of these inverted pieces of starlight, she made this foundational discovery that changed our understanding of the cosmos.”

Figure 1. Harvard College Observatory

Because astronomers knew many stars’ brightness changes, one of her jobs was to document these variable stars, and she wrote a draft manuscript of her findings in 1896. Pickering provided feedback on this manuscript before Leavitt departed for Beloit, Wisconsin, where her father had taken a minister position. In 1900, Leavitt was living with her parents and four surviving siblings, and teaching art at Beloit College. But she remained in contact with Pickering via letters and longed to return to astronomy and work on her manuscript. In a 1902 letter, she asked Pickering to send her materials to finish the manuscript: “I am more sorry than I can tell you that the work I undertook with such delight, and carried to a certain point with such keen pleasure, should be left uncompleted.” In the letter, she also mentioned her hearing loss, which would grow progressively worse over time. It was a trait she shared with HCO colleague Annie Jump Cannon, who became deaf at age 30 due to scarlet fever.

Pickering replied immediately, offering her a full-time job at the HCO so she could finish the manuscript, paying 30 cents per hour given the “quality of (her) work,” when the usual rate was 25 cents/hour. She accepted, returning to Cambridge, where she would live with her uncle while working at the HCO. In spring 1904, she was studying plates of the Small Magellanic Cloud from the HCO’s Boyden Station in Arequipa, Peru. In the plates, she discovered, in her own works, “an extraordinary number” of variable stars. It wasn’t until 1908 that she published a 21-page account of her work, 1777 Variables in the Magellanic Clouds. At the end of this paper is a line that would prove crucial: “It is worthy of notice that the brighter variables have the longer periods.”

Leavitt continued gathering and analyzing data, establishing the relationship between the luminosity (brightness) and period (length of pulsation) of Cepheid variable stars. This would be the foundation on which others would build their methods of measuring distance in space, even between galaxies, as well as studying the expansion of the universe. As the Center for Astrophysics at Harvard explains, “This meant that if an astronomer could measure the period of any Cepheid star, they could infer its intrinsic brightness. Once a star's intrinsic brightness is known, astronomers can calculate how far away the star is by knowing how light dims the further it travels.”

Leavitt’s work was delayed by an illness that hospitalized her in December 1908; after her release, she returned to Wisconsin to recuperate with her family, spending most of 1909 there. Pickering was eager for her to resume work—when she was not well enough to travel back to Cambridge, he sent materials to work on in Beloit until she was able to return in May 1910. Her work was again interrupted the following year when the March 1911 death of her father once again sent Leavitt back to her family in Beloit (with Pickering once again sending work materials following after her), returning to HCO that autumn. She also had to take three months off in 1913 due to stomach surgery.

In a 1912 Harvard Circular, she expanded on her findings about variable stars that would later be known as Cepheid variables, noting “Since the variables are probably at nearly the same distance from the Earth their periods are apparently associated with their actual emission of light, as determined by their mass, density, and surface brightness.” This discovery allowed astronomers to determine relative distances, but Pickering did not allow Leavitt to participate in the next step: developing techniques to determine the distance to at least one of the stars to serve as a yardstick from which the relative distances could then be calculated. For years, Pickering had been prioritizing Leavitt’s time not on the variable stars, but on his own preferred project, collecting accurate data on 96 stars close to Polaris.

Astronomer Harlow Shapley, who would later take over the directorship of the HCO, was working on establishing the size of the Milky Way galaxy. He wrote to Pickering in 1917 with questions for Leavitt, and noted, “Her discovery of the relation of period to brightness is destined to be one of the most significant results of stellar astronomy, I believe.”

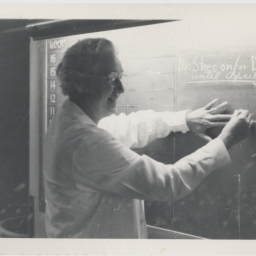

Figure 2. Leavitt working at the Harvard College Observatory.

By the time Shapley became Director of the HCO in 1921, Leavitt was Head of Stellar Photometry. Not long after, however, Leavitt fell ill with stomach cancer, passing away on 12 December that year at age 53.

More than three years after her death, Swedish mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler wrote to Leavitt at the Observatory, saying that hearing of her work “has impressed me so deeply that I feel seriously inclined to nominate you to the Nobel prize in physics for 1926.” As Nobels cannot be awarded posthumously, this was unfortunately not possible. Shapley, in a grotesque display, wrote back to Mittag-Leffler, essentially trying to claim credit for Leavitt’s work and accomplishments, presumably angling for the prominent man to nominate him instead (he did not). More than 20 years earlier, Mittag-Leffler had played a key role in ensuring that Marie Curie won her first Nobel in 1903, when the committee had initially only intended to recognize her husband, Pierre, for the work they did together. Mittag-Leffler alerted Pierre to this fact, and Pierre then wrote to the committee encouraging them to include Marie as well, resulting in her being the first woman to win a Nobel.

The Women of the Harvard College Observatory

As mentioned, the HCO holds a special place in women’s history as a hub of female scientists at a time when few such opportunities existed. In addition to Leavitt’s work, other groundbreaking achievements included:

-

The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra, published in 1890—Williamina Paton Fleming classified most of the spectra and was credited with classifying more than 10,000 featured stars and discovering 10 novae and more than 200 variable stars. The catalogue was funded by Mary Anna Draper in honor of her late husband, an amateur astronomer whom she worked with on astronomical photography and research in her own right. Florence Cushman determined the positions and magnitudes of the stars in the catalogue, which featured the spectra of around 222,000 stars. (Fleming did not have the educational and financial advantages of colleagues like Leavitt; she was Pickering’s maid, in addition to being a Scottish immigrant and single mother, when he recruited her to work at the HCO.)

-

Antonia Maury published her own stellar classification catalogue in 1897, which included 4,800 photographs and her analyses of 681 bright northern stars. It was the first time a woman was credited for an observatory publication.

-

From 1901 to 1912, Annie Jump Cannon devised the current Harvard classification system, the first real attempt to organize and classify stars based on their temperatures and spectral types. It is still in use today. Over her 40-year career, Cannon observed and classified more than 200,000 stars.

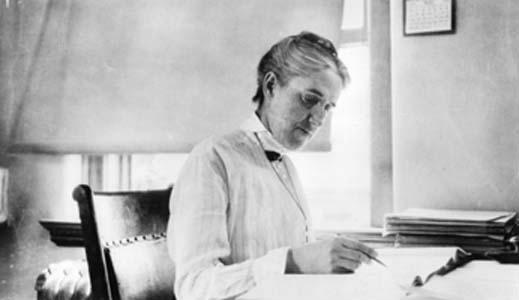

Figure 3. Leavitt (right) and fellow astronomer Annie Jump Cannon

Leavitt biographer Anna von Mertens and Dava Sobel, author of The Glass Universe, have observed that Pickering’s willingness to provide women with an entry into scientific roles was at the core of the HCO’s environment. “Pickering and Leavitt together, they wanted to move the field of astronomy forward…you can really see in the respect for each other—for one thing, Leavitt was able to publish her scientific papers under her own name, which is extraordinary for that time,” von Mertens has noted. “That group of support allowed individuals to shine so brightly.”

Legacy for Women and Girls Today

Leavitt’s work laid the foundation for measuring not only our galaxy, but others as well. Beyond this, however, she serves as a reminder that women have often been relegated to the “boring” tasks—the repetitive and perhaps seemingly less important duties that nevertheless have to be done. Yet in the sciences, this is often where discoveries are made. While we are hopefully past the days of such responsibilities being categorized as “women’s work,” they are still necessary and can still feel like drudgery. As Leavitt biographer Anna von Mertens noted, “When you create an experiment and replicate that, those are tedious steps and precision and care are required. So it’s just that we need to take the gender away and just recognize, ‘oh, this is what science is.’” Stories like Leavitt’s provide hope that the “boring” jobs can result in amazing discoveries that change how we see (and measure) the universe.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Document Analysis

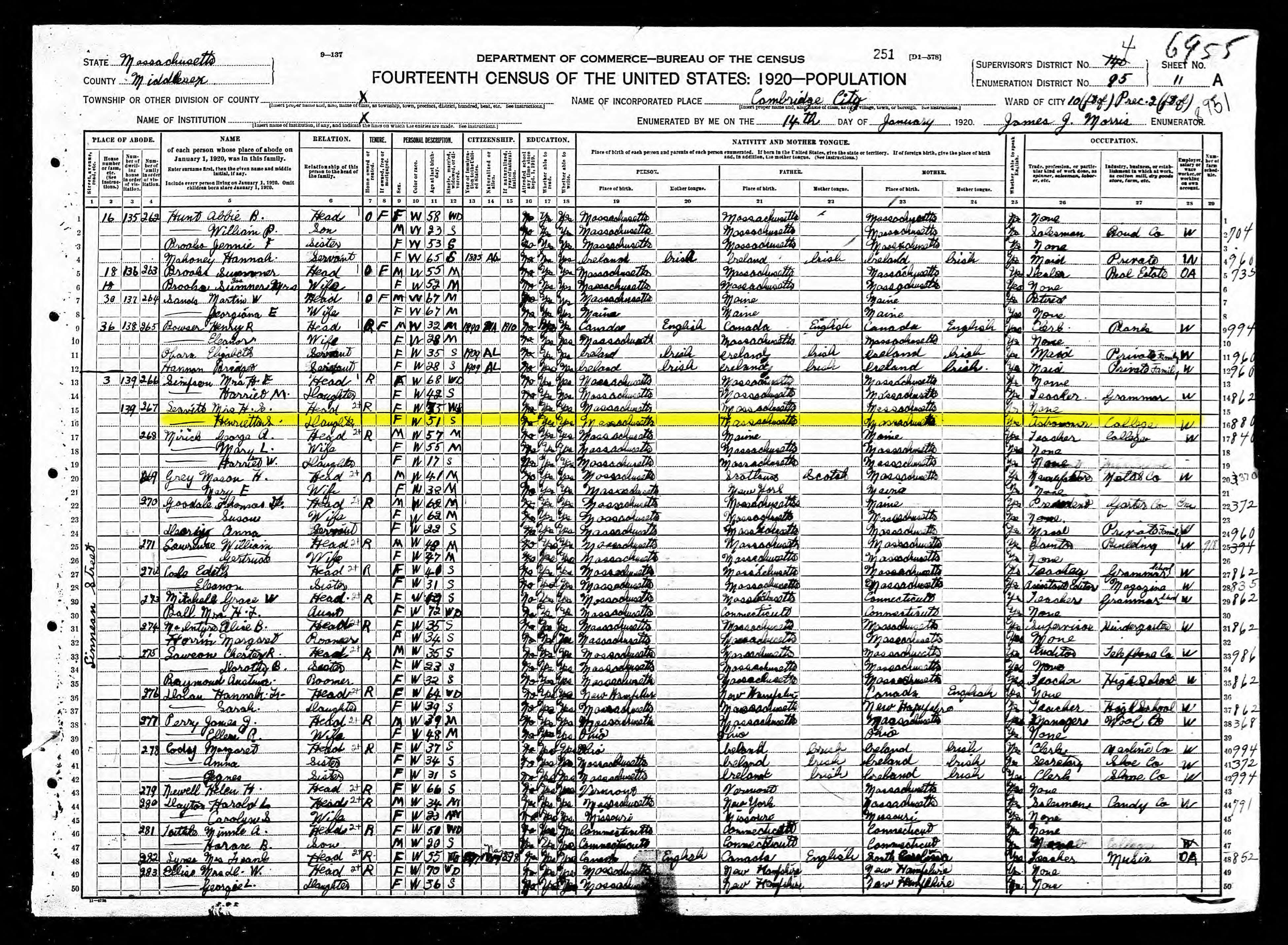

1920 US Census with Henrietta Leavitt's entry (highlighted) noting her occupation as an astronomer.

Observe

- Is there anything on the document you can read? What does it say?

- How is the information arranged on the page?

- What kind of document is this?

Reflect

- What is the purpose of this document?

- Who created this document?

- When looking at the answers from men versus women, what stands out? How does this help us understand common gender roles of the past?

- Why does Henrietta Leavitt's entry stand out?

Question

- What further questions does this document inspire?

- How can we use this document to understand the past?

J J O’Connor and E F Robertson, “Henrietta Swan Leavitt,” MacTutor (School of Mathematics and Statistics

University of St Andrews, Scotland), August 2017, https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Leavitt.

Emily A. Margolis and Samantha Thompson, “Remembering Astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt,” Center for Astrophysics, December 28 2021, https://www.cfa.harvard.edu/news/remembering-astronomer-henrietta-swan-leavitt

Anna von Mertens, Anna von Mertens on Henrietta Swan Leavitt, interview by Allison Tyra, Infinite Women podcast, June 16 2025.

Audio: https://creators.spotify.com/pod/show/infinite-women/episodes/Anna-von-Mertens-on-Henrietta-Swan-Leavitt-e306ho0/a-abr5sep

Transcript: https://www.infinite-women.com/wp-content/uploads/Anna-von-Mertens-on-Henrietta-Swan-Leavitt-transcript.pdf

Image citation: Henrietta Swan Leavitt at about 30 years of age. Popular Astronomy, v. 30, no. 4, April 1922. Courtesy Library of Congress, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2019/12/henriettaleavitt/

MLA — Tyra, Allison. “Henrietta Swan Leavitt” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago — Tyra, Allison. “Henrietta Swan Leavitt.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/Henrietta-Swan-Leavitt.

Anna von Mertens, Attention is Discovery: The Life and Legacy of Astronomer Henrietta Leavitt (The MIT Press, 2024).

Dava Sobel, The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars (Viking, 2016).

George Johnson, Miss Leavitt’s Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe (W.W. Norton, 2005).

Mae Jemison

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact history@womenshistory.org.