Mary Agnes Chase

Mary Agnes Chase advanced American botany through groundbreaking grass taxonomy, influential publications, and significant field research across the Americas.

She challenged gender discrimination in science and played an active role in major social movements, including women’s suffrage and racial justice advocacy.

Her legacy endures in modern STEM and civic education, inspiring efforts to diversify scientific fields and highlight the connections between inquiry, activism, and social change.

“It is such a heavenly place to stay it is hard to tear everything away,”

Mary Agnes Chase, Brazil Letters

Early Life

Mary Agnes Chase was the youngest of four children born to Mary Elizabeth Cassidy Meara and William Ingraham Meara, an Irish immigrant who worked first as a railroad laborer and later as a farmer (Natural History Museum, n.d.). The Meara family lived in poverty on their farm in Onarga Township until 1871, when William died, leaving two-year-old Mary Agnes and her siblings in their mother’s care (Garness, 2021). After her husband’s death, Mary’s mother moved the family from Onarga Township to Chicago, changing their last name from Meara to Merrill to avoid anti-Irish discrimination (Natural History Museum, n.d.).

Figure 1. A New York Times advert in 1854.

Beginnings of Agrostology

When Chase reached school age, she briefly attended a public grammar school in Chicago before becoming a typesetter and proofreader for the School Herald Newspaper to help support her mother and siblings. While working there, she met the editor William Chase and married him at age 19. Tragically, he passed away from tuberculosis less than a year later, leaving her a widow at age 20. Four years later, a visit to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago with her cousin Virginius Chase inspired her to start an independent study of northern Illinois flora (National History Museum, n.d.). Chase became interested in grasses, in particular, as she believed they were ‘what holds the world together’ (Henson, 2003). While composing her first field book, Chase took classes at the Lewis Institute and the University of Chicago (Zeldovich, 2019). Chase immersed herself in agrostology, and her skill in the field did not go unnoticed. While studying grasses in an Illinois swamp, Chase met Reverend Ellsworth Hill, who later became her mentor and introduced her to Charles Frederick Millspaugh. The two men recruited Chase to illustrate their publications Plantae Utowanae (1900) and Plantae Yucatanae (1903–1904). Chase also worked as an illustrator for Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. She completed both projects entirely as a volunteer, a strategy many women used at the time to enter botany despite gender discrimination, since botanical illustration was viewed as a fine art rather than a scientific discipline (Horne, 2016).

Figure 2. Sample illustration from The First Book of Grasses, Mary Agnes-Chase (1922, p.12).

Illustrator to Scientific Assistant

Chase’s extensive volunteer work as an illustrator showcased both her artistic precision and her growing scientific knowledge, which caught the attention of researchers and ultimately led to her first formal opportunity with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). In 1903, Chase took and passed the required USDA examination for botanical illustrators, which qualified her for appointment within the agency. The position required her to leave her home in Chicago and relocate to Washington, D.C. However, her time with the USDA was short-lived because she soon crossed paths with Albert Spear Hitchcock, who hired her as an illustrator at the National Herbarium (Horne, 2016). At the National Herbarium, Chase often stayed past working hours to study specimens, allowing her to develop a self-taught mastery of Poaceae (previously Gramineae) grass taxonomy (Horne, 2016). This taxonomy extended beyond lawn grasses and encompassed economically important plants such as grains and corn, making her published papers on the subject highly valuable to agricultural research institutions (Zeldovich, 2019). Hitchcock promoted Chase to Scientific Assistant in Systemic Agrostology at the National Herbarium in 1907, giving her the opportunity to pursue agrostology beyond botanical illustration.

Figure 3. Photo taken by Chase or Hitchcock in their research in the Grand Canyon.

Chase and Hitchcock began collaborating on their botanical work, with Hitchcock noting that her “expertise was imperative to the research that was yet to come” in their effort to analyze all the grasses in the Americas (Zeldovich, 2019, para. 5). However, the project required significant funding, and the search for support revealed to Chase how deeply academia favored men. Hitchcock secured funding almost immediately, revealing to Chase the stark contrast between the support he received and the barriers she faced. In his request for funding their South American research, he wrote that he saw no reason a woman could not meet the demands of fieldwork (Zeldovich, 2019). Additionally, in 1911, the field research station in the Panama Canal they planned to use prohibited women from using the facility. This left Chase with little choice but to fund the expedition herself, and she did so with support from organizations in which she was an active member.

Beyond Agrostology

While Chase was pursuing her research in agrostology, she was very active in the social movements of her time. She was known for her strong commitment to social justice and her active participation in movements for social change. Chase was a member of several organizations, including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the Socialist Party. Her experiences with gender discrimination in the scientific community motivated her to become more active in the National Women’s Party and its public protests. One such event occurred when she joined her fellow suffragists in burning Woodrow Wilson’s speeches in front of the White House, an act that resulted in a ten-day jail sentence in 1915. While imprisoned, Chase joined other suffragists in a hunger strike. Two years later, authorities jailed Chase again for her role as one of the Silent Sentinels picketing the White House.

Figure 4. National Women’s Party watchfires outside of the White House.

The Brazil Expeditions

Chase did not secure the funds needed to continue her agrostology research in South America until 1924. She received help from women missionaries in Latin America, who hosted her in their homes and assisted with travel logistics. While in Brazil, she met botanist Doña Maria Bandeira, who conducted research at the Botanical Garden in Rio de Janeiro and the two became close friends. On her second trip, Chase and Bandeira climbed one of Brazil’s highest peaks, Mount Itatiaia. During her eight-month expedition, she identified five rare plant species and discovered eight new fungi species, including huitlacoche, which grows on corn (Zeldovich, 2019).

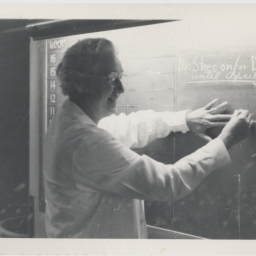

Figure 5. Chase collecting specimens on horseback in Brazil in 1929.

Her time in Brazil proved highly productive, leading to multiple research papers and her first book, The First Book of Grasses. Although she returned to the United States to continue her work for the USDA and the National Herbarium, she received more recognition from Brazilian botanists than from her colleagues at home (Zeldovich, 2019).

Legacy

Mary Agnes Chase’s legacy remains deeply embedded in American scientific, educational, and social landscapes. As one of the most influential agrostologists of the twentieth century, she developed taxonomic research on grasses that still underpins modern botanical science, agriculture, and environmental management. Her publications, field collections, and classification systems remain foundational resources for the USDA and botanists worldwide. Beyond science, Chase’s life reflects perseverance in the face of exclusion, and her activism in the women’s suffrage movement and her advocacy for racial and gender equality make her a model of civic courage. Today, her story inspires efforts to diversify STEM fields, uplift women in science, and recognize the interconnectedness of scientific inquiry and social justice.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Photo Analysis

1. Observe

What do you notice without interpreting?

2. Reflect

What clues in the photo help you understand its context or meaning?

3. Question / Wonder

What questions does this photo raise?

What specific research was Chase conducting during this expedition?

What challenges could she face as a woman scientist working in remote areas in the 1920s and 1930s?

Who accompanied her on these journeys, and what were their roles?

How did the specimens she collected influence scientific knowledge in the United States?

What does this image reveal about gender expectations in scientific exploration during her lifetime?

4. Historical Significance

Why does this primary source matter?

Bulik, M. (2015, September 8). “’1854’ — No Irish need apply” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/08/insider/1854-no-irish-need-apply.html

Natural History Museum. (n.d.). Chase, Mary Agnes (1869-1963). In Plants of the World Online. https://plants.jstor.org/stable/10.5555/al.ap.person.bm000001409

Garness, K. (2021, May 1). Botanist biographies: Mary Agnes Chase. Illinois Native Plant Society. https://www.illinoisplants.org/botanist-biographies-mary-agnes-chase/?doing_wp_cron=1762972494.5299360752105712890625

Henson, P. M. (2003). “What Holds the Earth Together”: Agnes Chase and American Agrostology. Journal of the History of Biology, 36(3), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIST.0000004568.11609.2d

Horne, S. (2016, June 16). Art is a science: Women illustrators breaking gender barriers and the story of Agnes Chase [Issue 21]. Lady Science. https://www.ladyscience.com/art-is-a-science-mary-agnes-chase/no21

Smith, J. P. (2018). Mary Agnes Chase. Botanical Studies, 81.

Smithsonian Institution Archives. (n.d.). Mary Agnes Chase Brazil letters, 1929-1930 [Collection finding aid]. https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/fbr_item_modsi89

Zeldovich, L. (2019, March 19). The woman agrostologist who held the earth together. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-woman-agrostologist-who-held-the-earth-together/

MLA — Cross-Harris, Katlynn. “Title” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago — Cross-Harris, Katlynn. “Title.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-agnes-chase.