Alice Ball

An American chemist who, at the age of 23, developed the only effective treatment for leprosy until antibiotics were developed in the 1940s.

Due to the groundbreaking nature of her discovery, she became the first woman and first African-American offered an instructor position in chemistry at the College of Hawai’i.

For decades, her contributions were erased from history when a male colleague, later the college’s president, claimed credit for her discoveries.

“I work and work and still it seems that I have done nothing.”

Dr. Alice A. Ball, a quote from her high-school yearbook

Early Life and Education

Born on July 24, 1892, in Seattle, Washington, Ball grew up in a middle-class African American family that valued education. Her father, James, was a lawyer and newspaper editor, and her mother, Laura Louise, was a photographer. Ball was first introduced to chemistry by way of her photographer grandfather’s darkroom. He, James Presley Ball Sr., was one of the first African Americans to learn the daguerreotype process and had captured portraits of famous nineteenth century figures like the abolitionist Frederick Douglass and writer Charles Dickens. This family environment of intellectual curiosity shaped Alice’s early interests in learning.

Ball’s brilliance emerged early in her life. She excelled in her studies at Seattle High School, where she was one of only a handful of Black students. Ball would later enroll at the University of Washington and earn two degrees, one in pharmaceutical chemistry (1912) and one in pharmacy (1914) (Gomes). She became the first Black woman to graduate from the University with a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry. Her undergraduate research centered on the chemical analysis of kava plants and, after graduation, she co-authored the paper, “Benzoylations in Ether Solution” that was published in the prestigious Journal of the American Chemical Society (U Washington).

Ball received a full scholarship to pursue graduate studies at the College of Hawai’i (now the University of Hawai’i) and she continued her study of the kava root, specifically its chemical properties and how to extract the active ingredients from the root. She became the first African-American woman to earn her master's degree at the College of Hawai’i (Jackson).

The “Ball Method”: A Medical Breakthrough

Her research gained the attention of Dr. Harry T. Hollman at the College of Hawai’i as well as Dr. Arthur Dean of Kalihi Hospital in Honolulu, both of whom were looking for treatments for Hansen’s disease (leprosy). At the time, the standard treatment for Hansen’s disease involved chaulmoogra oil. However, the oil was largely ineffective as it could not be properly absorbed by the human body when consumed orally and was too thick and painful when injected. Hollman wondered if Ball could extract the active ingredient from the chaulmoogra oil as she had done from the kava root (Gomes).

Figure 1

Scientific rendering of the Chaulmoogra tree.

With her sophisticated understanding of organic chemistry, Ball tackled the challenge. She made chaulmoogra oil effective by isolating the oil’s active compounds and modifying the chemical structure to make it suitable for injection. This technique, known as the “Ball Method”, isolated the ethyl esters of the fatty acids in the oil, allowing the treatment to be easily injected and absorbed by the body. It would be the first effective treatment for leprosy, alleviating symptoms and halting the disease’s progression. As Hollman wrote, “After a great deal of experimental work, Miss Ball solved the problem for me.” (The New York Times)

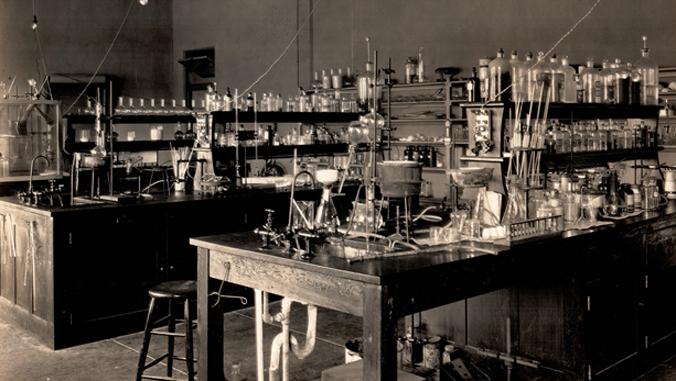

Figure 2

Alice Ball’s Lab at the University of Hawai’i.

Government-Sanctioned Leprosariums

For the first time in history, people with leprosy had hope for treatment rather than just isolation. Ball’s work promised to transform the lives of thousands of patients confined to leprosariums around the world, including those at the Kalaupapa settlement on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. Starting in 1866, the Kingdom's authorities forcibly removed more than 8,000 leprosy patients to this remote settlement and were legally pronounced dead (Senthillingham). If they had children during their confinement, they would be taken from the parents and adopted (NPS). Ball's discovery brought thousands back to life and back home.

Tragedy & Theft

In 1916, just one year after her discovery, Ball fell seriously ill. While the exact cause of her illness is unknown, some accounts suggest she may have been exposed to chlorine gas during her laboratory work. She died before she could complete her research and publish her findings. She was 24 years old.

Dr. Arthur Dean, the same man who initially reached out to Ball, published her research in his name in what some consider to be the most egregious cause of scientific credit theft in history (Ricks, Takara). He continued where she left off, refined her methods, and began publishing papers about the treatment without ever mentioning Ball’s foundational contributions. In fact, he presented this work as his own discovery—calling it the “Dean Method.” At the time, he was the dean of the college and would later become the president of the university.

For decades, Dean received accolades for developing the first effective leprosy treatment. Medical journals, textbooks, and historical accounts credited him with the breakthrough that Ball had actually achieved. The scientific community celebrated Dean as a medical pioneer while Ball’s name disappeared from the record entirely. This erasure was particularly tragic given the intersectional discrimination Ball faced as both an African American and a woman in early 20th-century science.

Legacy

Ball’s rightful place in scientific history was restored when Hawaiian historian, Kathyrn Takara, stumbled upon Ball’s original thesis (Takara). Further research revealed the extent of Ball’s pioneering research...and Dean’s theft of said research.

This discovery sparked efforts to restore Ball to her rightful place in history. The University of Hawai’i installed a plaque in her honor, established the Alice Ball Scholarship for those pursuing graduate degrees in chemistry, designated February 28th as Alice Augusta Ball Day, and dedicated a chaulmoogra tree to Ball’s honor.

Ball’s story illuminates the broader patterns of discrimination and erasure that marginalized scientists have faced throughout history (Takara). Her work saved thousands of lives and provided a crucial breakthrough in treating one of the most feared diseases of the early 20th century. The Ball Method remained the primary leprosy treatment until antibiotics were developed in the 1940s.

Her legacy serves as both an inspiration and a reminder: Ball’s brilliant mind and innovative research demonstrate the contributions that diverse perspectives bring to scientific advancement and, simultaneously, the theft of her credit underscores the importance of vigilance in ensuring that all scientists receive proper recognition for their work. In an era when we continue to grapple with representation and equity in STEM fields, Ball's story remains powerfully relevant, reminding us that groundbreaking discoveries can come from unexpected places and that justice delayed should not mean justice denied.

Ball was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2022 for her groundbreaking work.

Classroom Resources

Classroom Resources

Alice Ball and the Chaulmoogra Tree

Ask the students to read the text above and focus on the history of the Chaulmoogra tree using the following questions:

-

What is the scientific name of the chaulmoogra tree and where is it native to?

-

How was chaulmoogra oil traditionally used before Western scientific study began?

-

What part of the tree produces the oil used in medicine?

-

What role did global trade and colonial networks play in the spread and study of the chaulmoogra tree?

Alice Ball Day Ceremony at the University of Hawai’i

-

How does the dedication ceremony for Alice Augusta Ball communicate her legacy?

-

How does declaring a specific “Alice Augusta Ball” day elevate public awareness of her contributions?

-

How does Ball’s story speak to ongoing issues of recognition in science?

Lesson Plan

Primary Source Analysis

Primary Source Analysis

While we don’t have many primary sources for Alice Augusta Ball, we can analyze sources relevant to her legacy. Above is a photo celebrating the addition of a life-sized bust of Alice Ball in the Hamilton Library at the University of Hawai’i.

-

What message does the addition of Alice Ball’s bust send to the community of the University of Hawai’i and beyond?

-

How does this image portray the lasting legacy of Alice Ball?

Carry the Torch

Carry the Torch

Gomes, S. S. W., & Francisco Junior, W. E. (2024). Alice Ball: An African-American woman to foster education in chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 101(12), 5231-5239.

Jackson, M. M. (Ed.). (2004). They Followed the Trade Winds: African Americans in Hawaiʻi. University of Hawaii Press.

Lambert, M. M. (2024, March 20). A Young Black Scientist Discovered a Pivotal Leprosy Treatment in the 1920s — But an Older Colleague Took the Credit. The Conversation.

Mushtaq, S., & Wermager, P. (2023). Alice Augusta Ball: The African-American Chemist Who Pioneered the First Viable Treatment for Hansen's Disease. Clinics in Dermatology, 41(1), 147-158.

Ricks, Delthia (2023) Overlooked No More: Alice Ball, Chemist Who Created a Treatment for Leprosy. The New York Times.

Senthillingham, Meera (2015) Taken From Their Families: The Dark History of Hawaii's Leprosy Colony. CNN.

Swaby, Rachel. (2015) Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science--and The World. Broadway Books.

Takara, K. W. (2006). A View From the Academic Edge: One Black Woman Who is Dancing as Fast as She Can. Du Bois Review, 3(2), 335-350.

Wong, Kathleen M. (2022). The Trailblazing Black Woman Chemist Who Discovered a Treatment for Leprosy. Smithsonian Magazine.

MLA – Krichbaum, Emily. “Alice Ball” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago – Krichbaum, Emily. “Alice Ball.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/alice-ball