Virginia Apgar

Her largest accomplishment to medicine was the Apgar Score which she developed in the 1950s, revolutionizing newborn care with a standardized method to assess infant health immediately after birth.

Later in her career, she became a leading public health advocate, promoting maternal and infant health through education, outreach, and national policy efforts.

“True, I did not achieve everything for which I aimed, but these failures constitute probably less than 10% of the opportunities presented.”

Virginia Apgar quoted by L. Stanley James in Fond Memories of Virginia Apgar

Early Years and Education: Learning Voraciously

Virginia Apgar was born in Westfield, New Jersey on June 7, 1909, to Helen May Clarke and Charles Apgar. In 1909, an average of 27 out of every 100 people who died in the United States were children under the age of 5. 19 out of every 100 were under the age of 1 (US Census).

Figure 1

Virginia Apgar (age 8) and her brother Lawrence.

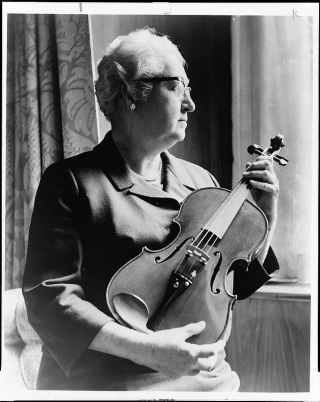

Virginia Apgar’s father, Charles, was an amateur inventor and astronomer. In 1904, her oldest brother, also named Charles, died before the age of 5 from tuberculosis. Her younger brother, Lawrence, suffered from chronic childhood illnesses. Her father’s interest in science as well as her brothers’ experiences with childhood illness shaped her early interactions with the medical field. As a child she also fostered and early interest in music, playing the violin, which she would continue to pursue for the rest of her life (W. Bamberger, 36).

In 1925, Apgar began studying at Mount Holyoke College as a zoology major (O’Dowd, 111). Her first letter home to her mother demonstrates the zeal for learning which would follow her throughout her lifetime:

“What we’ve done. They’ve kept us all so busy with lectures, etc that we’ve hardly had 10 minutes to ourselves. At 8:45 yesterday we went to the music building and were lectured at by Miss Woolley on the subject of Mary Lyon. Very good. At about 10, we went to the auditorium and were given an English vocabulary test... I ABSOLUTELY can’t write another word except that I’m very well and happy but I haven’t one minute even to breathe... I’m on my way to the music building to hear the Dean. Loads of love to all. I received the typewriting paper, envelopes and journal. I can never thank you enough for them. Good-night. Jimmy—that's what they’re calling me.” (Five College Compass)

Figure 2

Apgar (front left) with other members of the orchestra at Mount Holyoke College.

Carving a New Place in Medicine

Apgar graduated in 1929 and was soon accepted to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. Apgar was just one of 9 women in her class of 90 students. In 1933, when Apgar finished medical school, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression and Apgar had accrued over $4,000 in student debt (nearly $76,000 in 2025) (M. O’Dowd, 112, S. Borden, 51). Apgar experienced substantial financial hardship in the early years of her career, which may have driven her to pursue anesthesia instead of surgery. Anesthesiology was a relatively new medical practice that had its origins in nursing and was therefore more accepting of early women practitioners. (M. O’ Dowd, 112). Anesthesia was a neglected discipline when Apgar entered into it, and she saw the need for improvements especially for obstetric patients and newborn babies (V. Jay, 292–4).

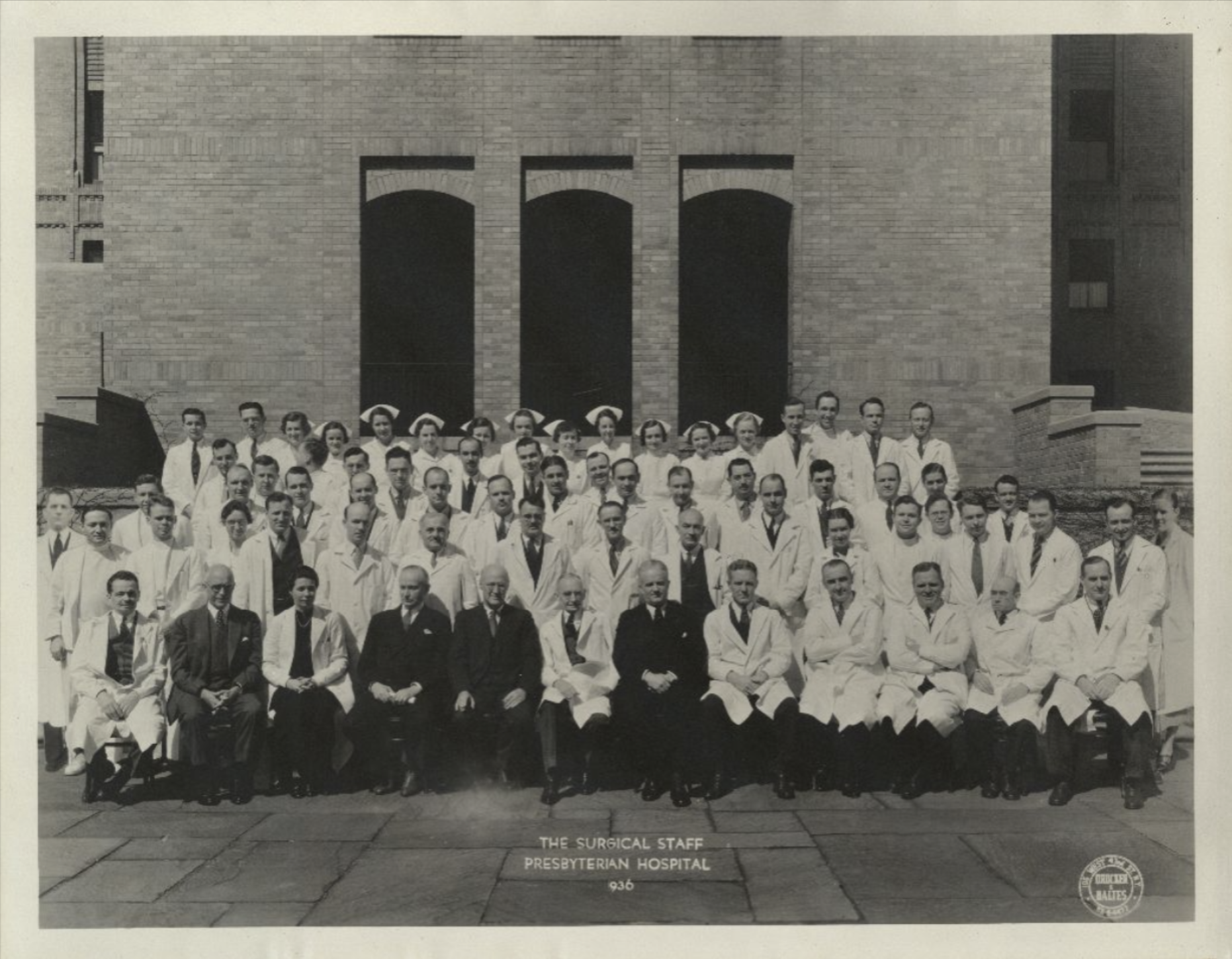

Figure 3

Surgical staff at Presbyterian Hospital. Apgar is depicted in the second row, third from the left.

Apgar held residencies at the University of Wisconsin under her later life-long mentor Dr. Richard Waters and at Bellevue Hospital in New York City in 1935-1937 (S. Borden, 49-53, “Virginia Apgar,” Britannica Academic). While she was privileged to receive the support in her early career, when she arrived in Madison, Wisconsin, for her training under Dr. Waters, she was surprised to find that she was the only female trainee and there was therefore no housing for her. She slept in Waters’ office for two weeks before being moved to the maids’ quarters.

Figure 4

Virginia Apgar at time of residency at the University of Wisconsin.

Pitfalls and points of confusion did not slow Apgar down. From 1938 onwards she was the director of the new department of anesthesiology at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center (V. Jay, 292-4). Apgar faced self-doubt with the fast incline of her career in an unprecedented field. She was especially nervous about this sudden responsibility so soon after completing her training, as she lamented to her mentor Waters in February 1938:

“By the second week I was ready to turn to law, to dressmaking, anything but anesthesia. After making numerous mistakes I remembered you had cautioned me against most of them, but somehow you must learn by making them yourself.”

Figure 5

Apgar (front row center) as director of the anesthesiology division at Columbia-Presbyterian.

Still, Apgar stood strong in trusting her own professional judgment, even when faced with conflict and condescension as described in this letter to Waters:

“One must allow time to defend one's choice of anesthetic with the medical consultant who accompanied the patient to the operating room thereby holding up the operation one half hour and making the surgeon furious—but the medical man had never heard of cyclo! Ah me!”

In 1949, she became the first professor of anesthesiology at the Columbia, and with this position she was the first female full-rank professor there. She was a contentious manager and teacher, and her former students frequently remarked on the quality and empathetic nature of her feedback (L. James, 2-3).

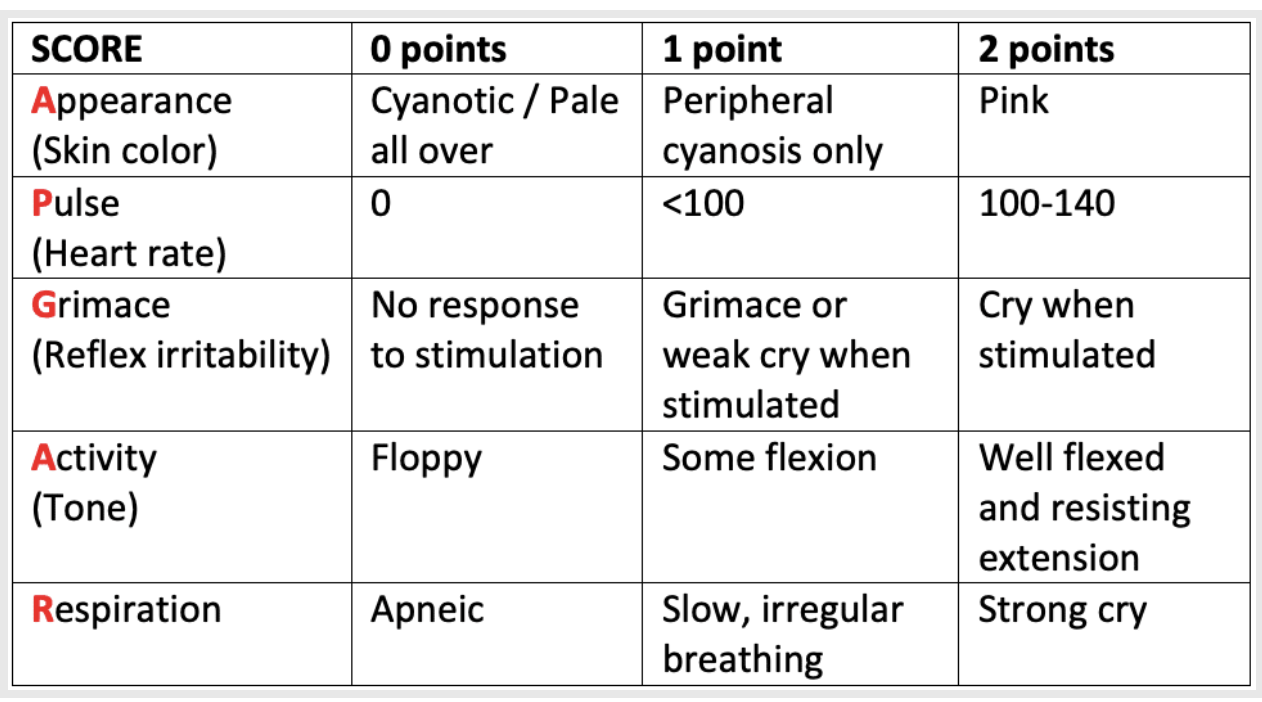

The Apgar Test

In the early 1950s, Apgar began formulating what would become known as the Apgar Test. Before this test, there was no systemized way to assess newborn infant’s health following birth and determine any potential need for immediate treatment. There was also no data collected across the United States to determine the conditions surrounding child or maternal mortality, limiting options for the development of better medical practice that would save hundreds of thousands of lives.

Apgar developed a simple system for evaluating the condition of newly delivered infants based on her experience as both a surgeon and an aesthetician. According to the test, five simple observations were to be made by delivery room attendants such as nurses, midwives, or doctors of the infant within one minute of birth.

Figure 6

The infant should be scored on a scale from 1–10, and the test can be repeated periodically depending on the score. Apgar tested this strategy for scoring newborns over the course of three years and in 1952 she published it under the title ‘A Proposal for a New Method in the Evaluation of the Newborn Infant” (L. Bowen, “Apgar Score”). Apgar herself did not give the test her own name through an epigram, but when she discovered from Dr. Joseph Butterfield at Colorado University that he and his residents referred to it through the letters A P G A and R, she was shocked and delighted.

“My Dear Doctor Butterfield:

I chortled aloud when I saw the epigram. It is very clever and certainly original. You might like to hear the greeting I received at Boston Lying-In one day by a secretary, who said “I didn’t know Apgar was a person, I thought it was just a thing.”

The creation of the Apgar Test was and continues to be considered Apgar’s greatest contribution to medicine which provides medical professionals a standardized means through which they can assess and treat newborn infants immediately following birth (M. O’Dowd, 109). However, Apgar herself was surprised at the many attempts to correlate Apgar scores to further developmental concerns and cautioned doctors against making such leaps without substantial research. As she wrote to R.S. Ikonen, who had sent her his doctoral thesis regarding the Apgar Score in 1974:

“It interests me to read how often the scoring system is expected to forecast conditions for which it was never intended... Actually, it’s uses were: 1) to predict infant mortality and 2) to point out to the physician the need for active resuscitation if the total score was four or less.

Now, 22 years later, the score is being examined for association with I.Q at school age, behavioral disorders, fatal infant diseases such as Tay-Sachs, autism, and length of time in the intensive care unit! I would not expect that there would be either a positive or negative association with these parameters. However, it does no harm at all to investigate under what conditions the score is useful or useless.”

Such instances demonstrate her dedication to honesty, integrity, and public access to accurate medical information that she pursued throughout her career as a doctor and would shape her later advocacy and public health work.

Public Health and March of Dimes: Constant Advocacy

In 1959, Apgar left Columbia to pursue a degree in Public Health from John Hopkins University. Before even completing her studies, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, now called the March of Dimes, offered her the opportunity to apply her new skills as the chief of the Division of Congenital Malformations. As part of this role, she toured the country to give talks and spread sound information to expectant mothers. She appeared on television and radio shows, authored columns in local newspapers, and spoke to audiences of any size (Foundation for Economic Education, “Virginia Apgar”). During this point in her career, she also authored the book Is My Baby All Right? Her personal approach was much to the benefit of her audiences, and she frequently responded personally to inquiries from women around the country with empathic approaches and medical advice.

Figure 7

Virginia Apgar appearing on Los Angeles station KLAC, 1964.

Apgar’s final professional achievement was in her work to create the first Committee on Perinatal Health which would incorporate relevant organizations such as the American Medical Association, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the March of Dimes, to improve maternal health and further limit infant mortality. Unfortunately, she did not live to see the official report from this committee as she died of complications due to liver failure in 1974 at Columbia’s New York Presbyterian Hospital (A. Ray, 4). In many ways, Apgar was lucky to live to achieve what she did, and in doing so to save upwards of millions of lives through her innovative work in neonatal care and public health. Through her empathy, her intelligence, her determination and drive, she responded to the needs of her time and transformed medicine.

Apgar received numerous awards during her lifetime, including the Ladies’ Home Journal naming her Woman of the Year in 1973 (“Virginia Apgar,” Britannica Academic). In 1961, Harold Patterson, a New Jersey orchid cultivator named a new breed of orchid after her. Apgar, an avid gardener, was thrilled.

Figures 8 & 9

Apgar receiving the Women of the Year Award from Ladies’ Home Journal in 1973.

Apgar was a lifelong learner, and she never stopped striving to achieve her best. She was an avid musician, even learning to create her own instruments. She was apparently an extremely competitive tennis player (L. James, 4). In the last years of her life, she started taking flying lessons, which she sought to master as she wrote to Robert Shakey in 1970:

“I seem to have the bad habit of wanting to see where the wheels are going to touch down, which means a direct nose dive on to the runway!! I am working to overcome this deficiency!”

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

-

How can you use this source to understand the rate of child mortality in the US in 1909?

-

Do the statistics differ in different areas or under different circumstances?

-

What does the rate of child mortality tell you about life in the US in 1909?

-

Compare these statistics to the rates of child mortality today. How have they changed? What causes can you infer have contributed positively towards this change?

2. Letter from Dr. Apgar to her daughter, Helena Apgar

-

What emotions do you notice in this letter from Virginia Apgar to her mother? Have you ever related to these feelings before?

-

What words and phrases are unfamiliar to you, that may be slang from the time? Can you use context clues to help understand their meaning?

-

What do you think about the subjects and activities Apgar discusses in her letter? Do they sound familiar, or interesting to you?

-

How is Dr. Apgar depicted in this photo?

-

What do you notice about her expression, what she is holding, and how the camera is framing her?

Carry the Torch

Carry the Torch

Bamberger, Werner. “Dr. Virginia Apgar Dies at 65; Devised Health Test for Infants: Named Vice President Professor at Columbia.” New York Times, Aug 08, 1974, 36.

Borden, Shelley B., Bradley J. Maerz, Douglas R. Bacon, “The Rock of Gibraltar: The Value of Mentorship in the Early Years (Dr. Virginia Apgar and Dr. Ralph Waters),” Journal of Anesthesia History, Volume 6, Issue 2, 2020, 49-53.

Bowen, Lowri and Mike Cadogan. “Apgar Score.” Life in the Fastlane. Jan 8, 2022. https://litfl.com/apgar-score/

Butterfield, P. M. “Foundations of pediatrics: Virginia Apgar (1909-1974)” Adv Pediatr, 59 (2012), pp. 1-7

Correspondence, 1925. Virginia Apgar papers, MS 0504. Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections. https://aspace.fivecolleges.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/1928 Accessed May 15, 2025.

Foundation For Economic Education and FEEGA. “Virginia Apgar: The American Anesthesiologist Whose Medical Test Saved Millions of Newborns.” CE Think Tank Newswire, Aug 18, 2019

James, L. Stanley. “Fond memories of Virginia Apgar.” Pediatrics January 1975; 55 (1): 1–4.

Jay, V. On a Historical Note: Dr. Virginia Apgar. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 1999;2(3): 292-294.

O’Dowd, Mary E., and Colleen Blake. “Virginia Apgar: Focusing on Prevention, She Structurally Transformed Maternal and Child Health for Generations.” In Junctures in Women’s Leadership: Health Care and Public Health, edited by Mary E. O’Dowd and Ruth Charbonneau, 109–30. Rutgers University Press, 2021.

Ray, Andrew R., Daniel Haines, and Ryan Grell. “Virginia Apgar (1909-1974): The Mother of Neonatal Resuscitation.” Cureus 16, no. 5 (2024): 1-5.

“Apgar, Virginia.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2020.

MLA — McKelvie, Lydia. “Virginia Apgar.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago — McKelvie, Lydia. “Virginia Apgar.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/virginia-apgar.

Apgar V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1953; 32(4): 260–7.

Apgar V. Infant Resuscitation. Postgrad Med. 1956 May;19(5):447–50

Apgar V, Holaday DA, James LS, et al. Evaluation of the newborn infant; second report. J Am Med Assoc. 1958 Dec 13;168(15):1985–8

Apgar V. The newborn (Apgar) scoring system. Reflections and advice. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1966; 13(3): 645–50.