Feminism on the Flat Track

The hiss of skates on a glossy track mixes with the cacophony of yells and cheers from a crowd fueled by fervor and local brews. An announcer hollers into a microphone, keeping score while simultaneously rattling off names like Punky Bruiser and Gail Gaunlet. On the track, a group of women with mouth guards, ripped fishnets, and apple sized bruises barrel into each other, grunting and yelling as they throw elbows and insults. One woman with a star on her helmet jumps over tangled legs, whizzing by the screaming crowd to win her team as many points as she can.

This is roller derby.

In the early 2000s, roller derby witnessed a revival, quickly becoming a popular sporting event and past time. Yet roller derby’s history stretches back to over a century ago. A six-day skating marathon took place in Madison Square Garden in the mid-1880s. In six days, William Donovan emerged the winner, skating over 1,000 miles, only to die of exhaustion one week later. The surprise of Donovan’s death, whose victory was publicized in various newspapers, shocked the public. Anger and fear over the sport’s apparent danger and deadly consequence quickly turned the popularity of roller skating into an unpopular past-time.

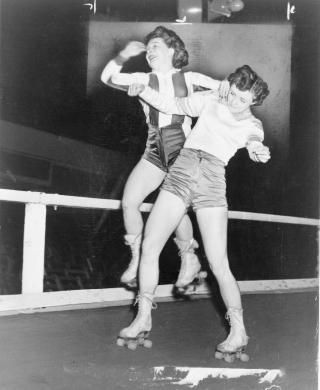

Roller Derby March 1950

Almost exactly fifty years later, a Leo Seltzer created what we today know as roller derby. Arguably a feminist, Seltzer realized that sports demographics were missing female participation and interest. In 1935, Seltzer introduced his version of marathon skating, or roller derby, to the public at the Chicago Coliseum. He managed to entice hundreds of women from across the United States with a chance to compete and win his Transcontinental Roller Derby. The “Roller Derby” quickly transformed into an endurance race on a flat track to a banked oval track to increase the intensity and difficulty. To add flair to the long endurance bouts, skaters would sporadically start a “jam,” or sprinting races, encouraged by both the crowd and Seltzer. Jams quickly became physical, including brawls, even for the female players. The skater who won the bout by finishing as many laps as possible was given a cash reward and gained local fame.

Soon male and female competitors were combining insane feats of acrobatics, stunts, and skills. As roller derby reached increasing popularity, a popular sportswriter Damon Runyon, convinced Seltzer to change the rules of the co-ed sport to include more contact than just the quick and dirty jams. Runyon noticed that polite audiences grew wild with excitement once women and men began their jams. By 1939 and with the help of Runyon, Seltzer created four teams, with two five-person teams lapping each other, scoring points as they completed bouts. By putting more bodies on the track with a score system, violence quickly became the norm.

Roller Derby May 1950

For the next seven years, Seltzer and his teams played roller derby matches across the United States. It wasn’t until November of 1948, however, that New York television first broadcast a roller derby match. That same year, Seltzer formed the National Roller Derby League, consisting of six teams. Playoffs for the first National Roller Derby League even sold out at Madison Square Garden.

Roller derby continued in popularity until the late 1960s, when, despite broadcasting games on several networks, interest and popularity declined. But derby remained a staple in many towns, simultaneously representing blue-collar life and Depression-era realities of economics and societal restrictions. Derby faded away to local matches and Friday night entertainment until 1989 when RollerGames debuted on television. RollerGames was far from the original derby of the 1920s and 1930s. The show included a figure-8 track, banked only on one side with obstacles often placed in players’ way. The season long series even had a pit full of alligators in the middle of the track. The winner was declared if a skater could skate around the pit five times or throw their opponent into the alligator pit. Teams included famous female and male skaters from the 1960s and 1970s, including the “T-Bird Twins” from the renowned Los Angeles T-Birds, “Monster Man” Bernie Jackson, and “Skinney Minnie” Gwen Miller. Yet controversy, including rape allegations, and public disinterest forced production to cease after one season.

In 1999, The Nashville Network (now Paramount Network) debuted another made-for-television derby show named RollerJam. Unlike RollerGames, RollerJam used the same rules and banked oval track as classic roller derby. The one difference was that RollerJam players wore inline skates, not the traditional quad skates of previous decades. RollerJam included fictional storylines, like professional wrestling, and were featured more often than competitive skating itself. In 2001 RollerJam ended, but the roller derby revival was just beginning.

Roller Derby game between the Cherry Bombs (Green) vs Rhinestone Cowgirls (Red) on Aug 27, 2011, in Austin, Texas.

In Austin, Texas in early 2001, contemporary roller derby was born in a bar called Casino El Camino. “Devil Dan” Policarpo put out flyers all around town, calling for any women interested in beginning a derby team to meet for drinks and discuss the beginning of a new derby era. Once a group of women arrived at the Casino El Camino, Devil Dan pitched his idea for a girls-only league. Four teams emerged that night: the Putas del Fuego, the Hellcats, the Holy Rollers, and the Rhinestone Cowgirls. The rules were simple: a team of five (four blockers and one jammer) play two thirty-minute periods. Skating counterclockwise on a track, points were scored only by the team’s jammer, who breaks from the pack to circle the blockers of the other team desperately trying to take down the jammer. Body contact was encouraged.

Unfortunately, within the next few months and as soon as training began, gearing up for Austin’s first bout, Devil Dan emerged empty handed with no money to fund the four teams. The teams, increasingly distrustful of Devil Dan, forced him to leave shortly after, leaving the derby hopefuls struggling to find a coherent training strategy. Many of the women were looking to the well-known derby girls of the past to form their knowledge, and training was off to a rough start. But more teams began forming despite the fallout from Devil Dan, and soon two new leagues formed: Bad Girl, Good Woman Productions and the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association.

By 2006, roller derby boomed to over 135 leagues throughout the US, and today there are over 2,000 amateur leagues worldwide, including Yokosuka Naval Base’s Sushi Rollers, who compete across Japan and train in the base gym. Most of these leagues were, and are, amateur and self-organized. They are also run and owned by women. Such a phenomenon in the athletic world is rare but harkens back to the first female skaters of the 1920s and 1930s who were brave enough to compete alongside men.

Roller derby is often seen as a feminist sport, pushing against various stereotypes of womanhood and traditional femininity. Women who skated back in first half of the 21st century were often criticized for changing and ignoring traditional feminine roles, such as homemaker, mother, and wife. Additionally, engaging in violence, as well as actively participating in sport, was often seen as immoral.

Two blockers from FoCo Girls Gone Derby (white) attempt to ward off the Pacific Roller Derby jammer (black) at the 2011 Dust Devil tournament.

Yet today’s roller derby often pulls away from traditional womanhood and femininity by using a DIY, punk aesthetic. Encouraged to use homemade uniforms, fake names referencing bands, pop culture, or humor, and the use of heavy makeup and fishnets are a homage to the punk scene of the late 1970s. Often third-wave feminism had an influence on the independence and aggressiveness of these all-women leagues, and quickly became a home for the LGBTQ community to find a safe and welcoming place. Since most leagues and teams were formed by stay at home mothers, lawyers, teachers, and physicians, as well as younger college students and “misfits,” roller derby quickly became an avenue for expression for women everywhere.

In 2009, the film Whip It, based on a short novel by Shauna Cross, created awareness and even more popularity for the sport. Shortly after, interest in filming roller derby to showcase in small documentaries increased and diversified the fan base from local public bouts to large stadium audiences.

Roller derby, despite its somewhat muddled history that often included assault accusations, social criticism, and wavering interest, has nonetheless allowed women of all shapes, sizes, and identities to find a community that values sportsmanship in skill and aggression. The powerful portrayal of a group of women in spandex, glitter, fishnets, and mouth guards challenges gender roles and stereotypes of women in sports. While there are some male only derby leagues, most teams are comprised of and run solely by women, who embrace the ability to rid themselves of pent up frustration on the track and show the world what it means to hit like a girl.