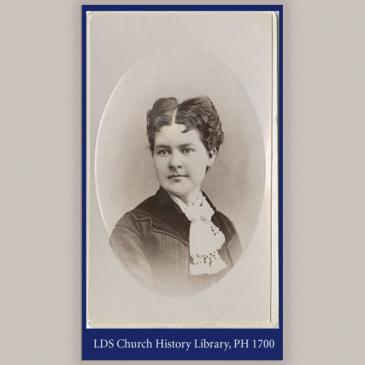

Jeannette Rankin

Throughout her six-decade-long career as a lawmaker, lobbyist, activist, and citizen, Jeannette championed women’s rights, workers’ rights, peace, and democracy.

An unwavering pacifist, Jeannette was the only congressperson to vote against both WWI as well as WWII and in 1968, considered running for a third term in opposition to the Vietnam War.

“Just having the vote is not all that is required if we are to have a voice in government. We must have the political machinery by which the votes may be cast.”

Jeannette Rankin

Early Years: An Education in Democracy

Born on a ranch outside Missoula, Montana, in the summer of 1880 to John and Olive Rankin, Jeannette grew up in a community where both gender roles and class mobility were far more flexible than they were on the East Coast or Europe. On Montana’s rural homesteads and ranches, survival required every set of hands, regardless of gender. Jeannette spent many summer days corralling the horses and helping to raise the neighbor’s barns. Meanwhile, the men had no compunction about helping to deliver a baby or tending the kitchen gardens.

This reality shaped a childhood steeped in practical equality and mutual dependence. As Rankin later told her audience, “The courage it took to face the privations inherent to this hardscrabble life has brought the men and [women] close together in the working out of a better world.”

But more than many in this community, Rankin came from a place of privilege, though this, too, was born from Montana’s nearly unique class mobility. Her father, John, had come to Missoula as a failed miner but taught himself the fundamentals of engineering and parlayed his success as a bridge builder into a vast real estate empire in Missoula. His wife, Olive, and Rankin, his oldest daughter, played integral roles in the family’s upward mobility. Rankin, in particular, became her father’s protégé and right-hand woman.

Rankin also grew up with a profound awareness of the devastating toll westward expansion took on Indigenous communities. Even as a child, she grasped the injustice of the prolonged war waged by white settlers, her people, against the Native Nations who had stewarded the land for generations. This early recognition of moral contradiction laid the foundation for Rankin’s lifelong commitment to peace.

Blazing A Path In Social Reform

That clarity extended to her views on education and social reform. The first in her family to attend college, she earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Montana. But she found her true education in Boston while visiting her brother, Wellington, at Harvard, where she often walked through the city’s tenements. Here, the cruelty of poverty, child labor, and industrial exploitation were laid bare in the faces of those who scratched out a living in factories and sweatshops.

The experience sent Rankin on a lifelong quest to find the means to create systemic change. She made her first stop at a job at the Telegraph Hill Settlement House in San Francisco. Though modeled after Jane Addams’ transformative Hull House, Rankin still felt that nothing short of government intervention would be required to cure the ills of poverty that affected those they served and the millions like them across America’s cities.

In 1908, Rankin applied and was accepted to the New York School of Philanthropy, where they studied under such luminaries as National Consumers League co-founder and General Secretary Florence Kelley, soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Judge Louis Brandeis, and Civil Rights leader Booker T. Washington. But it was at the night court where she was helping convicted sex workers find a second chance, where Rankin was introduced to the women’s right to vote through her supervisor, a court clerk by night and a Suffragist by day. The idea that her voice, and the voices of all women, might one day be included in We The People struck Rankin like lightning.

After earning her Master’s degree, Jeannette distinguished herself in the successful campaign for Women’s Suffrage in Washington State. Taking note of her tenacity, Harriet Laidlaw, one of the prominent patrons of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), donated her salary so that Jeannette could join as Field Secretary. Over the next few months, Rankin barnstormed the nation, traveling to over a dozen states, campaigning for women’s right to vote and most notably, helping to win it in California.

Yet all along, her home state called her back.

On The Campaign Trail to History

In 1911, Rankin began a campaign for Women’s Suffrage in Montana. Rather than envisioning herself as the sole star of Suffrage in Montana, Jeannette charted a constellation of women activists throughout Big Sky Country, each of whom was empowered to organize her community independently as she saw fit. This truly grassroots form of organizing flipped both State Houses in favor of the women’s right to vote, and the measure to put Women’s Suffrage on the ballot in 1914 passed with an overwhelming majority.

Once more, on the campaign trail, Jeannette reactivated this powerful network of women activists who successfully saw suffrage through that November in the popular vote.[1]

While adding another state to the side of Women’s Enfranchisement was an accomplishment enough for a lifetime, Rankin was far from finished. Indeed, she set her sights on a goal that no woman had ever come close to achieving: A seat in Congress.

In July 1916, Rankin launched her historic campaign, which took her across the length and breadth of Montana in trains, borrowed cars, and on horseback when necessary, speaking to miners, ranchers, farmers, office workers, men, and newly enfranchised women from all walks of life. But more than speaking, she listened. From their aspirations, desires, and dreams, she constructed a platform of women’s rights, pacifism, labor reform, and, above all, democratic reform.

In addition to her tenacity and political acumen, Rankin had another ace up her sleeve. At the time, Montana was an “open state” with two Congressional seats, meaning every eligible citizen could vote for both of their representatives. Freed from zero-sum elections that disadvantaged women then as much as they do now, Rankin ran on the slogan, “Vote for your local man and Jeannette Rankin.”

A friend to all, an enemy of none, Rankin operated her campaign on the bedrock of civility, decency, and democracy. The voters of Montana flocked to her vision built from their collective voices and catapulted her into Congress with a resounding victory.

The Gathering Storm

Just months later, on March 2, 1917, Congresswoman-elect Rankin stood before a crowd of 3,000 at Carnegie Hall. Her election had drawn national headlines, and now she stood on the brink of history once more, about to take her seat in the House of Representatives. Yet her appearance came at a perilous time. The United States stood on the brink of entering World War I. Government and corporate propaganda had shifted public opinion toward war, and many suffragists, including NAWSA President Carrie Chapman Catt, supported it, believing it would help women win the vote. Rankin, an avowed pacifist, refused to compromise her ideals.

The crowd hushed as reporters poised their pencils. Rankin looked into the audience with her smiling gray eyes and began. But rather than talk about war and peace, as perhaps many had expected, she spoke of democracy.

She condemned the corporate greed and imperialist ambitions that had pushed the world into war for nothing more than money. But she did not give in to despair.

“In groping around for some way out of our difficulties, we are conscious of a new spirit in the world,” she said, her voice lifting, “We are beginning to feel that the people, all of the people working together, constitute our only hope.”

She began with women’s enfranchisement. But she didn’t stop there.

“Just having the vote is not all that is required if we are to have a voice in government,” she said. “We must have the political machinery by which the votes may be cast.”

She advocated for expanding Montana’s absentee voting law nationwide and proposed that all states adopt Montana’s Corrupt Practices Act, which banned corporate spending in elections. Next, she supported the direct election of presidents to ensure equal weight for every vote and open primaries, allowing any voter to select their preferred candidate regardless of party affiliation. Drawing from her own experience, she urged the use of multiple-member congressional districts and ranked-choice voting, systems that, then as now, increase representation and reduce partisanship.[1]

As applause erupted, it must have seemed to Jeannette that a broader vision of We the People was within reach.

Yet even her prodigious strength could not derail the freight train of global conflict rushing headlong through America’s political landscape. On April 2, 1917, Rankin’s first day in Congress, President Woodrow Wilson called for war. Unflinchingly committed to peace, Rankin stood when her name was called.

“I want to stand by my country,” she said, her voice ringing out. “But I cannot vote for war. “I vote no.”

The Interwar Years

Decades before President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned of the military-industrial complex, Rankin saw its dangers and knew intrinsically that “The War to End All Wars” was just the beginning if society did not change.

From 1919 to 1939, Rankin worked tirelessly, often to the point of personal impoverishment, on the cause of disarmament with numerous organizations, including the Women’s Peace Union, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and, most significantly, the National Council for the Prevention of War. It was during this time that she coined her famous phrase, “You can no more win a war than you can an earthquake.”

As in her days on the suffrage campaign trail, Jeannette traversed the nation in cars and trains in the name of peace. She also lobbied Congress to curb military spending and the expansion of the Navy, especially the construction of battleships, which, she correctly predicted, would push the nature of war past the point of return.

In 1939, Rankin decided to run for Congress once more on a platform of peace and democracy. As she told her audiences, “The way to stop Hitler is by democracy. We must use constant pressure on Congress not to do the easy thing, but to do the right thing… Hate is one of the most vicious things in the world… The way to help Germany is to help them, through democracy, to get rid of their leader.”

Yet, by then, it was too late. But Rankin too had crossed her own Rubicon of ethics and could find no way back.

She won her seat and did everything she could in Congress to help both America and Germany expand their democracy to fight the threat of fascism both at home and abroad. But in the Pacific Ocean, war brewed beyond the horizon of even her vision, and on December 7, 1941, the Japanese Imperial Army attacked Pearl Harbor. The attack caught her and the nation by surprise.

Yet she had spent the better part of her lifetime warning of the inevitability of war when the whole world was building war machines and worked tirelessly to dismantle these weapons of destruction with everything she had. However futile, Congresswoman Rankin could not now bring herself to vote for that thing she so abhorred and spent her life working against. She voted no once more, but this time as the sole dissenting voice.[1]

A New Day

After her term in Congress, Rankin essentially retired from public life. She spent months at a time in India, studying the non-violent independence movement founded by Mahatma Gandhi and traveling the world, learning about its people and cultures. But in 1965, when President Lydon B. Johnson sent the first US combat troops to Vietnam, Jeannette could remain silent no longer and became one of America’s earliest and most outspoken critics of the war.

Near the end of her life, while still working for peace, Jeannette returned to the ideals she had evinced that night on stage at Carnegie Hall. She began writing lawmakers and notable personalities alike about the promise of ranked-choice voting, multimember districts, and the direct election of presidents. In 1971, she even appeared on The Merv Griffin Show, with an audience much larger than that of 1917. She spoke with a crackling voice of old age yet with no less clarity in thought about truly representative American democracy. Though few heeded her voice then, the reforms she advocated for continue to live on in today’s political discourse

Jeannette Rankin passed away on May 18, 1972, in Carmel, California.

In her final years, Jeannette Rankin was often remembered for her votes against war. But her true legacy runs deeper: she was a lifelong defender of democracy, not just the right to vote, but the right to have that vote count, to shape the system, and to live free from exploitation and violence.

Classroom Resources

Classroom Resources

Primary Source Analysis

-

Speech Analysis: “Woman Suffrage” (1918)

-

Resource: Excerpt from Rankin’s January 10, 1918 speech in Congress.

-

Activity: Analyze how Rankin frames democracy and equality. Compare her ideas with those in the Declaration of Independence and modern political rhetoric.

-

Source: Jeannette Rankin Papers

-

-

Voting Records on War (WWI & WWII)

-

Resource: Congressional voting roll call records.

-

Activity: Have students examine and debate Rankin’s anti-war votes in context.

-

Source: National Archives’ Congressional Records

-

Carry the Torch

Carry the Torch

- Jeannette Rankin, “Let the People Know, Speech at Carnegie Hall,” March 2, 1917, Jeannette Rankin Papers, box

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 2.

- “John Rankin Ends Notable Life.” The Missoulian, May 4, 1904, p. 8.

- Norma Smith, Jeannette Rankin, America’s Conscience (Montana Historical Society, 2002), 15.

- Jeannette Rankin, interview by Ted Harris, February 20, 1969, reel 26, Ted Harris Collection of Jeannette Rankin Materials, Special Collections of the University of Georgia, Athens.

- Tina Cassidy, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait?; Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the Right to Vote (Simon & Schuster, 2019), 150.

- “Recognition of Independence of Ireland to be Demanded,” Irish Standard, January 12, 1918, p. 1.

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 8.

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 9.

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 8.

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 13.

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 14, 16.

- Rankin, “Let the People Know,” 23.

- Jeannette Rankin, interview by John C. Board, August 29 and 30, 1963, Jeannette Rankin Papers, Special Collections of the University of Georgia, Athens, 38.

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Resolutions from the First Congress, The Hague, 1915, WILPF International, 1915; Lynn Dumenil, “Women, Politics, and Protest,” in The Second Line of Defense: American Women and World War I (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 161–98.

- Nadine Strossen, “Women’s Rights under Siege,” NDL Rev. 73 (1997): 207.

- Maud Stockwell to Jeannette Rankin, letter, March 31, 1925, Jeannette Rankin Papers. Swarthmore College Peace Collection, PA.

- WILPF memo, December 11, 1929, National Council for Prevention of War records, box 68, folder 1, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, PA.

- Lorissa Rinehart, Winning the Earthquake: How Jeannette Rankin Defied All Odds to Become America's First Congresswoman (New York: St. Martin's Press, forthcoming 2026), chap. 20.

- Lorissa Rinehart, Winning the Earthquake: How Jeannette Rankin Defied All Odds to Become America's First Congresswoman (New York: St. Martin's Press, forthcoming 2026), chap. 21-2.

- Lorissa Rinehart, Winning the Earthquake: How Jeannette Rankin Defied All Odds to Become America's First Congresswoman (New York: St. Martin's Press, forthcoming 2026), chap. 23.

- June 11, 1970, newscast, The Huntley-Brinkley Report, included in interviews, and speeches from 1970–1972, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Harvard University, accessed November 18, 2024, https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:RAD.SCHL:38825402.

MLA – Rinehart, Lorissa. (2025). “Jeanette Rankin.” National Women’s History Museum. Date Accessed.

Chicago – Rinehart, Lorissa. “Jeanette Rankin.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025. www.womenshistory.org/educationresources/biographies/Jeanette-Rankin.