Gertrude B. Elion

Gertrude B. Elion was one of three recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988 “for their discoveries of important principles for drug treatment.”

In the 1950s, Elion and George Hitchings developed a systematic method for rational drug design, as opposed to the much less efficient and relatively haphazard trial and error approaches that preceded.

In addition to revolutionizing pharmaceutical design overall, she was particularly effective in synthesizing drugs for illnesses like leukemia, gout, herpes, and malaria.

“We were exploring new frontiers, since very little was known about nucleic acid biosynthesis or the enzymes involved with it… Each series of studies was like a mystery story in that we were constantly trying to deduce what the microbiological results meant, with little biochemical information to help us… When we began to see the results of our efforts in the form of new drugs which filled real medical needs and benefited patients in very visible ways, our feeling of reward was immeasurable.”

Gertrude B. Elion, Nobel Biography

Early Life

“I was born in New York City on a cold January night when the water pipes in our apartment froze and burst. Fortunately, my mother was in the hospital rather than at home at the time,” recounts Dr. Getrude B. Elion. She was the daughter of Jewish immigrants, her parents each having come to the U.S. as teenagers. Her father arrived from Lithuania at age 12 and went on to become a dentist, while her mother emigrated when she was 14 from a region of Poland that, at the time, was part of Russia. After the birth of her younger brother, the family moved from Manhattan to the Bronx when Elion was seven.

As Elion later wrote,

“I was a child with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and remember enjoying all of my courses almost equally. When it came time at the end of my high school career to choose a major in which to specialize I was in a quandary. One of the deciding factors may have been that my grandfather, whom I loved dearly, died of cancer when I was 15. I was highly motivated to do something that might eventually lead to a cure for this terrible disease. When I entered Hunter College in 1933, I decided to major in science and, in particular, chemistry.”

Figure 1. Elion, age three, with her mother.

Like so many others of the time, her father had invested heavily in the stock market and been bankrupted by the 1929 crash, though he was able to keep his practice open and continue working. “Had it not been that Hunter College was a free college, and that my grades were good enough for me to enter it, I suspect I might never have received a higher education,” Elion later wrote.

“I remember my school days as being very challenging and full of good comradery among the students. It was an all-girls school and I think many of our teachers were uncertain whether most of us would really go on with our careers. As a matter of fact, many of the girls went on to become teachers and some went into scientific research. Because of the depression, it was not possible for me to go on to graduate school, although I did apply to a number of universities with the hope of getting an assistantship or fellowship.”

Early Career

Due to the Great Depression, jobs were scarce at this time. The few that were available in laboratories were not open to women. Elion secured a three-month role teaching biochemistry at the New York Hospital School of Nursing. She met a chemist who was looking for a lab assistant; although unpaid for the first six months, she decided the experience would be worth it. “I stayed there for a year and a half and was finally making the magnificent sum of $20 a week,” she later wrote.

With her own savings and support from her parents, she began graduate studies at New York University in fall 1939. “I was the only female in my graduate chemistry class but no one seemed to mind, and I did not consider it at all strange,” she recalled.

After a year, she had completed the required classes, but still needed to do the research component to earn her Master’s in chemistry. She began teaching chemistry, physics and general science in high schools, doing her research at night and on weekends and finally earning her Master of Science in 1941.

Elion was able to find a job, but it was not particularly satisfying work, as she later recounted:

“By this time, World War II had begun and there was a shortage of chemists in industrial laboratories. Although I was finally able to get a job in a laboratory, it was not in research. I did analytical quality control work for a major food company. After a year and a half, during which I learned a good deal about instrumentation, I became restless because the work was so repetitive and I was no longer learning anything. I applied to employment agencies for a research job, and was chosen to go to a laboratory at Johnson and Johnson in New Jersey. Unfortunately, that laboratory was disbanded after about six months.”

Though unfortunate at the time, it would prove beneficial in the long run, leaving her available when opportunity, and chemist George Hitchings, came knocking.

WWII and Work with Hitchings

In 1942, Hitchings had begun working at Burroughs Wellcome Research Laboratories, part of the British pharmaceutical firm Burroughs Wellcome and Company (now part of GlaxoSmithKline). Two years later, he hired Elion as a lab assistant. It was one of several positions she was offered at the time, and Elion accepted because it “intrigued me most.”

“My thirst for knowledge stood me in good stead in that laboratory, because Dr. Hitchings permitted me to learn as rapidly as I could and to take on more and more responsibility when I was ready for it. From being solely an organic chemist, I soon became very much involved in microbiology and in the biological activities of the compounds I was synthesizing. I never felt constrained to remain strictly in chemistry, but was able to broaden my horizons into biochemistry, pharmacology, immunology, and eventually virology.”

She wasn’t only learning in the lab—eager to earn her doctorate, she started going to Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute at night. But after years of commuting (the lab was in Tuckahoe, about 25 miles north of Brooklyn), she was told she could no longer continue pursuing it on a part-time basis. It was a pivotal moment: she had to decide whether to stick with the doctoral program or her work at Wellcome. She chose her work.

“Years later, when I received three honorary doctorate degrees from George Washington University, Brown University and the University of Michigan, I decided that perhaps that decision had been the right one after all,” she wrote, “The work became fascinating almost from the very beginning. We were exploring new frontiers, since very little was known about nucleic acid biosynthesis or the enzymes involved with it… Each series of studies was like a mystery story in that we were constantly trying to deduce what the microbiological results meant, with little biochemical information to help us.”

Previously, drug development had originated with trial and error—someone had an idea and tested it to see if it worked or not. Hitchings believed there was a more strategic approach, which today is known as rational drug design. Inspired by the development of sulfa drugs – some of the first widely used antibiotics—he and Elion investigated substances that could interfere with the metabolism of microbes, the way sulfa drugs did. Hitchings wanted to target the synthesis of nucleic acids at a cellular level, as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) determine the genetic composition of cells and set the process of protein creation. If they could block the nucleic acids of bacteria, viruses, cancer cells and other harmful living matter in the body, they could slow or even stop the resulting diseases.

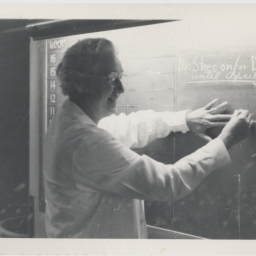

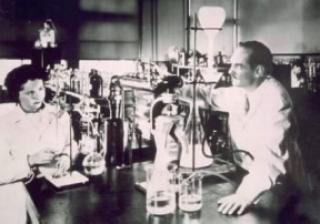

Figure 2. Elion working in the Wellcome Pharmaceutical Laboratory.

Elion studied purines, including adenine and guanine (two of the building blocks of DNA, along with cytosine and thymine) and soon found that bacterial cells needed certain purines to produce DNA—if they could block those purines, they could stop the production of DNA and, therefore, cell growth.

By 1950, Elion and Hitchings were able to synthesize two antimetabolites—chemicals that interfere with metabolism—called diaminopurine and thioguanine. Structured to mimic adenine and guanine, they attracted metabolic enzymes that attached to the diaminopurine and thioguanine instead of the natural purines, blocking the production of DNA. Their first major success, the drugs proved effective in treating leukemia. Elion later developed 6-mercaptopurine (also known as 6-MP and Purinethol); she spent six years researching the most effective combination of 6-MP with other drugs to battle childhood leukemia, and today this approach is able to cure most patients. “When we began to see the results of our efforts in the form of new drugs which filled real medical needs and benefited patients in very visible ways, our feeling of reward was immeasurable,” Elion later wrote.

The discovery that some of the drugs they developed would suppress the immune system led to development of a new drug, Imuran (azathioprine), which could be used in organ transplants to prevent the immune system from attacking and rejecting the new organ. The team’s allopurinol (Zyloprim) can treat gout, which is caused by the buildup of uric acid in joints, by reducing the body’s production of uric acid.

In the 1960s, Elion and Hitchings established that drugs targeting bacterial and viral DNA could be used to fight infectious diseases. This led to the anti-malaria drug pyrimethamine and trimethoprim (Septra), used to treat meningitis, septicemia and bacterial infections of the urinary and respiratory tracts.

Later Life and Career

Elion was promoted several times, becoming Head of the Department of Experimental Therapy in 1967, a post she would fill until retiring in 1983. “This department was sometimes termed by some of my colleagues a “mini-institute” since it contained sections of chemistry, enzymology, pharmacology, immunology and virology, as well as a tissue culture laboratory. This made it possible to coordinate our work and cooperate in a manner that was extremely useful for development of new drugs,” she explained.

Her ongoing research was key to developing acyclovir, an antiviral that proved effective against herpes. Though initially synthesized by another scientist, Elion was the one to determine exactly how it worked. Also known as Zovirax, acyclovir disrupts the replication of the herpesvirus, but not other viruses, which established that drugs can selectively target viruses. This principle would lead to Elion’s colleagues later developing the AIDS drug azidothymidine (AZT).

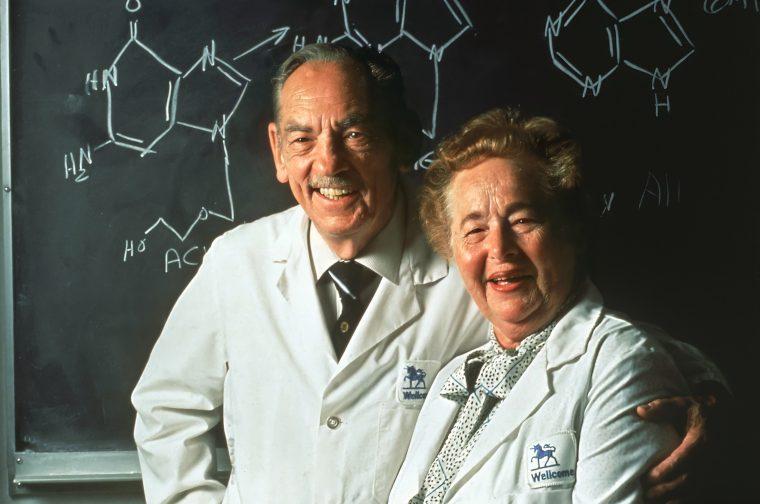

Figure 3. Elion and Hitchings after winning the Nobel Prize in 1988.

After retiring in 1983, Elion remained involved with Burroughs Wellcome as a scientist emeritus and consultant. She also became a research professor of medicine and pharmacology at Duke University, having followed the company when the lab moved from New York to Research Triangle Park, North Carolina in 1970.

“In a sense, my career appears to have come full circle from my early days of being a teacher to now sharing my experience in research with the new generations of scientists,” she observed.

Five years after she retired—Elion, Hitchings and James Whyte Black jointly received the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries of important principles for drug treatment.”

In 1991, Elion became the first woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Impact and Legacy

Gertrude B. Elion’s long-term impact can be seen in every person who’s ever benefitted from the drugs she developed, or contributed to. Science is a cumulative field, with people building on the work of their predecessors and contemporaries, and Elion laid an incredible foundation that other scientists of all genders continue to build on today. Although not as public a figure as some women in STEM, she stands as one of many examples of how, when given a chance, women and their work can change the world.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Photograph Analysis

Gertrude Elion and George Hitchings researching in a laboratory.

Observe

- Describe what you see.

- What do you notice first?

- What people and objects can be seen?

Reflect

- Why do you think this image was made?

- What is happening in the image?

- What is the emotional tone of the image?

Question

- What do you wonder about?

- What kind of thoughts does this photo invoke?

Gertrude B. Elion, “Biographical,” The Nobel Prize, 1988, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1988/elion/biographical/

“George Hitchings and Gertrude Elion,” Science History Institute, https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/george-hitchings-and-gertrude-elion/

Kristine Larsen, “Gertrude Elion,” Jewish Women’s Archive, February 27 2009, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/elion-gertrude-belle

MLA — Tyra, A. "Gertrude B. Elion." National Women's History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago — Tyra, A. ""Gertrude B. Elion." National Women's History Museum. 2025. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/Gertrude-Elion

Dale DeBakcsy, “Killer of Cancer, Slayer of Viruses: The Many Medicines of Nobel Prize Laureate Gertrude Elion,” The Women in Science Archive, April 22 2023, https://www.wisarchive.com/post/killer-of-cancer-slayer-of-viruses-the-many-medicines-of-nobel-prize-laureate-gertrude-elion