Jane Cooke Wright

Summary

-

Coming from a family of medical trailblazers, Jane Cooke Wright transitioned from aspiring artist to accomplished physician, eventually succeeding her father at Harlem Hospital and leading groundbreaking clinical trials that introduced new cancer treatments, including methotrexate.

-

Over her 40-year career, Wright rose to national prominence as a professor, dean, and medical policy leader, while raising a family and mentoring future physicians; her legacy includes over 135 scientific papers and transformative contributions to modern oncology.

Quote

“She never gives up and never sees the 'No' in anything, she just tries to think outside of the box and how it can be done and solved.”

- Dr. Jane Cooke Wright’s daughter, Dr. Alison Jones.

A Puzzle to Solve

Never afraid of a puzzle, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright was an early aficionado of the Rubik’s Cube, popularized in the 1980s when she was in her 60s. According to her daughter, Alison Jones, she insisted on solving every Rubik’s Cube she saw no matter the other tasks at hand. So too, did she approach the challenges of working as a Black female physician in cancer research from the 1940s into the 1970s. According to her daughter, from a 2010 interview:

“She never gives up and never sees the 'No' in anything, she just tries to think outside of the box and how it can be done and solved.”

No obstacle was too high for her, and no disease too daunting. She was among the first to use drugs to treat cancer despite those who doubted her research’s viability, and in doing so transformed the medical field (Sandra M. Swain, 646-8).

Early Life

Figure 1, Jane C. Wright as a young girl, ca. 1921. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

Jane Cooke Wright was born in 1919 in New York City, the first of two daughters of Corrine Cooke and Louis Tompkins Wright. Her father, one of the first Black physicians to graduate from Harvard Medical School, broke many barriers in his early career, including being the first Black physician to be a New York police surgeon. He set a purposefully high example for his daughters to follow.

Jane Cooke attended Smith College with a four-year academic scholarship to study art. She was initially reluctant to turn to medicine, not wanting to stand in the shadows of her father’s already impressive career.

“I was planning to become a renowned artist.”

Dr. Jane C. Wright, in an Ebony interview (1968)

However, in her junior year, her father convinced her to go into the family business and study pre-med. Upon finishing her studies at Smith, she received a full academic scholarship at the New York Medical College (“Dr. Jane Cooke Wright,” Changing the Face of Medicine).

Figure 2, Jane Cooke Wright, Class of 1942, Smith College Medalist

Medical Training

Jane Wright followed in her father’s footsteps, graduating with honors from New York Medical College in 1945. She completed her residency at Harlem Hospital, during which she married David Jones, Jr., himself a graduate of Harvard Law. She had her first child with Jones in 1948 and returned after a six-month leave to complete her training at Harlem Hospital as chief resident (“Dr. Jane Cooke Wright,” Changing the Face of Medicine).

In the early twentieth century, Harlem was a haven of Black creativity and culture. While most known for the Harlem Renaissance artists, musicians, and authors such as Zora Neale Hurston, Augusta Savage, and Josephine Baker, Black scientists and physicians also experienced greater opportunities to contribute within their fields in this urban space.

After serving as a staff physician with the New York City Public Schools, she utilized her familial connection in medicine and joined her father at the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital, where he was the director (“Dr. Jane Cooke Wright,” Changing the Face of Medicine).

Oncology and Chemotherapy Research

At the time she entered the field, Chemotherapy was still in experimental stages. Most of her contemporary physicians did not see the point in researching drug treatment to cancer and solely focused on surgery or radiation. Yet, ever optimistic, perseverant, and striving to solve a puzzle few would attempt, Dr. Jane Wright still tried (Sandra M. Swain, 646-8).

“She was a woman in a man's world, and gently set about to change it, was creative, very well regarded, not bashful.”

-James F. Holland, M.D., professor of hematology, medical oncology, and oncological sciences at Mount Sinai School of Medicine

At Harlem Hospital, her father had focused the direction of research towards the investigation of anti-cancer chemicals. The pair worked together as a team with Dr. Louis Wright in the lab and Dr. Jane Wright performing patient trials. Very early on in their collaboration, they began to test new chemicals on leukemias and other lymphatic cancers, resulting in early remission results. Dr. Jane Wright herself was one of the first researchers to analyze anticancer agents by comparing tissue-culture response to patient response, and in doing so created innovative new techniques to treat through chemotherapy. She was well-known for her dedicated attention to detail and bedside manner, paying meticulous thought to patients that other physicians called a lost cause and treating them with the best of her ability and the latest research (Sandra M. Swain, 646-8).

When her father Dr. Louis Wright died in 1952, she took his place and led the research institution at the age of 33. She continued to honor his legacy by developing new techniques for administering even stronger drugs to treat the most difficult cancerous tumors, especially those that were deep within the body and untreatable through other means. Her careful attention to tracking results through a database she created allowed her to cross-reference the types of cancers and patient conditions in order to verify the effectiveness of her treatments (“Dr. Jane Cooke Wright,” Changing the Face of Medicine).

As many of her contemporaries and those who followed in her footsteps have noted, Wright’s laboratory and clinical trials introduced the nation and the world to a fountain of modern possibilities for cancer treatment. She was the first to study methotrexate, which is a drug that has widespread applications today for cancer and autoimmune diseases and remains essential to the health and wellbeing of millions of patients around the world. Her work in oncology laid the foundation for future studies that ultimately led to the development of sequential adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer and drug-based treatment regimens that transformed or even cured cancers from acute leukemia to lung cancer (Clifford A. Hudis, “A Eulogy in Honor of Jane C. Wright”).

Advocacy and Instruction

In the mid-1950s, Dr. Jane Wright shifted back into education and became an associate professor of surgical research at New York University as well as their director of cancer chemotherapy research. In 1964, she served on the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. Her research and recommendations brought forth the creation of a national network of treatment centers for these conditions. In 1967, she became a professor of surgery, head of Cancer Chemotherapy, and associate dean at New York Medical College. At this time in the United States, there were only a few hundred African American women physicians in the entire country, and Dr. Wright rose to unprecedented ranks in her career for a woman of her background (“Dr. Jane Cooke Wright,” Changing the Face of Medicine). She considered her return to the NYMC to be one of her greatest achievements. She spoke to Ebony at the time of her appointment:

“It’s like a wonderful homecoming for me. It’s like a dream.”

While working in a tremendously demanding field, both intellectually and emotionally, Dr. Wright also raised two daughters, both of whom went into medicine. One became a clinical psychologist and the other a psychiatrist. She also continued to nurture her artistic practice, creating landscapes in her limited spare time. Dr. Alison Jones spoke of her mother as a source of inspiration in 2010:

“I am not sure that when I was growing up we realized exactly how on the cutting edge she was. She was always just a very, very busy mother because she took her work duties very seriously and she was a modest person. She didn't boast about what she was doing.”

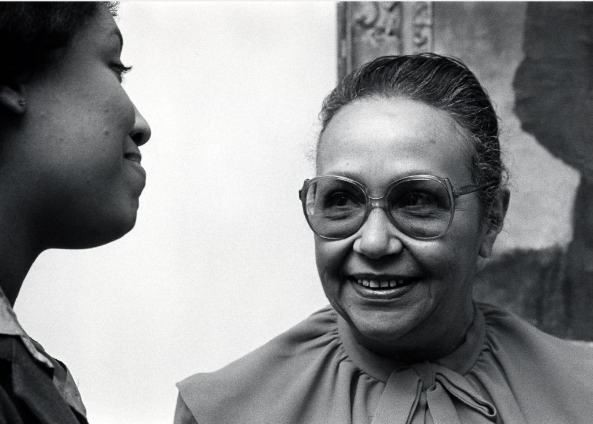

Figure 3, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright, recipient of the Otelia Cromwell Award, Smith College, April 1981.

She never stopped researching and advocating for innovative solutions to complex medical issues. She transformed the program to study stroke, heart disease, and cancer at New York Medical College and created specialized programs to instruct doctors in chemotherapy. She was one of the seven founding members of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and was the only founder who was a woman or non-white (Clifford A. Hudis, “A Eulogy in Honor of Jane C. Wright”). In 1971, Dr. Wright was the first woman to be president of the New York Cancer Society. She retired in 1987 after a forty-year career (Dr. Jane Cooke Wright,” Changing the Face of Medicine). She died at home on February 19, 2013, at the age of 93. In her legacy she left other 135 scientific papers, contributions to 9 books, numerous awards and honors such as the Smith Medal from Smith College, the Spirit of Achievement Award from Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and the thousands of lives she touched with her dedicated research and care to treat cancer (Sandra M. Swain, 646-8).

Figure 4, Jane C. Wright at the New York Medical College class of 1945 reunion, ca. 1995. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

Works Cited

Works Cited

Hay, Amy M. "Wright, Jane Cooke." In Black Women in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hudis, Clifford A. “A Eulogy in Honor of Asco Founder Jane C. Wright, MD.” ASCO Connection (2013). https://connection.asco.org/do/eulogy-honor-asco-founder-jane-c-wright-md#:~:text=In%20a%202010%20interview%2C%20Dr,keep%20up%20the%20good%20fight.%E2%80%9D

"Jane Cooke Wright: Innovative Oncologist and Leader in Medicine." The Lancet 400, no. 10360 (Oct 15, 2022): 129

Jenkins, Edward S. "The Remarkable Dr. Jane Cooke Wright." Afro - Americans in New York Life and History (1977-1989) 13, no. 2 (Jul 31, 1989): 57.

Swain, Sandra M. “A Passion for Solving the Puzzle of Cancer: Jane Cooke Wright, M.D., 1919-2013.” The Oncologist vol. 18,6 (2013): 646–648.

Trigg, Mary K. Great Lives From History: American Women. Amenia, NY: Salem Press, 2016.

Watts, Geoff. "Jane Cooke Wright." The Lancet 381, no. 9875 (Apr 20, 2013): 1354.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

“Homecoming for Jane Wright,” Ebony, May 1968 (pg 72-77)

-

What details about Dr. Wright’s life do you learn about in this article? How is it different from a biography, or similar?

-

What do you notice about the advertisements in this magazine that are alongside the article? What do they tell you about the time in which Dr. Wright lived?

-

Why was this article written? What are the motivations of the publication to write about Dr. Wright in this way?

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

Diann Jordan, Sisters in Science: Conversations with Black Women Scientists (2006).

Related Biographies

Related Biographies

Carry The Torch

Carry The Torch

How to Cite this Page

How to Cite this Page

McKelvie, Lydia. “Jane C. Wright.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

McKelvie, Lydia. “Jane C. Wright.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025 link.