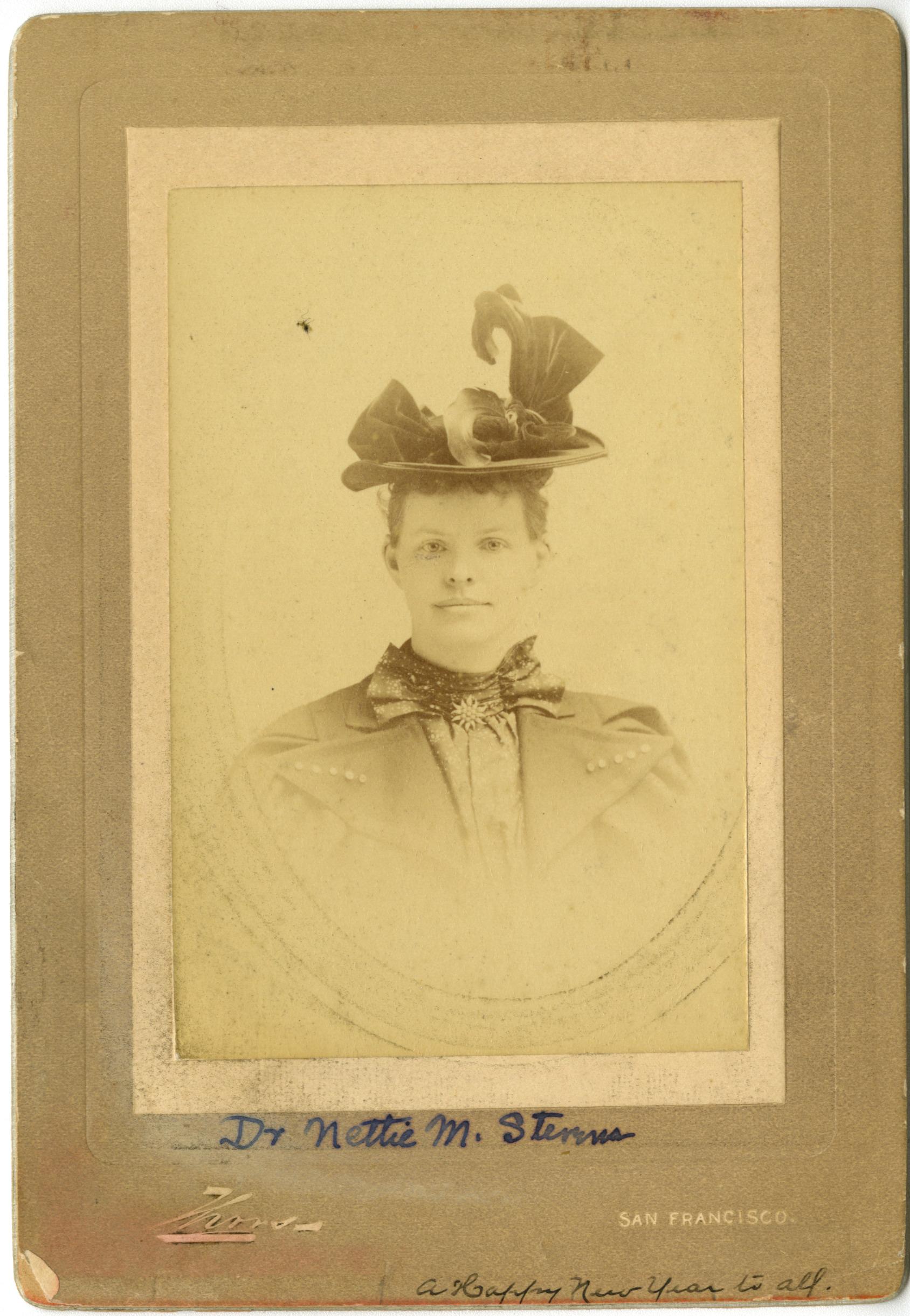

Nettie Stevens

Nettie Stevens was a groundbreaking geneticist who discovered sex chromosomes.

She came to the field of science research after spending decades as a science teacher, studying at Stanford and Bryn Mawr and traveling to Germany and Italy.

After her untimely death, her male contemporaries were credited with her scientific breakthroughs, one even winning a Nobel Prize for her discovery of sex chromosomes.

“Without Stevens’ discoveries, it is impossible to know where the field of genetics would be today. Yet, like many other female researchers, her work has been consistently undervalued.”

Anjali Dhanekula from Hidden Histories: Nettie Stevens (2023)

Early Life

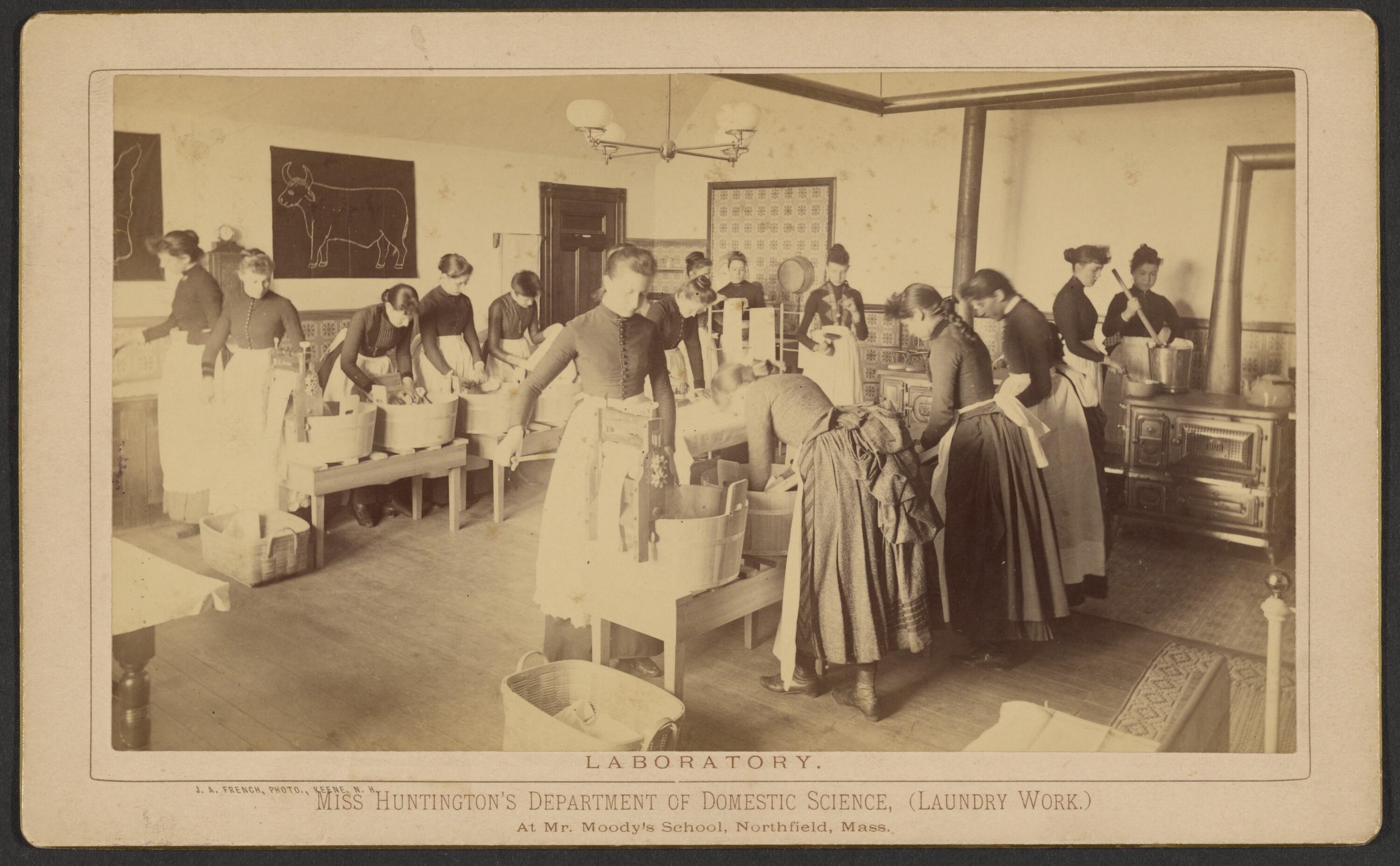

Nettie Maria Stevens was born on July 7, 1861, in Cavendish, Vermont to Julia and Ephraim Stevens. Her mother died in 1863 and her father remarried, moving the family to Westford, Massachusetts, when she was a young girl. Her father had accumulated enough income to send his children to school to be trained for a vocation. For young women, this meant a career in teaching if they received adequate training in school subjects, or in the domestic sciences, such as laundry, if they did not. Stevens attended the Westford Academy, one of the oldest co-educational schools in the United States, where she thrived in her Greek and Latin courses. She graduated with top grades at the age of 19.

Figure 1. School of Domestic Science, ca. 1890.

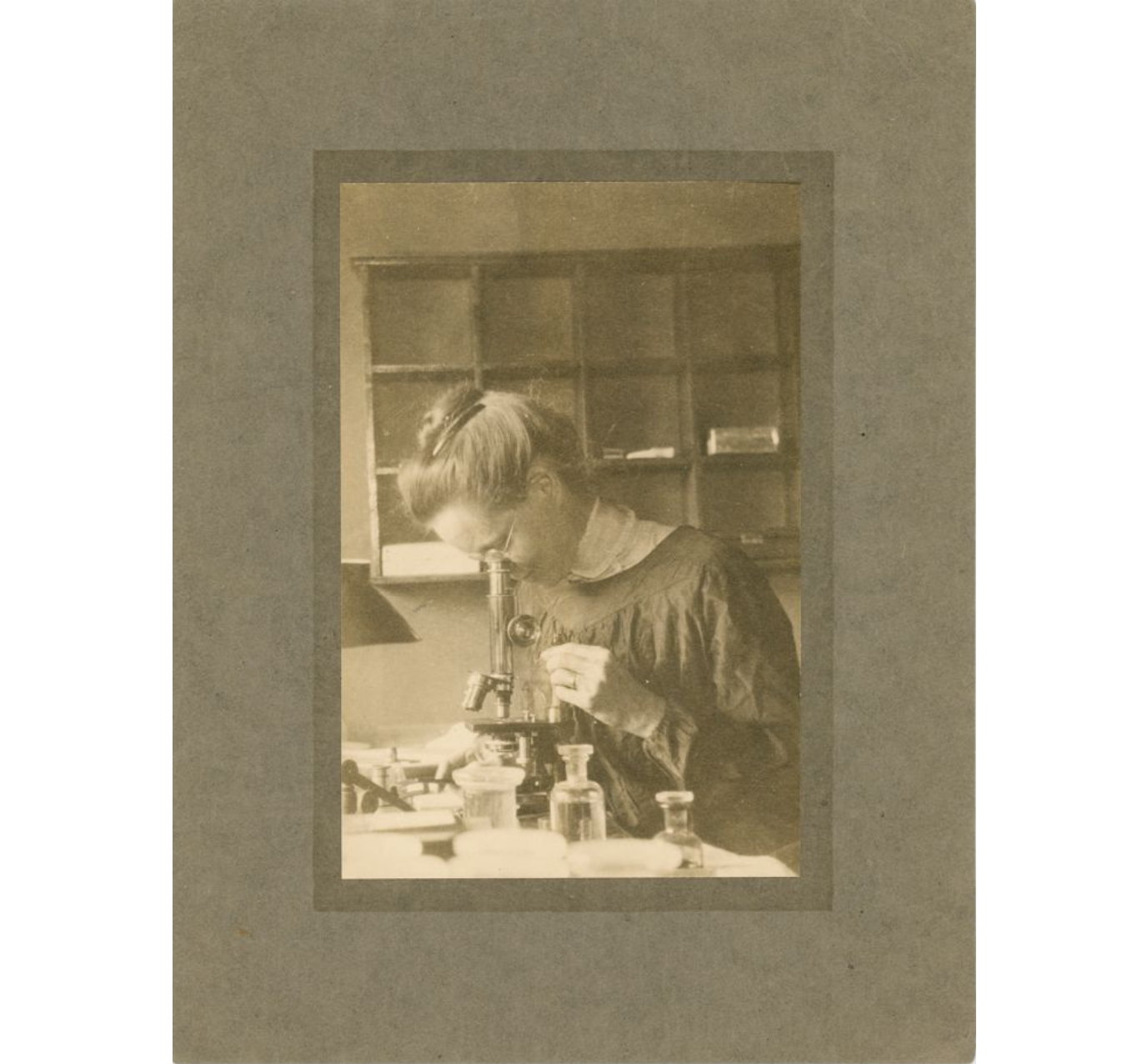

Figure 2. Nettie Stevens, N.D.

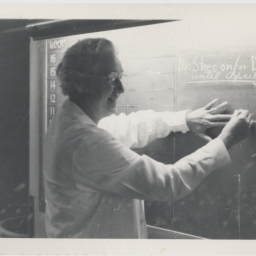

Teaching Career

After graduation, Stevens became a high school teacher in Lebanon, New Hampshire. However, she dreamed of furthering her education in a direction that none of her family or peers could have imagined. She worked to save money towards that goal, investing her money back into her degrees throughout her education. First, she attended the Westfield Normal School, a teacher’s college. She continued her pattern of working, saving, and self-funding her education until she graduated. She sought additional training in the sciences, enrolling in 1896 at the age of 35 at the newly established Stanford University.

Figure 3. School teacher and students on field trip, 1899.

University, Travel, and Early Research Science

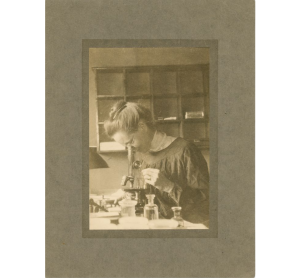

Figure 4. Nettie Stevens, while a student at Bryn Mawr, 1903.

While at Stanford, a co-educational institution since its founding in 1885, Stevens’ zoological and genetic research began to develop in earnest. Stevens’ research focused on morphology, which is the study of the forms of living organisms, and cytology, the study of the structure and function of plant and animal cells. She spent her summers at Stanford working at the Hopkins Marine Station, the oldest marine laboratory on the West Coast. She received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees by 1900. Her master’s thesis centered on her detailed observations of the life cycle of two ciliates, single-celled animals which she focused on throughout her career.

Figure 5. Nettie Stevens (rear, second from left) with Boveri family in Würzburg, Germany. 1903.

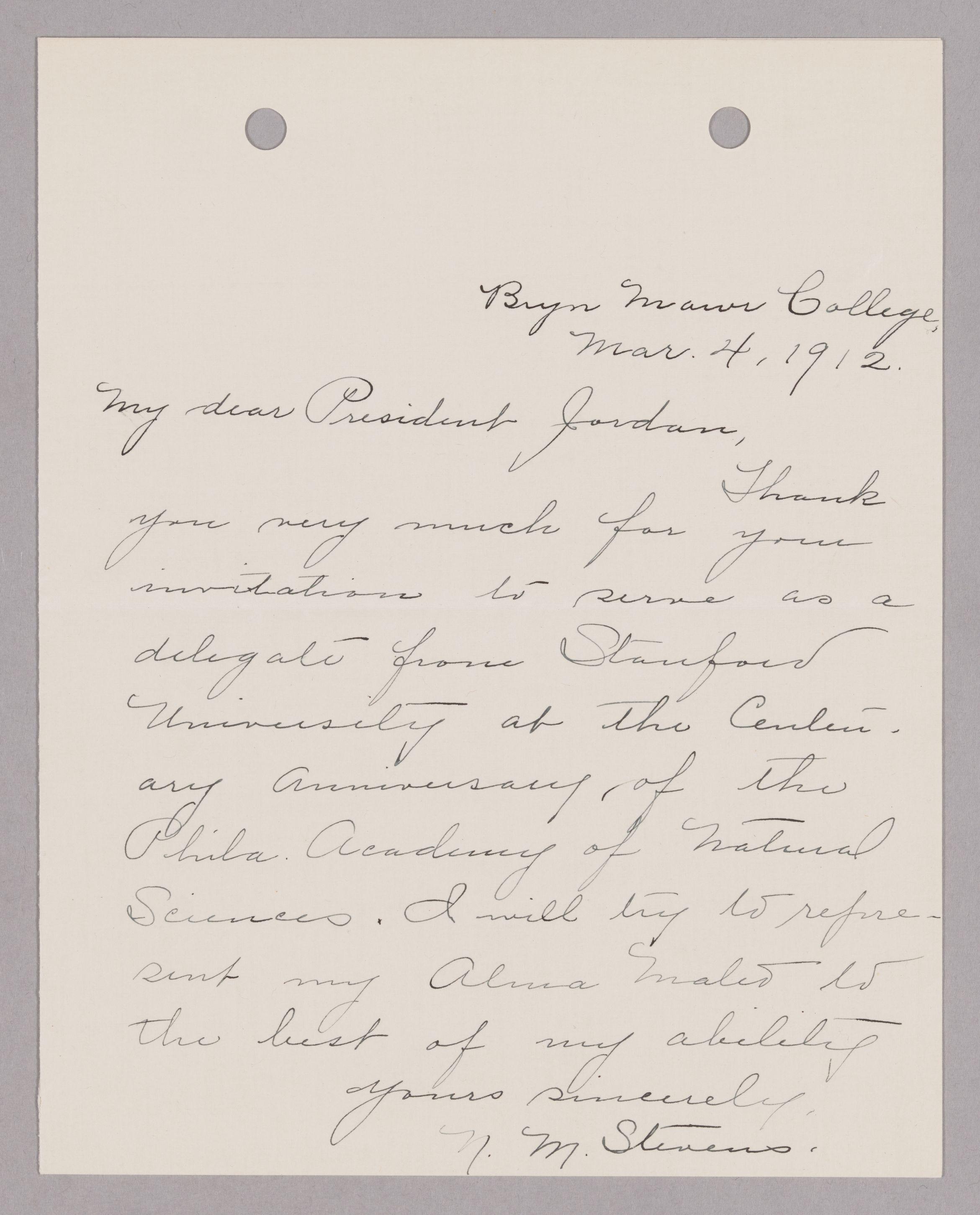

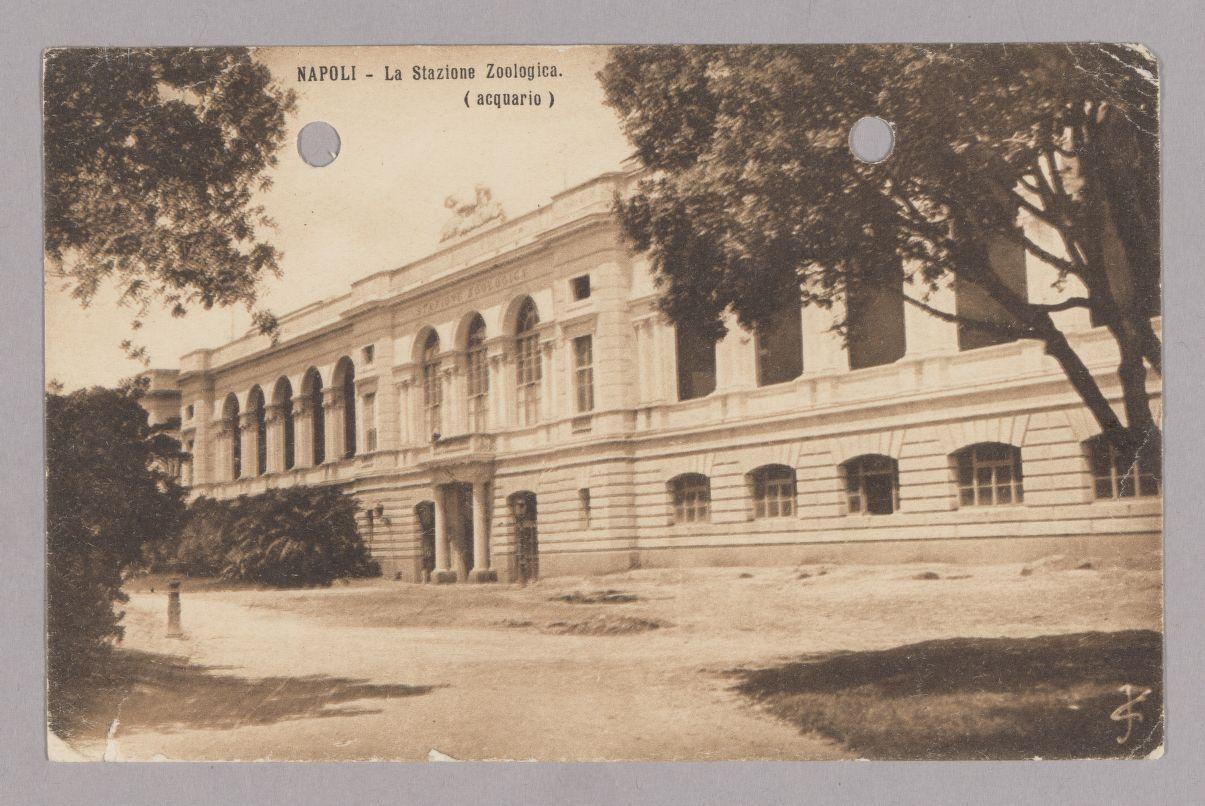

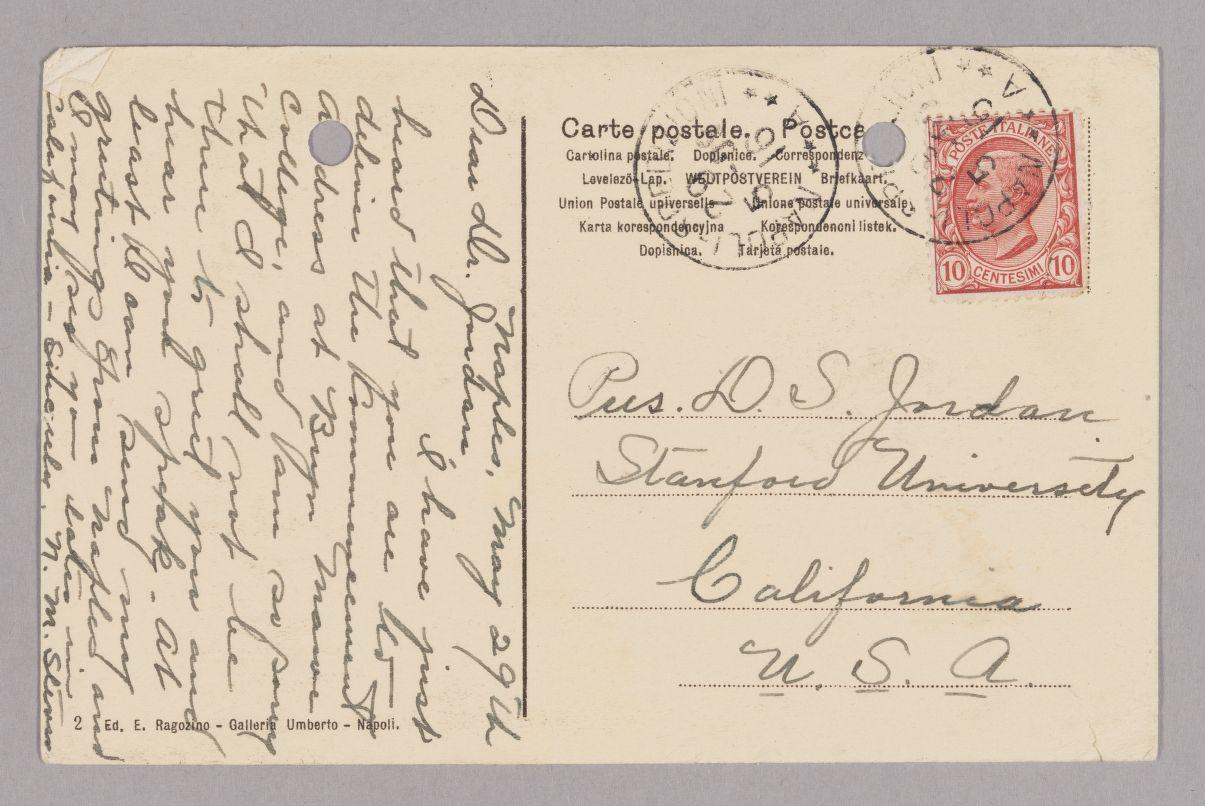

Stevens further advanced her education at Bryn Mawr College in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, a burgeoning center for biological research, and began her doctorate under the advisement of Thomas Hunt Morgan. In 1901, Stevens received the Bryn Mawr President’s European Fellowship, allowing her to conduct research at the Naples Zoological Station and the Zoological Institute of the University of Würzburg in Germany. Stevens’ doctoral research expanded on her earlier publications, describing the microanatomy and regeneration patterns of a variety of ciliates. In 1903, she received her PhD.

Figure 7. Postcard from Nettie Stevens while working at the Zoological Station in Naples.

When Stevens was beginning her scientific research, the field of genetics was exploding in popularity and new developments abounded. Before Stevens, scientists such as Theodor Boveri, whom Stevens studied with in Naples, had already connected Gregor Mendel’s foundational research on heredity to chromosomes. However, many biologists at Stevens’ time did not believe that chromosomes could be the basis of the determination of sexes or of heredity alone.

Discovery of Sex Chromosomes

Over the course of human history, nearly all cultures have been fascinated and perplexed by the question of how sexes develop during pregnancy. Most ascribed this phenomenon to external factors. For example, in 15th-century Italy, women who were pregnant were told to eat warm foods and to avoid sitting on the cold ground to conceive a boy. In ancient Greece, one might eat lettuce and drink white wine in order to give birth to a girl. Not until the early 1900s did scientists begin to discover that biological sex is determined by genetics, transforming our modern-day ideas of human development, pregnancy, and chromosomes. Dr. Nettie Stevens was the first to provide concrete evidence for the genetic basis of sex in her two-part study: Studies of spermatogenesis (1905).

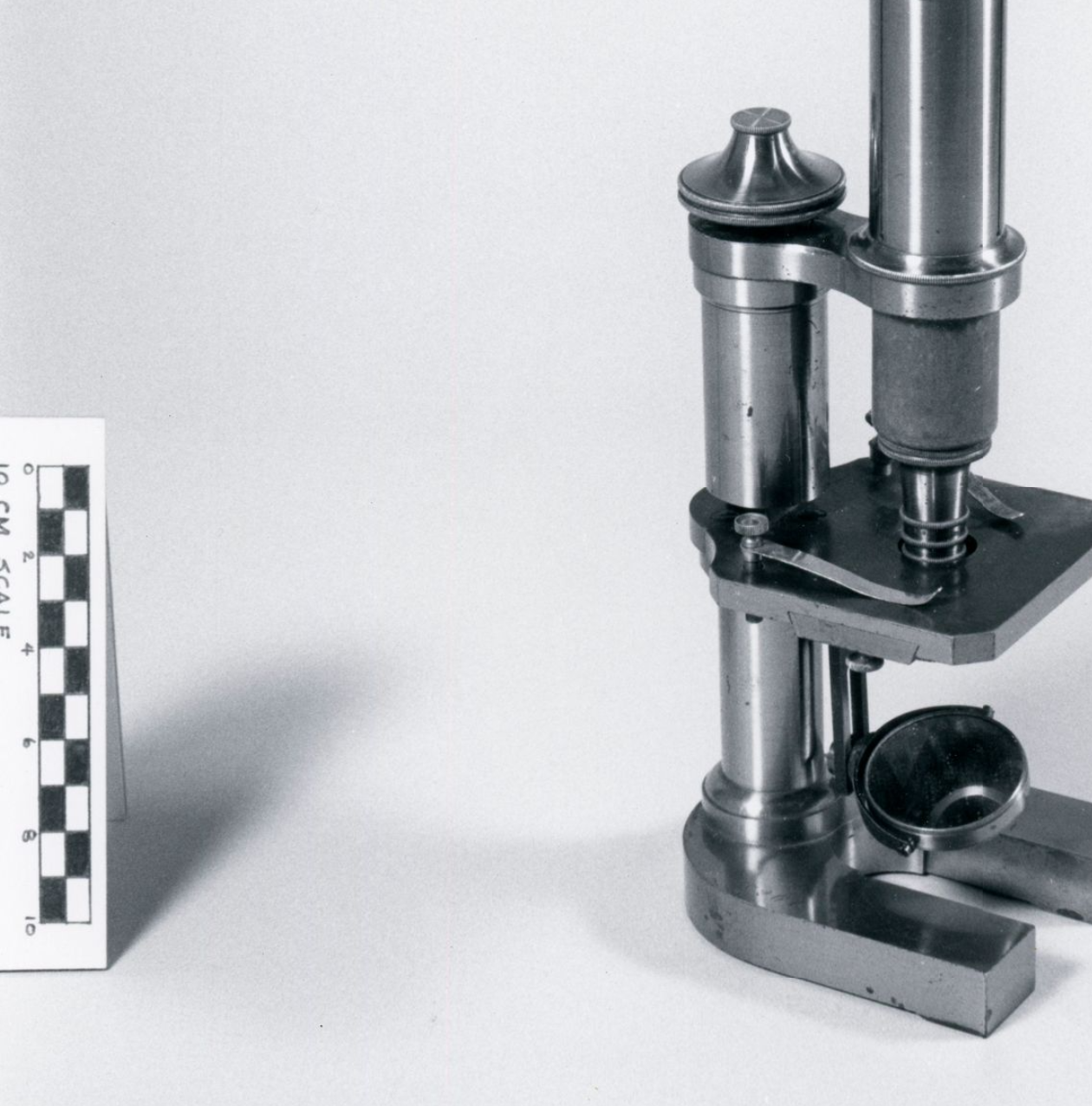

Stevens produced this study as a postdoctoral research assistant at the Carnegie Institute of Washington. Through careful examination and experimentation, Stevens showed that the inheritance of the Y chromosome is connected with male development in several insect species. In her experiments, she noticed that male mealworms produced sperm with either a large chromosome (the X chromosome) or sperm with a small chromosome (the Y chromosome), but female mealworms only produced eggs with large chromosomes (X). She concluded that paternal chromosomes are responsible for sex determination.

Figure 8. Nettie Stevens’ Microscope

Recognition of Her Research

After her work at the Carnegie Institute of Washington, Stevens returned to Bryn Mawr as a research associate. She continued to focus on spermatogenesis and to innovate in the field of genetics and zoology. For example, she may have been the first to discover B chromosomes, non-essential chromosomes present in all sexually reproducing mammals, suggesting a relationship between them and sex chromosomes. In 1910, Stevens was included in the top 1000 “men of science,” as one of the eighteen women recognized. In 1912, Stevens finally received a research professorship position at Bryn Mawr but tragically died of breast cancer before she could begin. She was 50 years old. In an eleven-year career, she published a remarkable 38 manuscripts.

Stevens’ original discovery of sex chromosomes has often been falsely attributed to Edmund Beecher Wilson, a former professor at Bryn Mawr who was also heavily involved in her doctoral research. While Wilson’s research on sex chromosomes was published in the same year, 1905, as Stevens’ research on the same topic, Stevens was the first to concretely show that the Y chromosome determined sex. She would continue to build on this work throughout her career, further substantiating her claim as the discoverer of sex chromosomes by being the first to identify heterochromosomes. The rigorousness of her research and her determination to learn all that she could about sex chromosomes was apparent to her peers, and her depth of knowledge was unparalleled in the field during her lifetime.

Despite her contributions to science, Stevens, like other female scientists such as Rosalind Franklin, Alice Ball, and Esther Lederberg, has been functionally erased from history. In 1906, Wilson and Thomas Hunt Morgan were invited to speak on their theories of sex determination at a conference, while Stevens was not. Hunt, who was Stevens’ doctoral advisor, would later take some of the credit for Stevens’ work and even go on to claim a Nobel Prize in 1933 “for his discoveries concerning the role played by the chromosome in heredity,” despite the fact that he did not accept the theory of chromosomal inheritance until decades after Stevens had proven it.

Without the work of Nettie Stevens, the modern world would miss critical developments in research on Turner Syndrome and Down Syndrome, as well as many other practical applications of chromosomal heredity. Today, she is recognized in the National Women’s Hall of Fame and at the Westfield State University Dr. Nettie Maria Stevens Science and Innovation Center.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

-

What do you notice about this portrait? What are the objects around Stevens?

-

How is Stevens portrayed, and is it similar or dissimilar from portraits of male scientists from the period?

-

What can you see about her character or personality from this portrait?

Nettie Stevens, second from the left, with group on the beach near the Cape of Messina, Italy. 1909.

-

Notice the clothes, the environment, and the poses of the people in this photo. How are they dressed? Is it mostly women or men?

-

What do you think that they’re relationship is to each other, and why?

-

From this photo, what do you imagine it was like to travel to another country in this period?

Ashworth Jr., William B. “Nettie Maria Stevens.” Linda Hall Library. July 7, 2022. https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/nettie-maria-stevens

Dhanekula, Anjali. “Hidden Histories: Nettie Stevens.” Yale Scientific. May 12, 2023. https://www.yalescientific.org/2023/05/hidden-histories-nettie-stevens

“Dr. Nettie Stevens: Making genetics history with mealworms.” Helix. February 16, 2018. https://www.helix.com/blog/nettie-stevens

Carey, Sarah B., Laramie Aközbek and Alex Harkess. “The contributions of Nettie Stevens of the field of sex chromosome biology.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Volume 377, Issue 1850. May 9, 2022. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2021.0215

“Nettie Stevens Biography.” Carnegie Science. Accessed November 7, 2025. https://carnegiescience.edu/news/nettie-stevens-biography

Smith, Kaitlin, "Nettie Maria Stevens (1861-1912)." Embryo Project Encyclopedia. June 20, 2010. 2010. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/nettie-maria-stevens-1861-1912

Winterer, Caroline. “Victorian Antigone: Classicism and Women’s Education in America, 1840-1900.” American Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2001): 70–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30041873.

MLA — McKelvie, Lydia. “Nettie Stevens.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago — McKelvie, Lydia. “Nettie Stevens.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/nettie-stevens .