Helen Taussig

Biography Summary

Dr. Helen Brooke Taussig co-developed the Blalock-Taussig shunt in the 1940s, revolutionizing the treatment of congenital heart defects in infants and saving countless lives.

As a deaf woman in early 20th-century America, she overcame gender and physical barriers in medicine to become the founder of pediatric cardiology.

“Before Taussig, every president of the American Heart Association was a man. She opened the door to women.”

Laura Williamson, American Heart Association News, March 28, 2024

Early Life and Education

Helen Brooke Taussig was born on May 24, 1898, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her father, Frank W. Taussig, was a renowned economist at Harvard University, and her mother, Edith Thomas Guild, was one of the first women to attend Radcliffe College, studying biology and zoology (National Library of Medicine). Academia and learning were important pillars in their household. Her grandfather also had strong roots in education as a teacher at a school for blind students and maintained a lifelong interest in science. Taussig credited her lineage, saying she descended from “a direct line of teachers, and an indirect line of doctors” (National Library of Medicine).

Taussig’s childhood was marked by significant challenges. Her mother died of tuberculosis when she was eleven years old, and she struggled academically due to severe dyslexia. Later, after a serious illness, she became partially Deaf (Lowell Milken Center). While she faced some struggles academically, she was a great athlete, later becoming a champion tennis player (Changing the Face of Medicine).

College Years

With her father’s support, Taussig found tools that accommodated her learning needs. She graduated from the Cambridge School for Girls in 1917 and initially attended Radcliffe College before transferring to the University of California, Berkeley, where she earned her bachelor's degree in 1921. She aspired to study medicine at Harvard University, but the institution did not admit women at that time. Although Harvard allowed her to take courses, it refused to award a degree to a woman (National Library of Medicine).

This gender discrimination led Taussig to explore other options, ultimately enrolling at Boston University’s Medical School. There, she studied biology and anatomy, though her lectures were segregated from those of male students. According to the Lowell Milken Center, she was even barred from speaking to male classmates for fear of “contamination”. Robays (2016) noted that anatomical illustrations were viewed in secluded rooms to prevent interaction between genders. While writing a thesis on the muscular bundles of a cow’s heart, Taussig discovered her interest in cardiology. Her advisors encouraged her to apply to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, one of the few institutions that accepted women. She was admitted and earned her Doctor of Medicine degree in 1927.

Early Career in Pediatrics

Taussig aspired to specialize in internal medicine, but when it came time to apply for residency, there was only one available position for a woman—and it was awarded to another student. She then pivoted to pediatrics (Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame). At the same time, she began volunteering at Harriet Lane Home, a heart clinic for children run by Dr. Edwards Park.

Young Taussig looking at a chest x-ray .

Founding Pediatric Cardiology

At the time, pediatric cardiology was a virtually nonexistent field. In 1930, Taussig became head of the cardiac clinic. Diagnosis relied heavily on auscultation—listening to the heart with a stethoscope. As her deafness worsened, she adapted by learning to lip-read and “listen with her fingertips” (National Library of Medicine). The invention of the fluoroscope, a portable X-ray machine, also enhanced her diagnostic capabilities (Heart).

The Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Shunt

In 1944, Taussig and Dr. Alfred Blalock developed a surgical procedure to treat "blue baby syndrome," a condition caused by a congenital heart defect that limited oxygenated blood flow between the heart and lungs (Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame). She observed that children with this condition often had a patent ductus arteriosus, a blood vessel that, when open, allowed for better oxygenation. Taussig hypothesized that creating a surgical shunt to mimic this condition could improve oxygen levels in these patients. At the time, “blue baby syndrome” accounted for 25% of deaths in children under the age of one and 70% of deaths in children before the age of 10 (Lowell Milken Center).

Collaborating with Blalock and surgical technician Vivien Thomas, the team developed a procedure to connect the subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery (Heart). he first Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt was performed in 1944 on a 15-month-old girl named Eileen Saxon (EBSCO). Although Saxon’s life was only briefly extended, the surgery proved that cyanotic heart defects could be treated surgically. After three successful surgeries, the team published their findings (Lowell Milken Center).

Taussig’s book, Congenital Malformations of the Heart, was published in 1947 and is a comprehensive clinical and anatomical study of heart defects present at birth. The book became foundational for cardiologists and surgeons treating children, helping to establish pediatric cardiology as a distinct medical specialty. It reinforced her title as the “mother of pediatric cardiology” (National Library of Medicine).

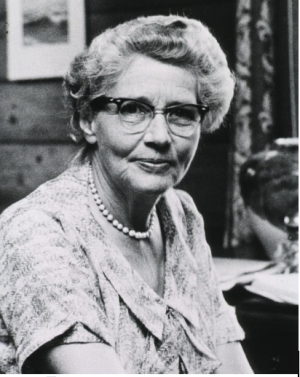

Portrait of Taussig which was later used as her the author picture of her book.

Image from the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives. Item 5933.

In 1954, Taussig received the Lasker Award for her contributions. Two years later, she became the first woman to receive a full professorship at Johns Hopkins University (Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame).

Advocacy and Later Life

Beyond her surgical innovations, Taussig was a vocal advocate for public health. In the early 1960s, she played a pivotal role in preventing the approval of Thalidomide in the United States. The medicine was initially used as an anti-epileptic treatment, sleep medication and sedative, as well as a medication to easy morning sickness in pregnant people (National Library of Medicine). After learning about the drug's teratogenic effects in Europe, she testified before the Food and Drug Administration, contributing to the decision to ban the drug in the U.S.

Legacy and Honors

Taussig retired from Johns Hopkins in 1963 but continued to teach, lecture, and conduct research. She remained active in the medical community, writing numerous scientific papers and advocating for various causes, including the use of animals in medical research and the legalization of abortion. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom (Heart).

Helen Taussig with Lyndon B. Johnson and group at unidentified White House event, possibly related to 1964 Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Image from the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives. Item 209773.

The following year, she became the first woman president of the American Heart Association. In 1972, she was named the first woman Master of the American College of Physicians. One year later, she was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York (Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame).

Taussig died in a car accident on May 20, 1986, just three days before her 88th birthday, while driving friends (National Library of Medicine).

Resources for Building Primary Source Strategies

Resources for Building Primary Source Strategies

Analyzing Primary Sources

Dr. Helen Taussig, 87, Dies: Led in Blue Baby Operation | Newspaper

New York Times article covering Taussig’s life and death.

Primary Source Inquiry

-

What does the language used in this obituary suggest about how women physicians were perceived in 1986, and how might that differ from today?

-

Why might the New York Times have chosen to highlight the “blue baby operation” over her other contributions (e.g., thalidomide testimony or academic milestones)? What does this editorial choice tell us about public memory or media priorities at the time?

-

According to this obituary, how did Dr. Taussig’s work influence medicine and public health policy, and what evidence does the article provide to support those claims?

-

If you compared this obituary to a modern biography or textbook entry on Dr. Taussig, what differences in focus or tone might you expect to find, and why?

Educator Notes

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Primary Sources guide learner inquiry.

American Heart Association. “Dr. Helen Taussig’s Work Saved ‘Blue Babies.’” American Heart Association News, March 28, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2024/03/28/dr-helen-taussigs-work-saved-blue-babies.

Evans, William N. “The Blalock-Taussig Shunt: The Social History of an Eponym.” Cardiology in the Young 19, no. 2 (2009): 119–28. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/10.1017/S1047951109003631.

Dyslexia Help at the University of Michigan. “Helen Taussig.” Success Stories. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://dyslexiahelp.umich.edu/success-stories/Helen%20Taussig.

EBSCO. “Blalock and Taussig Perform First ‘Blue Baby’ Surgery.” Research Starters: History. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/blalock-and-taussig-perform-first-blue-baby-surgery.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Helen Brooke Taussig.” Britannica. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Helen-Brooke-Taussig.

Johns Hopkins Medical Archives. “Helen B. Taussig Collection.” Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://medicalarchives.jhmi.edu/collection/helen-b-taussig-collection/.

Lowell Milken Center for Unsung Heroes. “Warrior of the Heart.” Lowell Milken Center for Unsung Heroes. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.lowellmilkencenter.org/programs/projects/view/warrior-of-the-heart/hero.

Maryland State Archives. “Helen B. Taussig.” Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshallfame/html/taussig.html.

National Library of Medicine. “Helen B. Taussig.” Changing the Face of Medicine. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_316.html.

National Library of Medicine. Helen Brooke Taussig, M.D., in her laboratory at Johns Hopkins, circa 1950s. U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101430102-img.

Pediatric House Calls. “Helen Brooke Taussig.” Pediatric House Calls. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://pediatric-house-calls.com/helen-brooke-taussig/.

Robays, Johan. “Helen Brooke Taussig (1898–1986): Founder of Pediatric Cardiology.” Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn 8, no. 4 (2016): 259–262. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5172576/.

Women in Medicine Magazine. “Helen B. Taussig: A Founder of Pediatric Cardiology.” Women in Medicine Magazine. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20200226010659/http://www.womeninmedicinemagazine.com/profile-of-women-in-medicine/helen-b-taussig-a-founder-of-pediatric-cardiology.

MLA — Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Helen Brooke Taussig” National Women’s History Museum, 2024. Date accessed.

Chicago — Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Helen Brooke Taussig.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/Helen-Taussig.