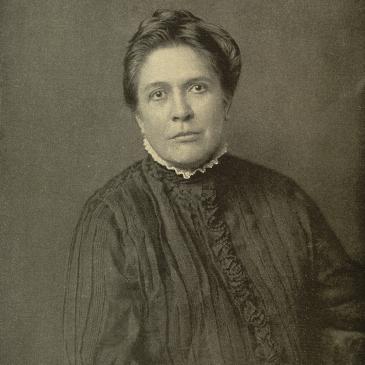

Clara Lemlich Shavelson

Lemlich Shavelson’s moving speeches, often in her native language, Yiddish, compelled many listeners to action as seen by her leadership in the Uprising of 20,000 garment workers in 1909.

Lemlich continued her activism for her entire life, breaking boundaries fighting for suffrage for working-class women and leading boycotts and the organization of housewives during the Great Depression.

“Man as a class has ruled women. He wants to make her think it is for her good he rules her, but it is too late. We are here, Senators, we are here, we are here 800,000 women in New York State alone. We have learned a good many other things. We have learned to organize together in the Industrial field. We have not learned to make good in the political field yet, but give us a chance.”

From Miss Clara Lemlich, Shirt-Waist Maker, Replies to New York Senator on Relieving Working Women of the Burdens and Responsibility of Life in 1912.

Early Years: Pushing Boundaries in the Village

Clara Lemlich was born in 1886 in the small village of Gorodok, Ukraine, into a Jewish family. In her culture, women were rarely formally educated in the way that men were, according to traditional practice. Yet, the world around her was changing. Younger Jewish people moved to larger cities for economic opportunities, opening up the shtetel for the first time to radical and revolutionary ideas. At the same time of this expanding access to political theory, antisemitic sentiments were circulating in the entire Russian empire (Orleck, Common Sense, 17-24). These ideas prohibited Lemlich from attending the only non-religious school in the village, that would have theoretically admitted young women, because they did not accept Jewish students. The Lemlich family, in retaliation to the oppression they saw and experienced, forbid Clara from studying Russian or reading Russian literature (Orleck, “Clara Lemlich Shavelson”).

To a headstrong girl determined to learn as much as she could about the world, this was only a small obstacle. She used what she already knew, offering to teach folk songs to older Jewish girls in exchange for their clandestine copies of Tolstoy, Gorky, and Turgenev. She continued to support her reading habit by sewing buttonholes on shirts or writing letters in Yiddish on behalf of her illiterate mother to send to their children who had moved abroad (Orleck, Common Sense, 20). She stored her books in the attic, where she would sit and read on a bare beam. By the time that a violent antisemitic pogrom in nearby Kishinev in 1903 gave her family the final push to leave for the United States, Lemlich was not only literate but educated in revolutionary ideas (“Life Story: Clara Lemlich Shavelson”).

Move to New York: Tenement Life and the Garment Industry

In 1905, the Lemlich family arrived in New York. Though her father was alive and able to work, sixteen-year-old Clara found work much more easily than he did as a garment worker. This was commonplace, as garment factory owners preferred to employ younger women who they believed would work for lower pay and be less likely to successfully organize into a union. Young women’s wages, while lower than men in their same field or position, were critical to family survival in the crowded tenement buildings of the Lower East Side (Orleck, Common Sense, 35).

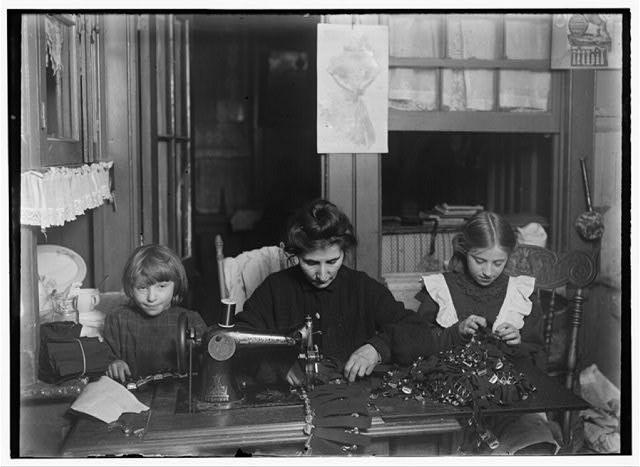

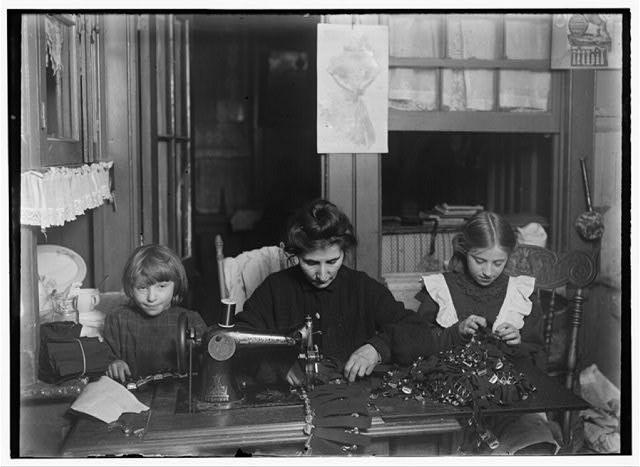

Figure 1

Family in small shop in Tenement house, N.Y.C., 1908

At an age when many non-immigrant women in New York were still in school, girls like Lemlich worked twelve- to fourteen-hour days in difficult atmospheres. Their bodies and minds took the shock of these shops: the incredible noise, the non-stop pace, and the harsh treatment at the hands of foremen (Forner and Jaffe, 125). Lemlich had worked as a seamstress from the age of 12 in her village, and in New York, she hoped to advance to a position as a garment draper where she would be guaranteed more respect and pay due to her skill (Orleck, Common Sense, 32). She was quickly disillusioned by these hopes of working through the system, and she soon turned to demanding change.

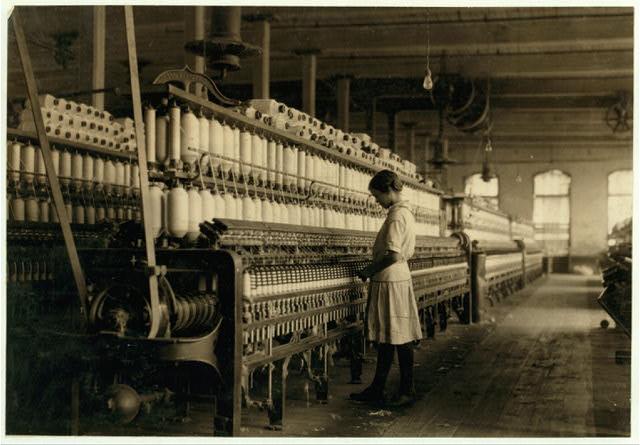

Figure 2

Fourteen-year old girl in West Texas at Brazos Valley Cotton Mill. 1913.

Union Organizing and the Uprising of 20,000

Horrified by the inhumane working conditions that she and her fellow young immigrant women experienced in the Lower East Side garment shops, Lemlich applied the revolutionary ideas and the skills for organizing people she had fostered in her home country to a new environment. She soon became a leader in the fledgling International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), which at the time of her arrival was run by older male workers. As was common in the garment industry, men such as these had more access to positions of higher pay and worked at tasks considered to be more skilled. However, this prestige on the factory floor had not garnered success in organizing young women workers, nor had the male union leaders given it much thought. Young women did not have the fortitude to maintain a general strike, they claimed, and yet Lemlich demonstrated the opposite time and time again by calling women to strike in garment shops across New York between 1907 and 1909.

In November 1909, Lemlich took the opportunity to incite one of the largest general strikes New York had ever seen. Frustrated by the lack of action being taken against the working conditions in garment factories, she insisted to be allowed to address the crowd at the New York Cooper Union meeting, saying in Yiddish:

“I am a working girl, one of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared now.”

Figure 3

Female Strikers of all classes, 1910

So began the strike of tens of thousands of young women garment workers, who all walked off their jobs over the next few weeks. Called the “Uprising of 20,000”, this was a bitter and only partially successful strike. Strikers faced violence at the hands of their employers and law enforcement, which only stopped when wealthier women known as the “mink brigade” joined their protests. Lemlich hid her bruises from her family, out of fear that they would force her to stop working if they knew the dangers she faced. As she recounted to her grandson decades afterwards:

“Like rain the blows fell on me. The gangsters hit me .... The boys and girls invented themselves how to give back what they got from the scabs, with stones and whatnot, with sticks .... Sometimes when I came home I wouldn't tell because if I would tell they wouldn't want me to go anymore. Yes, my boy, it's not easy. Unions aren't built easy.”(Orleck, Common Sense, 49).

The strike reached the goal of solidifying the ILGWU and setting off women’s strikes across the country from 1909 to 1915. However, it failed to advance the garment workers’ demands for safer working conditions (Orleck, “Clara Lemlich Shavelson”). This failure to effectively negotiate with the shops would haunt the union on March 25, 1911, when New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory killed nearly 150 workers, almost all immigrant women.

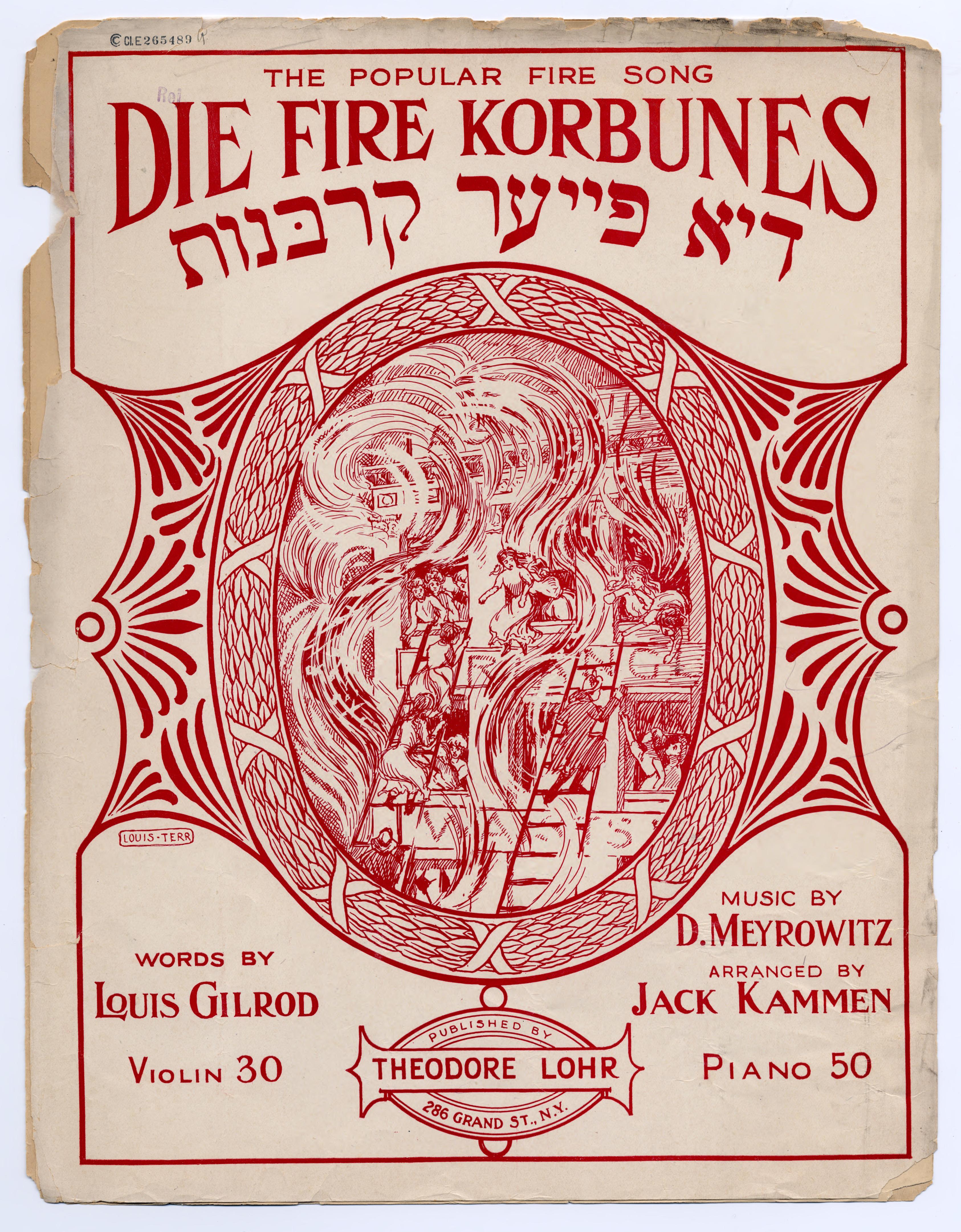

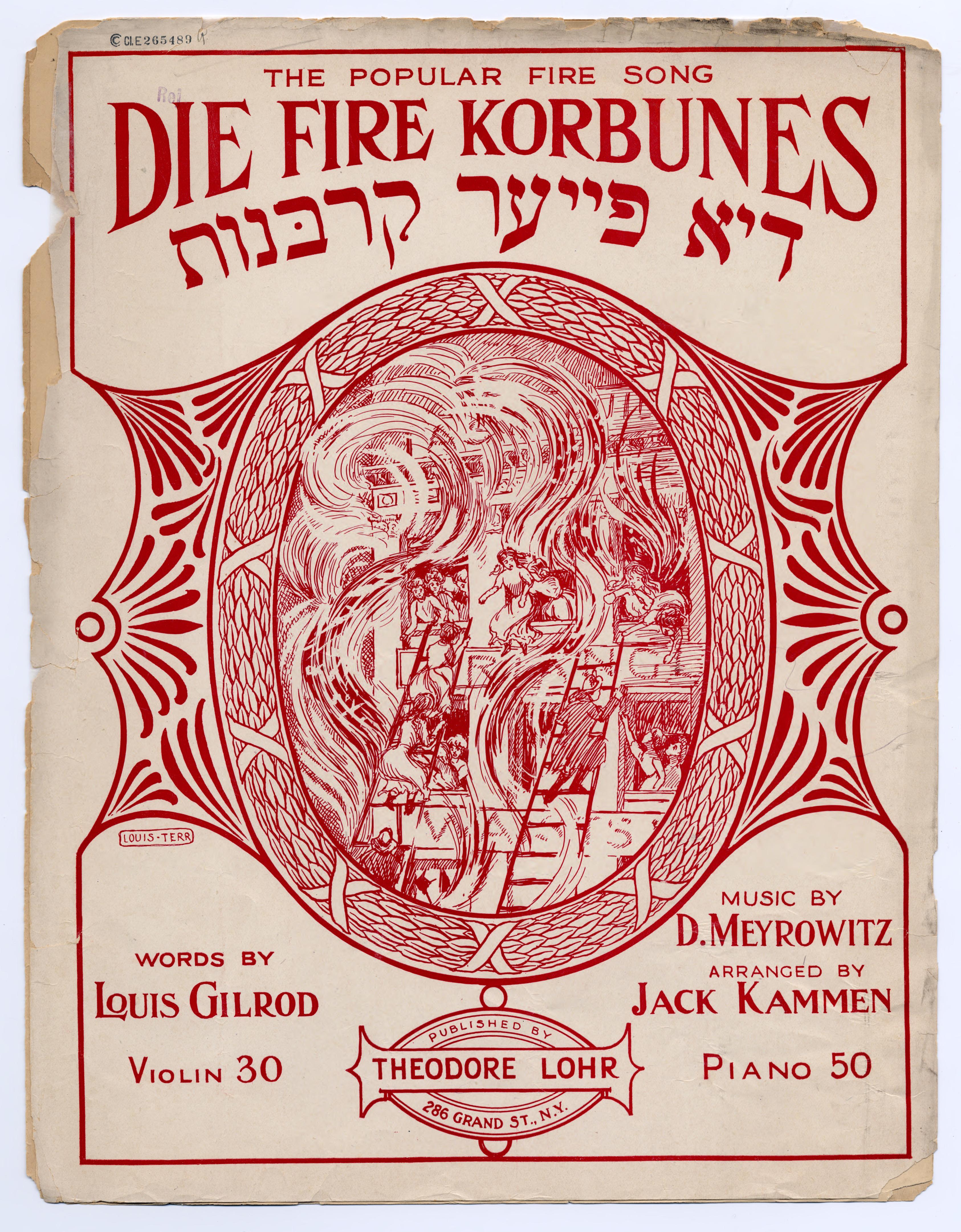

Figure 4

Die fire korbunes [The Fire Victims]. 1911.

As a result of her role in the 1909 strike and those following, Lemlich was blacklisted from the garment industry. She was able to find work only by using false names and was often caught and fired again for her union activities. Struggling financially but continuing to strive for the improvement of working women’s conditions, she turned towards the suffrage movement. Her primary aim was to convince women of her own class to see that the vote was essential to their empowerment. She reasoned,

“The manufacturer has a vote; the bosses have votes; the foremen have votes, the inspectors have votes. The working girl has no vote. When she asks to have a building in which she must work made clean and safe, the officials do not have to listen. When she asks not to work such long hours, they do not have to listen.” (Orleck, Common Sense, 91)

She argued for suffrage on street corners, in shops, and in homes to anyone who would listen, often stopping passers-by in their tracks. She created the Wage Earners League with her friends and fellow garment workers Mollie Schepps and Maggie Hinchey with the aim:

“to urge working women to understand the necessity for the vote, to agitate for the vote, and to study how to use the vote when it has been acquired.”Through their speeches and pamphlets, the league's organizers sought to give working women some quick civics lessons and to encourage their participation in the political process” (Orleck, Common Sense, 96).

On April 22, 1912, Lemlich spoke to a crowd of thousands as part of a series of speeches directed to the New York Senate at Cooper’s Union Great Hall. Among other working-class suffragist speakers, Lemlich responded with great irony about the supposed protection the Senate offered women by refusing to give them the vote:

“Man as a class has ruled women. He wants to make her think it is for her good he rules her, but it is too late. We are here, Senators, we are here, we are here 800,000 women in New York State alone. We have learned a good many other things. We have learned to organize together in the Industrial field. We have not learned to make good in the political field yet, but give us a chance.” (Lemlich, Clara. Miss Clara Lemlich, Shirt-Waist Maker, Replies to New York Senator on Relieving Working Women of the Burdens and Responsibility of Life.)

Ever fiery and refusing to back down from what she believed, at 26 she found herself out of work again after clashing with suffragist Mary Beard and being fired from her public speaking role in favor of suffragist activism. She soon married Joesph Shavelson, a printer, union man, and devoted revolutionary. They met in 1909 at a union evening school, but their courtship was slow at the beginning. They slowly got to know each other on political projects. In 1913, Joe proposed and Clara accepted – for Lemlich, because her family never approved of her politics, Joe’s family provided a sense of support and community. Joe and his two sisters had been involved in underground political activities in Russia and their vibrant stories lit up Lemlich’s fervor for action again (Orleck, Common Sense, 215).

Later Years: Housewife-Activism

The couple soon moved to out of the crowded Lower East Side to Brownsville, Brooklyn, known as a predominantly Jewish community known for activism and political engagement. There, Clara Lemlich Shavelson found a new cause: the organization of housewives around issues such as housing, food, and public education. In 1917, she led the boycott of kosher meats to protest rapid price increases, and, in 1919, she helped popularize the rent strike movement that swept New York City. In 1926, she became a member of the Communist Party and co-founded the United Council of Working-Class Housewives. This group helped wives of workers striking against unfair conditions gather food, replace wages, and provided cooperative childcare and kitchens. Shavelson’s actions were so effective that she soon moved towards the creation of the United Council of Working-Class Women, which led rent strikes, demonstrated against evictions, boycotted meat, bread, and milk, and marched on Washington. Their tactics quickly became widespread and similar strikes were held all over the country (Orleck, Common Sense, 217-240; “Clara Lemlich Shavelson,” NPS).

Clara Shavelson’s housewife activism not only helped to alleviate the effects of the Great Depression in working-class communities, but it also brought gender politics into working-class homes long before feminists of the Second Wave popularized the idea that the “personal is political.” In 1944, when her husband became ill, she returned to her garment trade roots and union organization. She, along with her husband and son, were under surveillance due to their Communist Party ties for two decades in the post-war years. Shavelson herself had her passport revoked and was once summoned to Washington to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. She was never silenced and continued to protest what she saw as unjust the rest of her life. In 1960, following the death of her husband, she married an old labor movement associate, Abe Goldman. At age eighty-one, she moved into the Jewish Home for the Aged in Los Angeles, where she helped the orderlies to create their own union. She died at home on July 12, 1982, at the age of ninety-six (Orleck, “Clara Lemlich Shavelson”).

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Family in small shop in Tenement house, N.Y.C., 1908

-

What do you notice in this environment? Does it look like a shop or more like a home? Could it be both?

-

What age do you think the woman and girls depicted are? What expressions do you see on their faces?

-

How would you feel, working all day like this? What do these girls not get to do with their time, that you do now?

Female Strikers of all classes, 1910

-

What do you notice about the women depicted?

-

Can you see any indication of their social class?

-

Their ages?

-

Their countries of origin?

-

What emotions do you see on their faces?

-

What are they striking against, and why is it important?

Die fire korbunes [The Fire Victims]. David Meyerowitz, composer; Louis Gilrod, lyricist; Jack Kammen, arranger. New York: Theodore Lohr, 1911. Yiddish American Popular Sheet Music.

-

Look at the image and then look at the words. What strikes you as unusual?

-

Why create a song about the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire?

-

How do you think this event effected the people who saw it, or heard about it?

“Clara Lemlich Shavelson.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/people/clara-lemlich-shavelson.htm

Clinton, Chelsea. She Persisted: 13 American Women Who Changed the World. New York: Philomel Books, 2017.

Foner, Eric, and Steven H. Jaffe. Activist New York: A History of People, Protest, and Politics. New York: NYU Press, 2018.

“Life Story: Clara Lemlich Shavelson. (1886-1982).” Women & The American Story. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/shavelson-clara-lemlich

Lemlich, Clara. Miss Clara Lemlich, Shirt-Waist Maker, Replies to New York Senator on Relieving Working Women of the Burdens and Responsibility of Life. New York: Wage Earners' Suffrage League, n.d. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (accessed June 4, 2025).

Orleck, Annelise. “Clara Lemlich Shavelson.” Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/shavelson-clara-lemlich

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900–1965. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Walkowitz, Daniel J., and Daniel E. Bender, eds. Social History of the United States. Vol. 4: The 1930s. 10 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2009

MLA – McKelvie, Lydia. “Clara Lemlich Shavelson.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago – McKelvie, Lydia. “Clara Lemlich Shavelson.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/clara-lemlich-shavelson.