Sonia Sanchez

Early Life and Education

Sonia Sanchez was born on September 9, 1934, in Birmingham, Alabama, as Wilsonia Benita Driver. When Sanchez was one year old, her mother, Lena Driver, died in childbirth. The family moved in with their paternal grandmother (Poets). Her grandmother’s speech and regional dialect sparked Sanchez’s passion for poetry and her fascination with language and sound. At age five, she wrote her first poem (NPR).

One year later, Sanchez’s grandmother passed away, a loss that profoundly affected her. In her grief, she developed a stutter and turned inward, immersing herself in reading and language—further sowing the seeds for her future as a poet (Black Women Radicals). Reflecting on this period, Sanchez explains, “My stutter made me a loner. And it made people ignore me. I have always been a loner. I basically stopped stuttering by the time I was in high school. Stutters are still at the base of my skull waiting to escape, waiting to catch you, but I don’t let them. I think my stutter was a form of protection that my grandmother gave to me when she died. She knew a child like me who liked to read, talk and hug and run with the wind the way I did, and stay and hide my poems, would need protection. She gave me something special (Philadelphia).”

In 1943, at the age of 10, Sonia Sanchez moved with her sister and father to Harlem, New York. There, she gradually overcame her childhood stutter and discovered the power of her poetic voice. In an interview, she explains that the family relocated because her father was organizing Black workers in the South—though he told his daughters they moved so they could receive a better education (Philadelphia). Despite that promise, Sanchez encountered discrimination in school. One teacher even told her, “I don’t know why I have to teach you anything. You’re just going to have babies.”

Determined to rise above such depleting messages, Sanchez earned her Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Hunter College in 1955. She then briefly attended New York University to pursue a graduate degree in writing, studying under poet Louise Bogan. During this time, she formed a writers’ workshop in Greenwich Village and began collaborating with major Black Arts Movement figures like Haki Madhubuti, Nikki Giovanni, and Etheridge Knight (Pennsylvania Center for the Book).

During this period, Sanchez married Albert Sanchez, with whom she had a daughter, Anita; the couple later divorced. In 1968, she married poet Etheridge Knight. They had two sons, Morani and Mungu, before eventually divorcing as well.

Teaching and the Rise of Black Studies

Sanchez began her educator journey teaching 5th grade at the Downtown Community School. Later, in her role as a professor and faculty adviser in New York City, Sanchez supported politically active Black and Puerto Rican students during a protest that led to her arrest. Although the judge offered to clear her record if she stayed out of trouble for six months, the incident resulted in her being blacklisted from teaching positions.

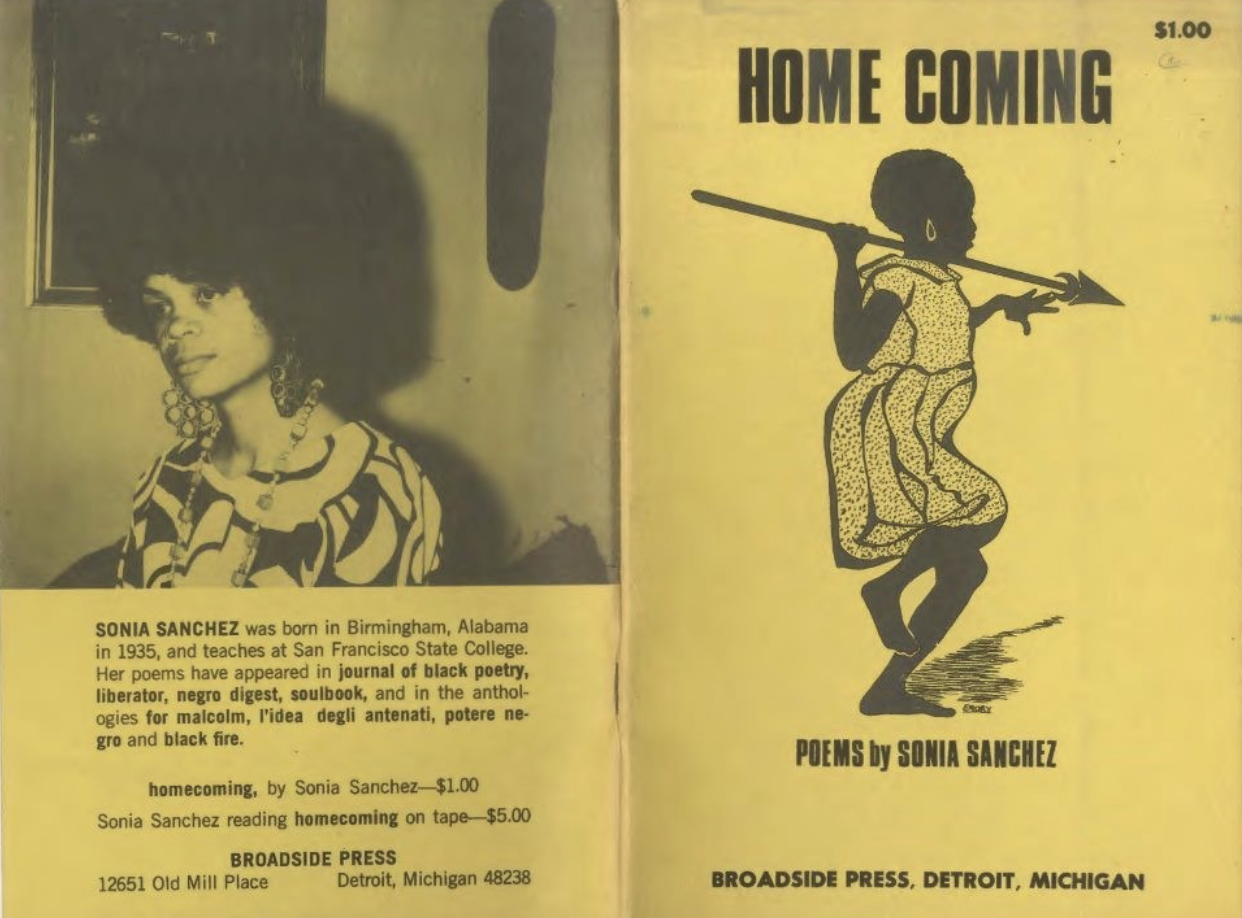

Despite her father’s warnings to avoid activism, Sonia Sanchez introduced Black Studies courses at San Francisco State University in 1968—a primarily white institution (Philadelphia). She later expanded her impact at the University of Pittsburgh, adding courses focused on Black women writers (AWBA). That same year, her first poetry collection, Homecoming, was published. The book featured African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and uniquely centered Black perspectives (Pennsylvania Center for the Book).

Over the next four decades, Sanchez lectured at more than 500 campuses and continued to teach. She became the first Presidential Fellow at Temple University, where she remained until her retirement in 1999 (AWBA).

Figure 2. The front and back matter of Sanchez’s published poems.

Activism and Revolutionary Shift

An active participant in the Civil Rights Movement, Sanchez joined the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) in the early 1960s, where she met influential civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Inspired by Malcolm X’s teachings, she shifted from integrationist views (Beliefs supporting racial integration and equal participation in all areas of society) to a focus on Black heritage and identity and became a part of the Black Power Movement (Poets).

In 1970, Sanchez published We a BaddDDD People, a collection that used poetry to illuminate the Black struggle for liberation from racial and economic oppression. She challenged traditional poetic forms and invited readers to reconsider how language could serve as a tool of resistance and liberation (Black Women Radicals).

Sanchez cites Shirley Graham DuBois—a Black radical activist, playwright, Pan-Africanist, and author—as a key influence, crediting her with introducing the concept of “international Blackness” into her thinking. “International Blackness” refers to a global awareness of the shared struggles, histories, and cultural connections among Black communities across the African diaspora.

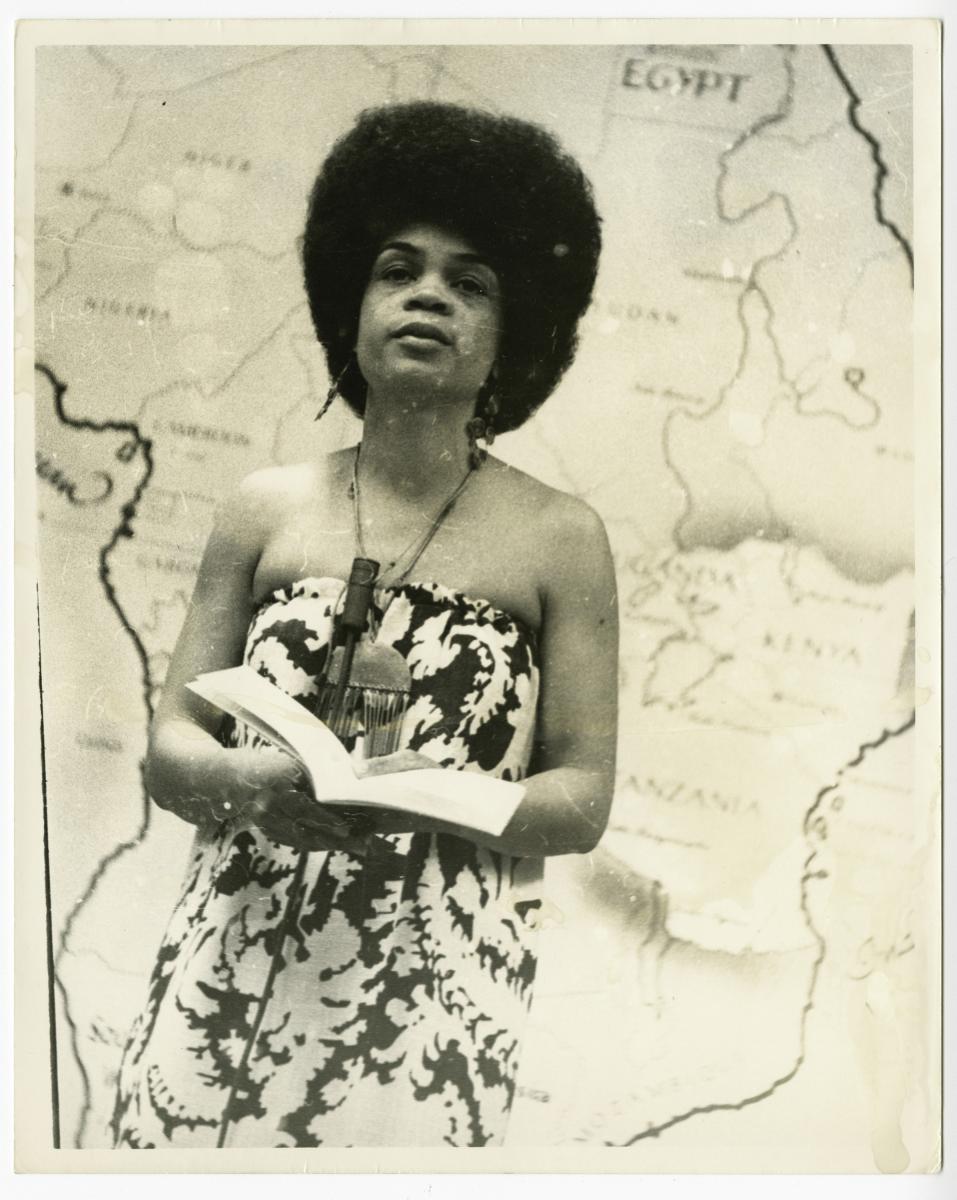

Figure 3. Photograph of Sonia Sanchez by Lloyd W. Yearwood, ca. 1960-1970. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Estate of Lloyd W. Yearwood, 2014.150.6.36.

Poetry as Political Resistance

Sonia Sanchez weaves her activism directly into her literary work. She writes poetry that confronts racism, critiques sexism within the Black community, and celebrates Black pride and power—especially in educational spaces (Pennsylvania Center for the Book). Beyond poetry, she has established herself as a playwright and children’s book author, using every form of writing as a tool for liberation.

Legacy and Continued Impact

Sanchez continues to shape culture and community far beyond the written word. In 2011, she became Philadelphia’s first Poet Laureate, using the role to elevate poetry as a force for civic engagement. Her dynamic readings and public talks serve to ignite creativity and courage in new generations of writers, thinkers, and activists.

In a 2014 TEDx Talk, she explored what it means to be human through poetry and personal reflection. She closes with a powerful call to action:

“Women and men sowing themselves onto the sleeves of change and beauty and activism and change and love and peace and peace and peace . . . it’ll get better, it’ll get better, it’ll get better because of you.”

Sanchez earned national recognition for her literary brilliance and unwavering activism. She received the American Book Award for Homegirls and Handgrenades (1985), the Robert Frost Medal (2001), the Wallace Stevens Award (2018), the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Award (2019), and, in 2021, the prestigious Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize—honoring her lifelong commitment to inspiring social change through the power of language.

Figure 4. Sonia Sanchez reads from her book Like the Singing Coming Off the Drums during an NPR Music event in 2019. Photo Credit: NPR

Author Positionality

Author Positionality

I identify as a Disabled, White passing Mexican immigrant woman. I acknowledge that my lived experiences, positionality, and the privileges I hold shape the lens through which I interpret and communicate ideas. These factors inevitably influence my writing—what I notice, what I center, and what I may unintentionally overlook. By naming this, I commit to writing with critical self-awareness, openness to feedback, and a continued effort to challenge my own biases.

Works Cited

Works Cited

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. “Sonia Sanchez.” The Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.anisfield-wolf.org/winners/sonia-sanchez/.

Associated Press. “Poet Sonia Sanchez Wins $250K Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize.” AP News, November 2, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/entertainment-sonia-sanchez-dorothy-gish-robert-frost-chinua-achebe-ee5ea0493b2beebba4cfe19f917fa629.

Black Women Radicals. “This Is Not a Small Voice: Exploring the Transformative Work of Sonia Sanchez.” Black Women Radicals, February 11, 2022. https://www.blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/this-is-not-a-small-voice-exploring-the-transformative-work-of-sonia-sanchez.

Britannica. “Sonia Sanchez.” Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sonia-Sanchez.

Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. “Sanchez, Sonia.” Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.phillymag.com/news/2021/02/20/sonia-sanchez-poetry/.

Library of Congress. “BHM 2023: Pearl Bowser Audio Visual Collection.” Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://transcription.si.edu/articles/bhm-2023-pearl-bowser-audio-visual-collection.

NPR. “Sonia Sanchez, a Force of Nature in American Poetry.” Morning Edition, November 4, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/11/04/1052098986/sonia-sanchez-poet-profile.

Pennsylvania Center for the Book. “Sonia Sanchez.” Accessed April 21, 2025. https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/bios/sanchez__sonia.

Philadelphia Magazine. “Sonia Sanchez: ‘Poetry Is a Political Act.’” Philadelphia Magazine, February 20, 2021. https://www.phillymag.com/news/2021/02/20/sonia-sanchez-poetry/.

Poets.org. “Sonia Sanchez.” Accessed April 21, 2025. https://poets.org/poet/sonia-sanchez.

Poetry Foundation. “Sonia Sanchez.” Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/sonia-sanchez.

Sanchez, Sonia. Official Website. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://soniasanchez.net/.

Temple University. “Philadelphia’s First Poet Laureate, Sonia Sanchez, Returns to Temple for a Reading.” Temple Now, October 1, 2024. https://news.temple.edu/news/2024-10-01/philadelphia-s-first-poet-laureate-sonia-sanchez-returns-temple-reading-and.

YouTube. “Black Women’s Voices Matter: Sonia Sanchez TEDxPhiladelphia.” TEDx Talks. Uploaded October 3, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DjY4pNBgMaA.

YouTube. “Poet Sonia Sanchez Performs Her Work.” PBS NewsHour. Uploaded February 7, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhJ-Cxc6cP4.

YouTube. “The Power of Poetry: Sonia Sanchez Speaks.” NPR Live Events. Uploaded March 3, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UfXwI-W1Zc4.

Classroom Resources

Classroom Resources

Classroom Resources

Bell Ringers:

-

Elementary School

-

In your journal, respond to the prompt: What is a poet? What do you think a poet does? Why might poetry be important in telling someone’s story?

-

Middle/High School

-

Sanchez used poetry to explore and celebrate Black identity and womanhood. What are some parts of your identity that are important to you? How could writing help you express them?

Additional Resources (If Applicable)

-

Homegirls and Handgrenades (1984)

-

This is Not a Small Voice (2025)

Related Biographies & Profiles

Related Biographies & Profiles

Carry the Torch

Carry the Torch

How to Cite this Page

How to Cite this Page

MLA – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Sonia Sanchez.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Sonia Sanchez.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies