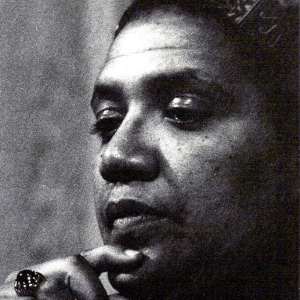

Audre Lorde

Poet and author Audre Lorde used her writing to shine light on her experience of the world as a Black lesbian woman and later, as a mother and person suffering from cancer. A prominent member of the women’s and LGBTQ rights movements, her writings called attention to the multifaceted nature of identity and the ways in which people from different walks of life could grow stronger together.

Audrey Geraldine Lorde was born on February 18, 1934 to Frederic and Linda Belmar Lorde, immigrants from Grenada. She was the youngest of three sisters and grew up in Manhattan. As a child, Lorde dropped the “y” from her first name to become Audre.

Lorde connected with poetry from a young age. She once commented, “I used to speak in poetry...when I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry.” She was around 12 or 13 at the time. She graduated from Hunter High School, where she edited the literary magazine. After an English teacher rejected one of her poems, Lorde submitted it to Seventeen magazine – it became her first professional publication.

After working a variety of jobs in New York and Connecticut, Lorde studied for a year at the National University of Mexico in Cuernavaca. It was there that she grew confident in her identity as both a lesbian and a poet. Lorde then earned her bachelor’s degree from Hunter College and a master’s degree in library science from Columbia University. She worked as a librarian in New York City public schools from 1961-1968.

In 1962, Lorde married Edwin Rollins, a white, gay man, and they had two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. Lorde and Rollins divorced in 1970.

During the 1960s, Lorde began publishing her poetry in magazines and anthologies, and also took part in the civil rights, antiwar, and women’s liberation movements. Lorde published her first volume of poems, The First Cities, in 1968. That same year, she earned a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and became the writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College, a historically Black college in Mississippi. There, she discovered her love of teaching and met Frances Clayton, a professor of psychology and her partner until 1989.

Lorde’s work was already notable for her strong expressions of African American identity, but her second anthology, Cables to Rage (1970), took on more overtly political themes, such as racism, sexism, and violence. It also included “Martha,” a poem that acknowledged her lesbianism. Her third collection, From a Land Where Other People Live (1973), was a finalist for a National Book Award for Poetry. Lorde’s work is characterized by its emphasis on matters of social and racial justice, as well as its authentic portrayal of queer sexuality and experience.

Lorde continued writing prolifically through the 1970s and 1980s, exploring the intersections of race, gender, and class, as well as examining her own identity within a global context. Her 1978 collection, The Black Unicorn, was inspired by a trip to Benin with her children. In it, she drew strength from a spiritual connection with the goddesses of African mythology. In 1982, Lorde released what she coined a “biomythography”: Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Combining elements of history, biography, and myth, it told of Lorde’s journey of self-discovery and acceptance as a Black lesbian in her childhood and young adult years. Lorde’s 1984 collection, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, included her canonical essay, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” which called on feminists to acknowledge the many differences among women and to utilize them as a source of power rather than one of division.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 1977, Lorde found that the ordeals of cancer treatment and mastectomy were shrouded in silence for women, and found them even further isolating as a Black lesbian woman. Lorde felt that the narratives of coping and healing she did encounter were designed solely for white, heterosexual women. In an effort to combat this silence and to foster connection with other lesbians and women of color facing the same struggle, Lorde offered a raw portrait of her own pain, suffering, reflection, and hope in The Cancer Journals (1980). The book won the American Library Association’s Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award for 1981 and became a classic work of illness narrative.

Lorde’s advocacy on behalf of women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community continued outside her literary career as well. In 1979, she was a prominent speaker at the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. In 1981, with Barbara Smith and several other writers, Lorde founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. Kitchen Table was devoted to promoting feminists of color and their writings. Lorde was also a founding member of Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa, an organization that advocated on behalf of women living under apartheid.

Lorde was a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Hunter College. She received many honors throughout her career including the 1990 Bill Whitehead Memorial Award and the 1991 Walt Whitman Citation of Merit, making her the Poet Laureate of the State of New York for 1991-1992. Her 1988 prose collection A Burst of Light won a Before Columbus Foundation National Book Award. Lorde earned honorary doctorates from Hunter College, Oberlin College, and Haverford College. In 2001, the Publishing Triangle association instituted the Audre Lorde Award for distinguished works of lesbian poetry. Lorde was posthumously elected to the American Poets Corner at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City in 2020.

Lorde’s cancer returned and she passed away in 1992. Shortly before her death, she participated in an African naming ceremony in which she took the name Gamba Adisa. Befitting the writer who continually explored and expressed her self-identity, it means “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known.”

Published June 2021.

Works Cited:

“Audre Lorde, 58, A Poet, Memoirist And Lecturer, Dies.” The New York Times. November 20, 1992. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/20/books/audre-lorde-58-a-poet-memoirist-and-lecturer-dies.html

“Audre Lorde.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/audre-lorde

“Audre Lorde.” Poets.org. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://poets.org/poet/audre-lorde

“Audre Lorde, New York State Poet Laureate, Dead at 58.” AP News. November 18, 1992. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/a04031e9d7cfbb38fb4af5859d3257d5

Lorde, Audre. 2018. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. Penguin Modern. London, England: Penguin Classics.

Sullivan, James D. "Lorde, Audre (1934-1992), poet, essayist, and feminist." American National Biography. Jan. 1, 2003; Accessed May 6, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1603482

Photo credit: "Audre Lorde" by K. Kendall is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/07aa8e3d-9e7d-490a-b36e-0fc622482670

How to Cite this page:

MLA – Brandman, Mariana. “Audre Lorde.” National Women’s History Museum, 2021. Date accessed.

Chicago – Brandman, Mariana. “Audre Lorde.” National Women’s History Museum. 2021. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/audre-lord

Additional Resources:

De Veaux, Alexis. Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

Audre Lorde Collection, 1950-2002. Spelman College Archives. https://www.spelman.edu/docs/archives-guides/audre-lorde-collection-finding-aid---2020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=61876f51_0

Lorde, Audre., Gay, Roxane. The Selected Works of Audre Lorde. United States: W. W. Norton, 2020.