Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was a prominent Black abolitionist and women’s rights activist best known for her powerful speeches, including "Ain't I a Woman?" which exposed how Black women were excluded from traditional notions of femininity and equality, revealing the unique oppression they faced at the intersection of race and gender.

Born into slavery in New York, she escaped to freedom in 1826 and became a key figure in the fight against slavery during the 19th century in the United States.

In 2009, Truth became the first Black woman to be represented in the U.S. Capitol with a bust.

“The truth is powerful and will prevail.”

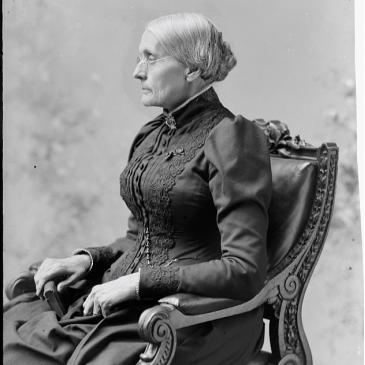

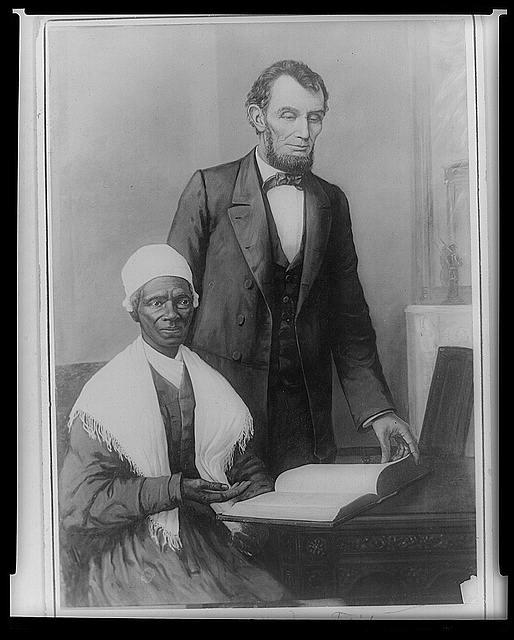

Sojourner Truth in the Book of Life, 1863

From Enslavement to Freedom

Born Isabella Bomfree in 1797 in Dutch-speaking Ulster County, New York, she grew up enslaved by multiple owners. Since records of enslaved people were rarely kept, her exact birth date remains unknown. Speaking only Dutch as a child, she never received formal education but learned Bible passages through storytelling and oral history.

Forced into labor at just five years old, Truth endured harsh conditions and was sold three times. At nine, she was separated from her parents and sold for $100, the same price as a flock of sheep. By her final sale, she was purchased for approximately $200 (Sojourner Truth Memorial). She had between ten and twelve siblings, all of whom were also sold away.

In 1815, she fell in love with Robert, an enslaved man from a neighboring farm. Their love ended tragically when Robert’s enslaver had him murdered to prevent him from fathering children he could not enslave himself. James, Truth’s first child died in childhood, likely from the harsh and inhumane conditions of his enslavement.

Truth’s final enslavers were especially cruel. Under them, Truth suffered physical abuse and was repeatedly raped, resulting in the birth of her second child, Diana. Truth was later forced into a union with another enslaved man, Thomas, with whom she had Peter, Elizabeth , and Sophia (NPS). Truth later recalled that she struggled to properly feed her babies because she was expected to nurse her enslaver’s White children instead (New York Historical Society).

The Fight for Freedom

In 1799, New York passed the Gradual Emancipation Act, a law that promised to gradually end the institution of slavery. Rather than granting immediate freedom, the act declared that children born to enslaved mothers after July 4, 1799, would be legally free at birth, but they were required to work as indentured servants for their mother’s enslaver until their mid-twenties (25 years old for females and 28 years old for males). Anyone born before July 4, 1799, would be enslaved for life. This compromise reflected Northern states moving toward abolition, while Southern states were expanding slavery to support their agricultural economy. Nearly two decades later, another piece of New York legislation set July 4, 1827, as the date when all remaining enslaved people in New York would be freed (NPS).

Gradual emancipation laws in states like New York were part of a broader shift in the early 19th century. While the North began dismantling slavery through slow, staged measures, the South doubled down on its reliance on enslaved labor to fuel its cotton economy. These contrasting approaches deepened sectional divides and set the stage for decades of conflict over slavery’s future. The delay in full freedom also meant that racial inequality persisted long after legal emancipation, shaping the lives of Black Americans who navigated a society that promised liberty but delivered it unevenly. For families like Truth’s, this meant years of waiting and uncertainty.

Truth’s enslaver initially promised to emancipate her before the 1827 deadline set by New York’s emancipation law but later reneged. Faced with the prospect of remaining enslaved despite the promise of freedom, Truth made the courageous and heart-wrenching decision to escape in 1826, a full year before the law would take effect. Truth fled with only her infant daughter, Sophia, knowing that even this act defied the law’s restrictions, which bound Sophia to years of enslavement. Truth left behind her three older children, who were still legally required to serve until their twenties. Soon after, Truth found refuge with Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen, an abolitionist family in New Paltz, New York, who purchased her freedom for twenty dollars. To mark this new chapter, she changed her last name to Isabella Van Wagenen (New York Historical Society).

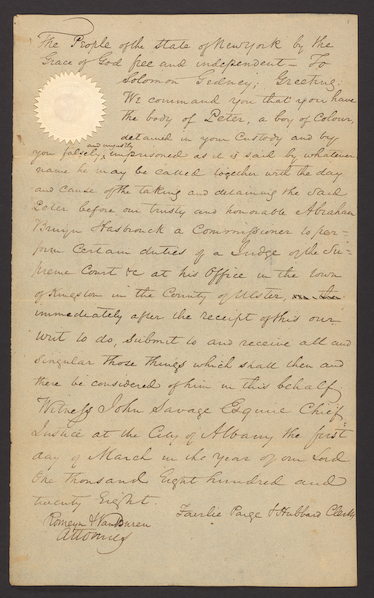

Figure 1. Records from Truth’s depositions over the Peter's Court Case.

With the support of the Van Wagenens, Truth successfully sued for the return of her five-year-old son, Peter. Shortly after her escape, her former enslaver illegally sold Peter to enslavers who took him to Alabama, despite emancipation laws requiring him to remain in New York until he turned 28. Determined to fight this injustice—one that echoed the pain she and her siblings had endured—Truth demanded that local law enforcement intervene. After a year-long legal battle, a judge of the Ulster County Courthouse ruled in her favor, making her the first Black woman to sue a White man and win (History). However, Peter’s time in the Deep South left lasting scars and trauma.

A Spiritual Awakening and New Identity

Through her advocacy for Peter’s freedom and her time with the Van Wagenens, Truth experienced a profound spiritual calling. Before this pivotal moment, she had been exposed to Dutch Reformed and Methodist teachings but had never fully embraced a religious philosophy (New York Historical Society).

In 1829, Truth and her son moved to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a preacher. In 1832, she left to work for another preacher, Robert Matthews. After Pierson was poisoned, Truth was accused of his murder but was later acquitted.

Throughout the early 1830s, she participated in the religious revivals sweeping the state, becoming a charismatic speaker. She formed connections with Black community leaders and became active in abolition, women’s rights, and pacifism. In 1839, Peter took a job on a whaling ship. Though they exchanged letters, he never returned when the ship docked three years later, and she never heard from him again.

Her growing ties to the community further strengthened her religious convictions. In 1843, she declared that the Spirit had called her to preach the truth, renaming herself Sojourner Truth.

Advocacy and Public Speaking

The following year, Truth moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, and joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry (NAEI), a progressive Abolitionist community. The NAEI’s members, including Truth and David Ruggles, were dedicated to the immediate abolition of slavery and full citizenship rights for Black Americans. The community also championed women’s rights and religious diversity.

While in Northampton, Truth met abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. As an active member of the NAEI, she was encouraged to speak publicly about the evils of slavery, solidifying her role as a powerful advocate for social justice.

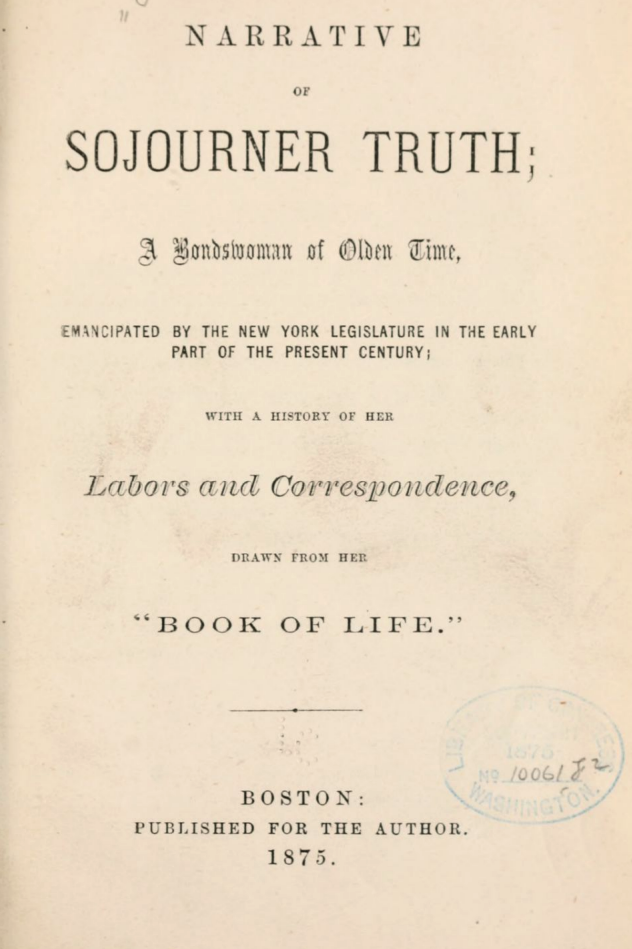

Figure 2. The cover page to The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, written by Olive Gilbert and dictated by Sojourner Truth.

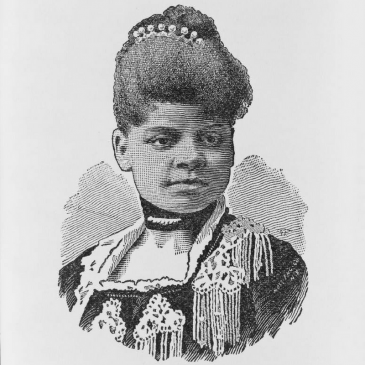

After the disbanding of the NAEI in 1850, Truth dictated what would become her autobiography—The Narrative of Sojourner Truth—to Olive Gilbert, who assisted in its publication. Her autobiography details her early years as an enslaved woman and outlines her emergence as an abolitionist and activist. The narrative details the spiritual visions that brought her to change her name and dedicate her life to preaching and activism. The autobiography ends with Truth visiting her daughter and former enslaver in New York, where he finally agrees that slavery is evil (Library of Congress). Although publishing was rare for Black women, Truth wrote her book as a means of financial survival and to amplify her voice, which ultimately brought her national recognition. She met women’s rights activists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, as well as temperance advocates—both causes she quickly championed. Through the earnings of the book, Sojourner was able to purchase a house on Park Street in Northampton (Historic Buildings of Massachusetts).

Ain’t I a Woman?

In 1851, Truth began a lecture tour that included the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, where she delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. This address became one of the most powerful statements in American history because it exposed the dual oppression faced by Black women, racism, and sexism (Smiet, 2021). Truth dismantled the notion that womanhood was synonymous with fragility and privilege, pointing out that she had endured the same physical labor and violence as men while being denied the protections afforded to White women. Her words challenged the exclusion of Black women from the women’s rights movement and forced audiences to confront how race and gender inequalities were intertwined. She exclaimed in her speech,

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

Truth’s speech demanded liberation for all women, not just white women of privilege, and exposed the hypocrisy of a society that claimed to value womanhood while denying humanity to enslaved Black women and their children. Though white editors later distorted her words to sound more Southern and misrepresented her speech patterns, her message endured as a foundational text for both feminist and civil rights movements. “Ain’t I a Woman?” is now recognized as an early articulation of intersectional feminism, demonstrating that justice cannot be achieved without addressing overlapping systems of oppression. “Ain’t I a Woman?” was later recognized as an early articulation of intersectional feminism, demonstrating that justice could not be achieved without addressing overlapping systems of oppression.

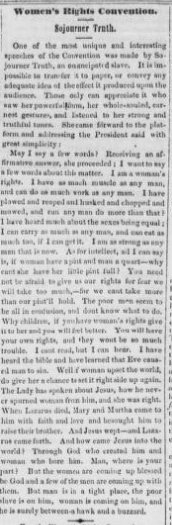

Figure 3. Clipping of Truth's Ain't I a Woman Speech in the Anti-Slavery Bugle in 1851.

Civil War and Presidential Recognition

In 1857, Truth settled in Battle Creek, Michigan, where three of her daughters lived. She continued speaking nationally and helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Truth’s advocacy efforts caught both positive and negative attention. She would face strong opposition from pro-slavery groups and was often attacked. One of these violent attacks resulted in a lifelong limp (New York Historical Society).

Figure 4. President Lincoln showing Truth the bible gifted to him by Black Baltimore community members.

When the Civil War started in 1861, Truth, who was still a pacifist, helped recruit Black young men to join the Union cause and organized supplies for Black troops, including her grandson James Caldwell, who was in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment (NPS). Truth viewed the Civil War as “a fair punishment from God for the crime of slavery,” (New York Historical Society). After the war, in 1864, Truth was honored with an invitation to the White House. While at the White House, President Lincoln showed her a Bible given to him in Baltimore by Black community members.

Truth also became involved with the National Freedmen’s Bureau Relief Association, an organization that helped formerly enslaved people find jobs and rebuild their lives (Building Knowledge Breaking Barriers). While in Washington, DC, she lobbied against segregation, and in the mid-1860s, when a streetcar conductor tried to violently block her from riding, she ensured his arrest and won her subsequent case. In the late 1860s, Truth spoke about her concern that certain civil rights leaders, like Fredrick Douglass, who prioritized the rights of Black men over those of Black women.

The Later Years

In the late 1860s, Truth advocated for land grants for freed Black Americans, though Congress never acted on her petition (NPS). She also met President Ulysses S. Grant and worked on his re-election campaign. In 1872, she attempted to vote in the presidential election but was turned away (Sojourner Truth Memorial).

Despite her declining health, Truth continued her advocacy efforts. Nearly Blind and Deaf towards the end of her life, Truth spent her final years in Michigan. Truth died on November 26, 1883, in her home at Battle Creek at the age of 86 (NPS). She was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, where her tombstone claims that she was 105 years old at the time of her passing. Her tombstone bears the question, “Is God Dead?” (History).

Figure 5. Truth’s tombstone in Battle Creek.

Her Legacy

In 1970, the State University of New York at New Paltz named their university library, the Sojourner Truth Library. 17 years later, the Sojourner Truth House was founded as a nonprofit organization who serves houseless and at-risk women and their children. In 2009, Truth became the first Black woman to be represented in the U.S. Capitol. Near her former home in Florence, Massachusetts, stands the Sojourner Truth Memorial Statue (Sojourner Truth Memorial). Numerous sculptures of Truth exist throughout the country, including in New York, California, and Michigan.

In 2024, officials held a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the new Sojourner Truth Legacy Plaza in Akron, Ohio, where Truth had delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. The plaza was designed by Summit Metro Parks landscape architect, Dion Harris, and the sculpture was made by Akron artist, Woodrow Nash.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Style: Analyzing Books and Other Printed Texas

The Narrative of Sojourner Truth

Truth’s autobiography about her earlier life as an enslaved woman who freed herself.

Primary Source Inquiry:

-

What historical events and social movements influenced the writing and publication of her autobiography?

-

Why was Truth’s narrative an important contribution to abolitionist literature? What impact do you think it had on readers at the time?

-

How does Truth describe her transformation from Isabella Baumfree to Sojourner Truth? What does this change symbolize?

-

Compare Truth’s Narrative to Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. How do their perspectives on slavery and freedom compare?

Educator Notes:

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Newspaper to guide learner inquiry.

Style: Analyzing Newspapers

Anti-slavery bugle. [volume], June 21, 1851, Page 160, Image 4

Truth writes “Women’s Rights Convention” in the Anti-Slavery Bugle after her famous speech, "Ain’t I A Woman".

Primary Source Inquiry:

-

What was the Anti-Slavery Bugle, and why was it an important platform for abolitionists and women’s rights activists?

-

What key themes does Truth emphasize in her article? How does she argue for both women’s rights and racial equality?

-

How does Truth use language and tone to persuade her audience?

-

How does Truth challenge both racism and sexism in this piece?

Educator Notes:

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts to guide learner inquiry.

Style: Analyzing Primary Sources

Caption: President Lincoln showing Truth the Bible given to him by Black Baltimore community members.

Primary Source Inquiry:

-

What is happening in this photograph? Who are the key figures, and what is the significance of their interaction?

-

Why was it significant for a formerly enslaved Black woman to meet with the President of the United States at this time?

-

What emotions or messages does the image convey?

-

Why might this moment have been important for both Truth and Lincoln?

-

What message might the photographer or the people involved have wanted to convey by documenting this meeting?

Educator notes:

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Primary Sources guide learner inquiry.

Carry The Torch

Carry The Torch

Building Knowledge Breaking Barriers (BKBB). n.d. "Annual Report: National Freedmen’s Relief Association." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://bkbbphilly.org/annual-report-national-freedmans-relief-association#:~:text=Abolitionists%20founded%20The%20National%20Freedman's,worked%20for%20the%20Treasury%20Department..

David Ruggles Center. n.d. "Northampton Association of Education and Industry." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://davidrugglescenter.org/northampton-association-education-industry/.

Fordham University. n.d. "Sojourner Truth: 'Ain’t I a Woman?'" Accessed February 20, 2025. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/sojtruth-woman.asp.

Historic Buildings of Massachusetts. n.d. "Sojourner Truth House, Northampton, Mass." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://mass.historicbuildingsct.com/?p=4942.

History. n.d. "Sojourner Truth." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/sojourner-truth.

Library of Congress. 2019. "Ain’t I a Woman? A Suffrage Story for Black History Month." February 19, 2019. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2019/02/aint-i-a-woman-a-suffrage-story-for-black-history-month/?loclr=blogser.

Library of Congress. 2021. "Sojourner Truth’s Most Famous Speech." April 6, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2021/04/sojourner-truths-most-famous-speech/#:~:text=While%20some%20of%20this%20speech's,I%20am%20a%20woman's%20rights.%E2%80%9D.

Library of Congress. n.d. "Sojourner Truth." The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/odyssey/educate/truth.html.

National Park Service (NPS). n.d. "Sojourner Truth." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/people/sojourner-truth.htm.

National Trust for Historic Preservation. n.d. "Saving Places: Sojourner Truth." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://savingplaces.org/places/sojourner-truth.

New York Historical Society. n.d. "Sojourner Truth." Women & the American Story. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://wams.nyhistory.org/a-nation-divided/antebellum/sojourner-truth/.

Slavery Monuments. n.d. "Sojourner Truth." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.slaverymonuments.org/items/browse?collection=9.

Sojourner Truth Memorial. n.d. "Sojourner Truth: Her History." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://sojournertruthmemorial.org/sojourner-truth/her-history/.

U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. n.d. "Sojourner Truth." Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/who-are-the-people-ar/sojourner-truth.

Biography photo: Sojourner Truth., ca. 1864. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/98501244/.

Image 1: New York State Archives. New York (State) Supreme Court of Judicature (Utica). Writs of Habeas Corpus, 1807-1832. J0029-82. Box 3. https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/88246.

Image 2: Gilbert, Olive, Frances W Titus, and Susan B. Anthony Collection. Narrative of Sojourner Truth; a bondswoman of olden time. Boston, For the author, 1875. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/05020876/.

Image 3: Anti-slavery bugle. [volume] (New-Lisbon, Ohio), 21 June 1851. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1851-06-21/ed-1/seq-4/

Image 4: A. Lincoln showing Sojourner Truth the Bible presented by colored people of Baltimore, Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C. , ca. 1893. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/96522312/.

Gillis, Jennifer Blizin. Sojourner Truth. Chicago, Illinois: Heinemann Library, 2006.

Library of Congress. “Today in History: November 26.” Accessed October 14, 2014.

Painter, Nell Irvin. Sojourner Truth: a Life, a Symbol. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996.

Redding, Saunders. “Sojourner Truth” in James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boyer. Notable American Women: 1607-1950, A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1971.

“This Far by Faith: Sojourner Truth.” PBS.com. Accessed October 14, 2014.

Weatherford, Doris. American Women’s History: An A to Z of People, Organizations, Issues, and Events. New York: Macmillan General Reference, 1994.

PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA — Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Sojourner Truth.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago — Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Sojourner Truth.” National Women’s History Museum. 2024 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sojourner-truth.

Website

Books/Articles

-

Bernard, Jacqueline. Journey Toward Freedom: The Story of Sojourner Truth. New York: Feminist Press, 1990.

-

David, Linda and Erlene Stetson. Glorying in Tribulation: The Lifework of Sojourner Truth. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1994.

-

Krass, Peter. Sojourner Truth. New York: Chelsea House, 1988.

-

Mabee, Carleton and Susan Mabee Newhouse. Sojourner Truth - Slave, Prophet, Legend. New York: New York University Press, 1993.

-

Ortiz, Victoria. Sojourner Truth. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1974.

-

Painter, Nell Irvin, ed. The Narrative of Sojourner Truth. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

-

So Tall Within: Sojourner Truth’s Long Walk Toward Freedom, by Gary D. Schmidt and illustrated by Daniel Minter

Women’s History Minute

Women’s History Minute: Sojourner Truth

Susan B. Anthony

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact history@womenshistory.org.

Harriet Tubman

This biography is sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University. Content created and featured in partnership with the TPS program does not indicate an endorsement by the Library of Congress.

For further information or questions, please contact history@womenshistory.org.