Alma Woodsey Thomas

Alma Woodsey Thomas was the first Black woman to have a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She was also the first Black woman to have work acquired by the White House. Her life was distinctive in other ways, too. As an artist and world traveler who never married or had children, she circumvented society’s expectations for Black women born in the 19th century.

Thomas was born on September 22, 1891 in Columbus, Georgia to John Harris Thomas, a businessman, and Amelia Cantey Thomas, a dress designer. She and her four younger sisters were born into a family that valued education and uplift. Upon earning his freedom, their maternal grandfather built a sizable farm. He sent his ten children to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. From an early age, Thomas' entire family nurtured her creativity. She initially set her sights on becoming an architect.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot created an urgency for the family to move to Washington, D.C. While their new city remained segregated, it offered secondary education for Black students. In 1907, her family moved to an Italianate row house in Logan Circle. This vibrant middle-class Black neighborhood was home to academics, artists, and business owners. Here, she became a notable figure in education, and the arts and culture ecosystem.

While at Howard University, Thomas built a creative community that influenced her trajectory. Professor James V. Herring, and her peer Loïs Mailou Jones encouraged her to experiment with abstraction. In 1924, Thomas was among the first cohort to graduate from the art program. She maintained these connections through the Little Paris Study Group.

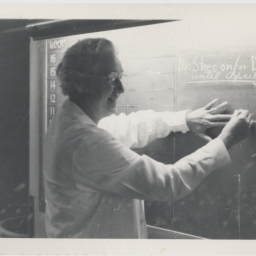

Following her graduation from Howard, she began her career as an educator at Shaw Junior High School. She taught and worked alongside fellow Howard-trained artist educators such as Malkia Roberts. Always in pursuit of learning, Thomas earned her MA from Teachers College, Columbia University where she completed a thesis entitled, The Marionette Show as a Correlating Activity in Public Schools. She honed her painting skills at local institutions, and summers in Europe. Thomas also developed a reputation for creating enrichment programs for students. She established the first art gallery in D.C. public schools in 1938. At St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, she organized the Sunday Afternoon Beauty Club. The group's field trips promoted arts appreciation and encouraged pride.

Her lifelong home in Logan Circle influenced her interpretation of the natural world. Crepe myrtle and holly trees framed the house, and Thomas maintained a garden in the backyard. Her observations of seasonal changes from her window found their way into meditative works like Wind Dancing with Spring Flowers (1969) and Wind and Crepe Myrtle Concerto (1973).

Seeing Henri Matisse's later work at the Museum of Modern Art further shaped her style. The Snail (1952) inspired her colorful Watusi (1963). She employed similar shapes and patterns. Instead of using geometric cut-outs, she used acrylic paint.

On August 28, 1963, she and her friend opera singer Lillian Evans participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The formidable demonstration pushed for civil and economic rights. Although Thomas rarely made political art, she portrayed the event in the oil painting March on Washington (1964). Her contemporaries felt compelled to speak out against white supremacy and patriarchy. They committed to work promoting Black beauty. Thomas desired to solely be an artist, rather than a Black artist or a woman artist. Her philosophy was that creativity was independent of race and gender.

In 1966, art historian James A. Porter curated Thomas’ first retrospective at Howard University’s Gallery of Art. She showed her work at the Barnett-Aden Gallery, the first Black-owned gallery in the city. The gallery championed exhibiting Black artists who had little opportunities to show elsewhere. Other local galleries like the Franz Bader Gallery also showed her work.

The Space Age ushered Thomas into a new artistic period. During this time she explored pointillism. This is a painting technique in which small dots combine to form a whole image. As she once put it, the advancement from horse and buggy to spacecraft inspired her Space series.

Most of Thomas’ recognition came in the last decade of her life. 1972, for example, was an eventful year. She had a one-woman show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. New York art curator Thomas B. Hess purchased Red Roses Sonata (1972). He later donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1976. Other high-profile collectors purchased her art for their private collections. These institutional acknowledgements did not please everyone. The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), disapproved of institutions exhibiting work by Black artists in the museum's least desirable galleries.

Following surgery at the Howard University Hospital, Thomas died on February 24, 1978. Thomas’ sister J. Maurice Thomas donated her papers to the Archives of American Art. In 1998, the Fort Wayne Museum produced her first monograph, Alma Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintings. In 2015, the White House acquired Resurrection (1966). She has received posthumous shows, including “Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful,” co-organized by the Chrysler Museum of Art in Virginia and the Columbus Museum in Georgia, on exhibit through summer 2022.

Berry, Ian, Lauren Haynes, and Alma Thomas. Alma Thomas. (New York: DelMonico Books, 2016).

“Alma Thomas.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://americanart.si.edu/artist/alma-thomas-4778.

Greenberger, Alex. “How Alma Thomas’s Radiant Paintings Plotted a New Course for Abstraction.” ARTnews. July 23, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.artnews.com/feature/alma-thomas-who-is-she-why-is-she-important-1234599867/.

Kirsh, Andrea. “The Underknown history of Alma Thomas, in print and on view.” Artblog. August 23, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021.

https://www.theartblog.org/2021/08/the-under-known-history-of-alma-thomas-in-print-and-on-view/.

Williams, Sherri. “Alma Thomas: Life in Washington.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.nga.gov/blog/alma-thomas-life-washington.html.

MLA - Brown, Aleia M. "Alma Woodsey Thomas." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2021. Date accessed.

Chicago - Brown, Aleia M. " Alma Woodsey Thomas." National Women's History Museum. 2021. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/alma-woodsey-thomas.

Photo Credit: Laura Wheeler Waring, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Alma Thomas Papers, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/AAA.thomalma.pdf.