Three Every-day Items Invented by Women

1. Liquid Paper

In 1951, Bette Nesmith Graham was a single mother working as an executive secretary at Texas Bank & Trust when she invented Liquid Paper. She and other secretaries at the bank used electric typewriters, which were becoming increasingly common in the workplace. While electric typewriters made typing easier and faster, its ribbon made correcting errors difficult. She came up with the idea to create a liquid that would allow her to paint over her mistakes, much like an artist could do by applying an additional coat. In her kitchen blender, Graham concocted a mixture of water-based tempera paint and made it match the color of the bank’s stationery. She brought the mixture into work with a thin paintbrush, began covering up her mistakes, and thought nothing of it, even though the results were so successful that her boss had no idea she was using a correcting liquid.

Eventually, other secretaries at the bank began asking Graham if they could use some of her paint mixture. She started giving the product, which she called Mistake Out at first, to them in little bottles. In 1956, Graham realized the product had enough potential for her to begin selling it. She started the Mistake Out Company and continued making and selling the mixture out of her home. In 1957, she was selling about 100 bottles of Mistake Out per month. The following year Graham was fired from the bank because she was devoting too much of her time to her company. She renamed her product Liquid Paper, received a patent for it, and was soon getting promotions in magazines and orders from large companies. With a net-worth of about $1 million, Graham built Liquid Paper’s headquarters and factory in Dallas, Texas in 1968. She sold Liquid Paper to the Gillette Corporation in 1979 for $47.5 million.

As the owner of her own company, Graham insisted Liquid Paper’s headquarters offer a childcare facility and a library, and created an environment where all employees could have a say in company decisions. She also used part of her Liquid Paper money to establish two charitable foundations that help women in need. Since her death in 1980, her son Michael Nesmith, best as one of The Monkees, has continued to contribute to Graham’s charities.

2. The dishwasher

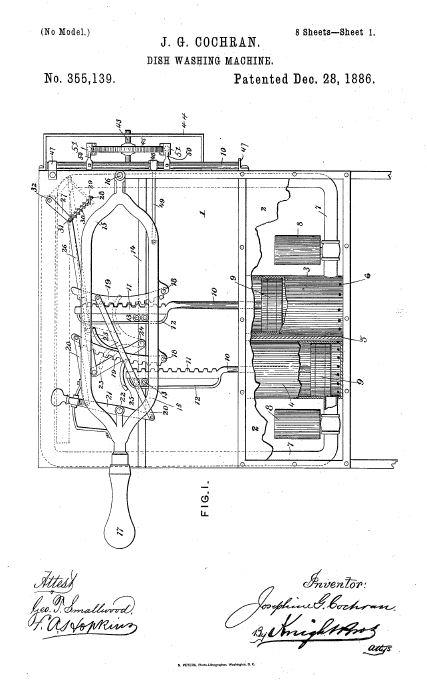

Patent number 355,139

It would be a lovely story if the dishwasher was invented by an overworked mother as a means of relieving herself and other women from the task, but that is not the case. Josephine Cochrane was a wealthy socialite who owned expensive fine china that had been in her family since the 1600s. She grew increasingly displeased with her servants when she found the china was chipping due to their supposed carelessness in scrubbing the dishes. She told them she was going to wash the dishes from then on, but found the chore to be beneath her.

Previous attempts at building a working, practical dishwasher were unsuccessful. One patented model had to be cranked by hand and the dishes inside often moved around, causing them to break. Cochrane believed she could come up with a better one and she got to work on building it. She measured all her dishes and made compartments for each that sat atop a motor-powered wheel above a boiler, which aimed jets of soapy water at the dishes so they would get cleaned. Her invention proved successful and, on December 28, 1886, Josephine Cochrane received a patent for her dish washing machine.

Josephine Cochrane on a 2013 stamp in Romania.

Cochrane presented her dishwasher at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago to great reviews and received an award for design and durability. She established a company to make and sell the dishwasher, which evolved into KitchenAid after her death in 1913. Mostly only hotels and restaurants bought the product in its first few decades of existence, though. It was not suited well for homes, in part, because residential hot water heaters at the time were not capable of producing as much hot water as was needed to run the machine. In the 1950s, advancements in technology and the beginning of the shift in women’s consciousness leading up to the Women’s Movement in the 60s and 70s, meant more dishwashers were being sold to households than ever before. They continue to be one of the most popular and desired kitchen appliances.

3. The disposable diaper

Marion Donovan spent a lifetime inventing items to make people’s lives easier. When she was in elementary school, she came up with her first invention – a tooth powder to improve dental hygiene. After graduating from college, she worked for Vogue magazine for a short time before giving up her career to be a housewife and mother. Motherhood, though, allowed Donovan to come up with her most well-known inventions.

In 1946, Donovan was taking care of her newly born second child when she came up with the idea to improve upon the diaper. Both of her children had made a habit of wetting their diapers as soon as Donovan had changed them and laid them down in their cribs. This may not sound like a major inconvenience today but in 1946, it was. Cloth diapers leaked and, when a child wet one in their crib, it required not only changing and washing the baby’s diaper as well as the sheets. There were rubber pants to put over the cloth diaper that prevented leaks, but these were known to cause diaper rash. Donovan took her shower curtain, cut it to the right size, and sewed a reusable cover for her kid’s diapers. She added snaps to close the cover, so there was no need to use safety pins like the ones that fastened cloth diapers. The cloth diapers were inserted into the waterproof covers, which kept the babies and their surroundings dry. She named the covers Boaters because she thought they looked like boats and they helped babies “stay afloat.” As an independent inventor, she manufactured and marketed her product herself until someone was willing to buy it from her, which someone did. Keko Corporation purchased Boaters from Donovan for $1 million in 1949 and began selling them in Saks Fifth Avenue later that year. They became an instant success.

After Donovan received the patent for Boaters in 1951, she set her sights on inventing the disposable paper diaper. Though her design worked, it was not a commercial success like her previous invention. Executives thought her design was an unnecessary convenience. Ten years later, Proctor and Gamble used Donovan’s invention to create Pampers, which continue to be one of the best-selling disposable diaper brands. Donovan’s other inventions include, Zippity-Do, an elastic zipper extension that made it easier for women to zip up their clothes, and Big Hangup a compact clothes hanger. At age 41, she received a degree in architecture from Yale and went on to design her own house in Connecticut