National Association of Colored Women

Black women like Sojourner Truth, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Harriet Tubman participated in women’s rights movements throughout the nineteenth century. Despite their efforts, black women as a whole were often excluded from organizations and their activities. Black female reformers understood that in addition to their sex, their race significantly affected their rights and available opportunities. White suffragists and their organizations ignored the challenges that African American women faced. They chose not to integrate issues of race into their campaigns.

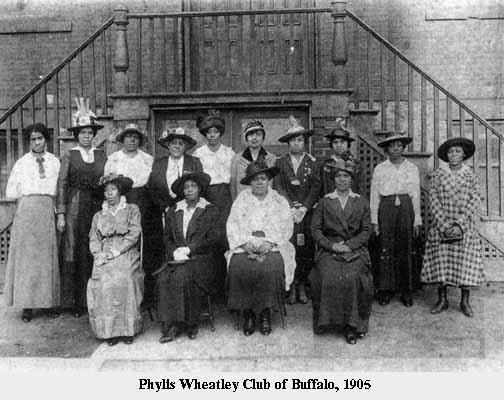

Phillis Wheatley Club, Buffalo, New York

In the 1880s, black reformers began organizing their own groups. In 1896, they founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which became the largest federation of local black women’s clubs. (While the term “Colored Women” was a respectable term in the early twentieth century, the phrase is no longer in use today.) Suffragist Mary Church Terrell became the first president of the NACW.

Suffrage was an important goal for black female reformers. Unlike predominantly white suffrage organizations, however, the NACW advocated for a wide range of reforms to improve life for African Americans. Jim Crow laws in the South enforced segregation. Blacks and whites attended separate schools, used separate drinking fountains, and even swore on separate Bibles in court. Black students had fewer opportunities to receive a good education, much less go to an elite college, than white students. Schools for African Americans often had old textbooks and dilapidated buildings. The 1896 Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson supported Jim Crow laws as long as segregated facilities were “separate but equal.” But, as the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case ruled, separate facilities were never equal.

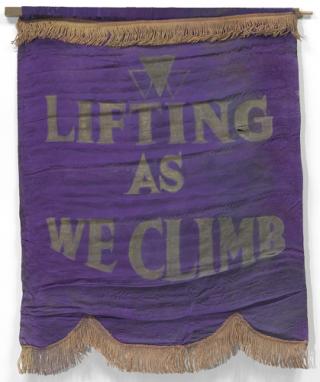

The NACW’s motto was “Lifting as We Climb.” They advocated for women’s rights as well as to “uplift” and improve the status of African Americans. For example, black men officially had won the right to vote in 1870. Since then, impossible literacy tests, high poll taxes, and grandfather clauses prevented many of them from casting their ballots. NACW suffragists wanted the vote for women and to ensure that black men could vote too.

Racism persisted even in the most socially progressive movements of the era. The National American Woman Suffrage Association, the dominant white suffrage organization, held conventions that excluded black women. Black women were forced to march separately in suffrage parades. Furthermore, the History of Woman Suffrage volumes by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in the 1880s largely overlooked the contributions of black suffragists in favor of a history that featured white suffragists. The significance of black women in the movement was overlooked in the first suffrage histories, and is often overlooked today.

By Allison Lange, Ph.D.

Fall 2015