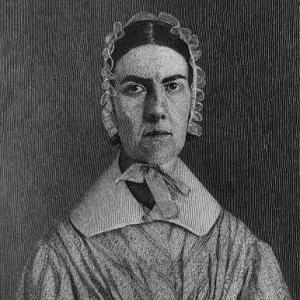

Angelina Grimké Weld

Although raised on a slave-owning plantation in South Carolina, Angelina Emily Grimké Weld grew up to become an ardent abolitionist writer and speaker, as well as a women’s rights activist. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were among the first women to speak in public against slavery, defying gender norms and risking violence in doing so. Beyond ending slavery, their mission—highly radical for the times—was to promote racial and gender equality.

Born on February 20, 1805, Weld was the last of 14 children of prominent jurist John Faucheraud Grimké and Mary Smith. The family owned a home in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, a plantation in the country, and numerous slaves. Believing women should be subordinate to men, John Grimké did not seek to educate his daughters, though his sons shared their lessons with their sisters.

Two facts—a childhood spent witnessing slavery’s cruelties and her own experiences with the limitations of gender—would shape Weld’s life and sense of mission. Early on, Weld and sister Sarah, thirteen years her senior, taught some slaves to read and held prayer meetings with others, despite their parents admonitions against it. Weld also sought to persuade her family to abandon slavery, to no avail.

Like her elder sister, Weld converted from her Episcopal religion to Quakerism, known for its relative egalitarianism and efforts to end slavery. In 1829, she joined Sarah in Philadelphia, where both became members of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Weld supported herself as a teacher, and in 1835, wrote a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist publisher who—without her consent, printed it in his newspaper The Liberator. The move launched her career as an abolitionist writer and speaker. In 1836, Weld published her pamphlet An Appeal to Christian Women of the South, urging southern women to join the antislavery movement. In South Carolina, leaders threatened Weld with imprisonment if she returned home.

Though unusual for the times, Garrison welcomed women to his American Antislavery Society, and in 1837, Weld and her sister became its first female agents, touring New York and New Jersey. Their lectures about their first-hand knowledge of slavery’s evils—especially to mixed male and female audiences—provoked rebuke from ministers for their “unwomanly behavior.” Such reactions drew both women into the women’s rights debate, with Weld authoring a series of letters in The Liberator. Undeterred, Weld became the first woman to address the Massachusetts State Legislature in February 1828, bringing a petition signed by 20,000 women seeking to end slavery.

Through the AASS, Weld met Theodore Dwight Weld, a leading agent for Garrison’s abolitionist group. The pair married in 1838 and two days later, Angelina spoke at the annual antislavery convention in Philadelphia. Later that night, angry crowds burned the building to the ground.

The Welds retired from speaking but continued to attend antislavery meetings and write abolitionist tracts, including American Slavery As It Is (1839). The couple moved with Sarah—who remained with them throughout her life—to New Jersey, where they bought a farm and the sisters made a living as teachers. Angelina had three children: Charles Stuart (1839), Theodore Grimké (1841) and Sarah Grimké Weld (1844). The family moved in 1864 to Hyde Park, Massachusetts, where in 1870, the two sisters attempted to vote in a local election.

-

Berkin, Carol. “Angelina and Sarah Grimké: Abolitionist Sisters.” History Now: American History Online.

-

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed April 12, 2015.

-

Berkin, Carol. Civil War Wives: The Lives and Times of Angelina Grimké Wed, Nina Howell Davis & Julia Dent Grant. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

-

Fladeland, Betty L. “Grimké, Sara Moor (Nov. 26, 1792-Dec. 23, 1873) and Angelina Emily (Feb. 20, 1805-Oct. 26, 1879)” in James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boyer, eds. Notable American Women: 1607-1950, A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1971.

-

Lerner, Gilda. The Grimké Sisters from North Carolina: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

-

PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA - Michals, Debra. "Angelina Grimke Weld." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2015. Date accessed.

Chicago - Michals, Debra. "Angelina Grimke Weld." National Women's History Museum. 2015. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/angelina-grimke-weld.

-

http://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/Grimké-sisters.htm

-

“Southern Abolitionist Angelina Grimké | The Abolitionists”. American Experience (video).

-

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=285

Books:

-

Grimké, Angelina Emily. Appeal to Christian Women of the South. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836.

-

Todras, Ellen. Angelina Grimké: Voice of Abolition. (Juvenile Nonfiction) New York: Linnet, 1999.