Mary Putnam Jacobi

Mary Putnam Jacobi was a groundbreaking doctor and holder of many “first woman” titles, including the first woman to hold a pharmacy degree in the U.S. and to be admitted to the École de Médecine of the University of Paris.

She was an early proponent of proper scientific research in medical research in the U.S. and conducted a major study dispelling myths about menstruation.

She fought for gender equality, particularly in education and suffrage.

“Unknown things want science to make them known.”

Mary Putnam Jacobi, Theorae ad lienis officium (“Theory on the Function of the Spleen”)

Early Life

Born August 31, 1842 in London to American parents, she grew up in New York City as the eldest of 11 children of the publisher George Palmer Putnam. From a young age, her father’s business and social circles brought her into contact with the likes of Edgar Allan Poe, Washington Irving and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. When she was 12, her father published Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell’s first book, The Laws of Life; although he reflected attitudes of the day that medicine was not a proper profession for women, he supported her views on hygiene and public health. Dr Blackwell was the first woman in the United States to receive a medical degree, and would prove a valuable mentor for Putnam. At 17, Putnam was allowed to begin working for Dr. Blackwell at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, despite her father’s concerns that pursuing this supposedly masculine profession would lead her to be infertile. The Infirmary and the school that it later expanded to include were run by Drs. Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell continued to lead the organization after Elizabeth returned to the U.K. permanently. In June 1863, during the U.S. Civil War, she travelled to New Orleans, initially to find and care for her brother, Haven, whom the family had learned had contracted malaria. But by the time she reached him, the young man had recovered. Putnam stayed in Louisiana for a few months, volunteering at the local hospital and the Freedman’s Commission—which provided education, medical care and other support for formerly enslaved people—before returning north.

Education and Early Career

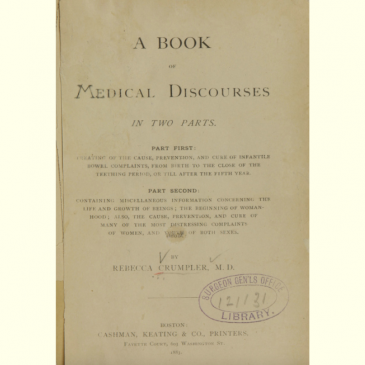

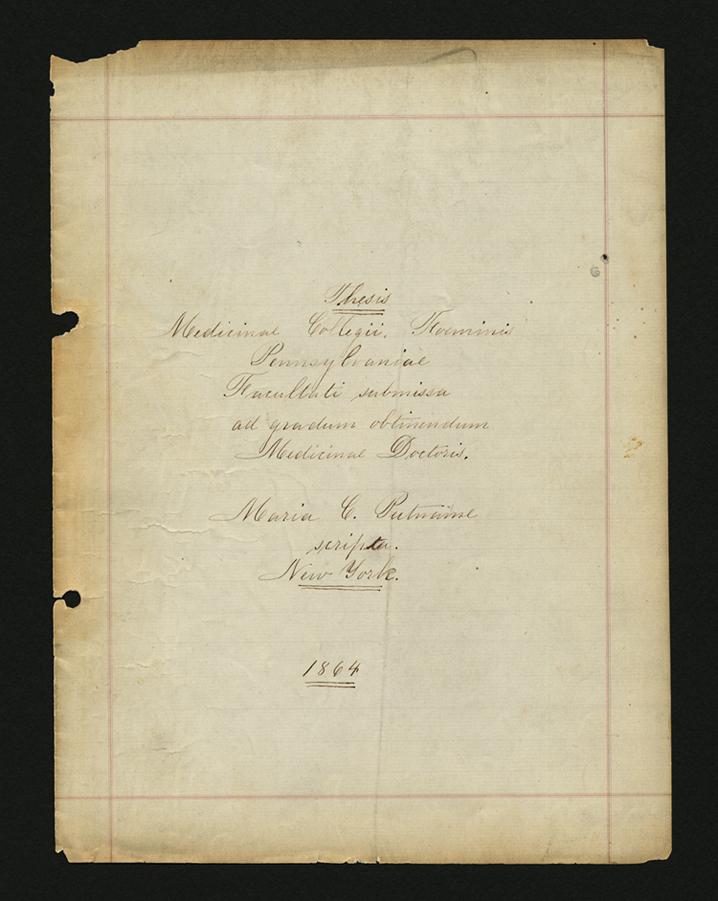

At age 21, Mary Putnam became the first woman in the United States to earn a degree in pharmacy when she graduated from the New York College of Pharmacy. Putnam went on to earn her doctor of medicine from the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, the first fully accredited women's medical college in the country, in 1864.

Figure 1. Mary Putnam’s Thesis at New York College, Drexel University, Legacy Center.

While there, her father wrote to her,

“you know very well that I am proud of your abilities and am willing that you should apply them even to the repulsive pursuit (for it is so in spite of oneself) of Medical Science. But don’t let yourself be absorbed and gobbled up in that branch of the animal kingdom ordinarily called strong minded women! Don’t let them intensify your self-will and independence for they are strong enough already. Don't be congealed or fossilized into a hard, tenacious, unbending personification, of intellectual conceit, however strongly fortified you feel sure that you are… I do hope and trust you will preserve your feminine character and, with all your other studies, study a little the proprieties and elegancies of life. Be a lady from the dotting of your i’s to the color of your ribbons-and if you must be a doctor and a philosopher, be an attractive and agreeable one.”

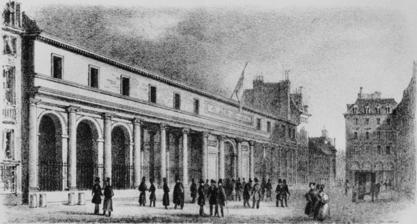

Medical and pharmacy degrees in hand, Putnam set her sights on France—more specifically, the École de Médecine of the University of Paris, which at the time did not admit women. With Dr. Blackwell’s support, she was able to begin working in clinics in the city, expanding her professional networks and reputation. Biographer Lydia Reeder notes,

“she ended up working in some of the finest laboratories in Paris and for some of the greatest research scientists in the world. It was interesting because she was so intelligent and yet so small and so feminine, instructors began competing to see who could obtain the next connection for Mary to gain admittance to some clinic. The more clinics she got into, the more chance she had for being admitted to the medical school. Professors fell in love with her intelligence. It was interesting, she made them want to teach her and I found that to be an unequaled achievement for a woman back then.”

Putnam became the first female student accepted into the school in 1868, and the second woman to graduate in 1871, despite the 1870 siege of Paris by the Prussians.

Figure 2. École de Médecine in Paris, Changing the Face of Medicine.

Between her degrees and clinical experience, Putnam returned to the United States arguably one of the most educated physicians of any gender in the country. She began teaching at the medical school for women connected to the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Recognizing the biases against such institutions, however, she organized the Association for the Advancement of the Medical Education of Women in 1874 to advocate for women’s acceptance into mainstream medical schools, and served as president until 1903.

In 1873, she married the twice-widowed Abraham Jacobi, a prominent children’s physician 12 years her senior who became known as the “father of American pediatrics.” Contrary to her father’s concerns, she would go on to have three children, though only her daughter Marjorie (born 1878) survived to adulthood. Unfortunately, her father would not see his eldest daughter married, as he died in 1872; Putnam was still wearing mourning black at her simple courthouse wedding.

Menstruation and Misinformation

At this time, there were almost 2,500 female doctors in the United States, with women-run hospitals across the country. Naturally, women patients often preferred to see these doctors, sparking resentment among male physicians who considered themselves—and were considered by others—to be experts in women’s health. Many of these men believed, and promoted, ideas that women were unfit to hold any job other than teaching and nursing. They published so-called “scientific papers” in which they claimed, with no evidence, that women were biologically incapable of pursuing higher education because menstruation made them constantly sick and emotionally unstable. The most prominent such work was arguably the 1873 book Sex in Education or a Fair Chance for the Girls, by Harvard professor Dr. Edward Clark, who argued that girls never be allowed to study more than four hours per day, separate from boys, and take every fourth week off entirely lest they become infertile and even devolve into a theoretical third gender that he called “agene” and compared to sexless termites. It became an international bestseller.

Putnam’s education in Paris extended beyond the classroom and clinic, into the laboratory as well. In a time where medical research as we know it today was still in its infancy, Putnam was one of a relatively small number of medical professionals engaging in methodical, scientific research. As such, she seemed the perfect candidate to rebut such baseless claims with actual science. Putnam was one of several prominent activists and scientists to respond to Clark’s book, utterly dismantling his arguments and illustrating his fallacies with her essay Mental Action and Physical Health in The Education of American Girls, a collection published by her father’s company in 1874. Her essay and the exuberant reviews it elicited brought her to a new height of recognition as both a doctor and advocate for women’s education.

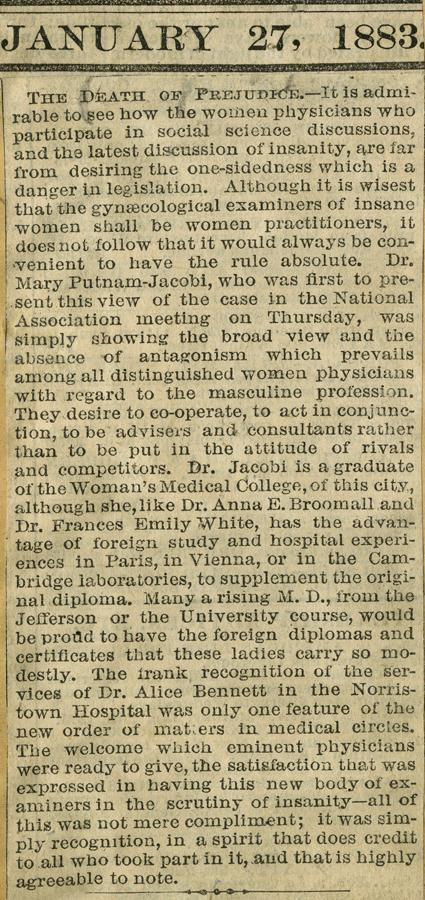

At the time, the Harvard Boylston Medical Society comprised Boston’s medical elite, and each year these top male physicians hosted a competition, where doctors were given two years’ advance notice of a topic on which to submit essays. In 1874, the society announced that the subject for the 1876 prize would be whether women require mental and bodily rest during menstruation, and to what extent? It was a hotly debated issue – the book featuring Putnam’s essay was one of four published that year to counteract Clark’s, among the various other writings on both sides. It also reflected growing discussion around women’s rights more broadly in the country—suffragists, for example, recognized that if women couldn’t be trusted to be educated, they also couldn’t be trusted to vote. Apart from Putnam’s qualifications, the essays for the Boylston Prize were judged anonymously, increasing her chances of winning.

When the topic was announced, Putnam was pregnant with her second child and initially declined when other women’s rights activists asked her to take on the challenge. She also believed that even if her essay was chosen, she would be disqualified once the committee of Harvard professors judging the contest discovered she was a woman. Although she was eventually persuaded, she did not have the full two years to conduct her research. But with the help of a vast network of influential women’s rights advocates and organizations, she did something innovative for her time—a survey. She created a questionnaire and volunteers made and distributed a thousand copies, then retrieved and returned the completed versions to her. Unlike Clark’s anecdotal and biased “evidence,” Putnam’s study reflected hundreds of women: rich and poor, rural and urban, of different education levels and occupations.

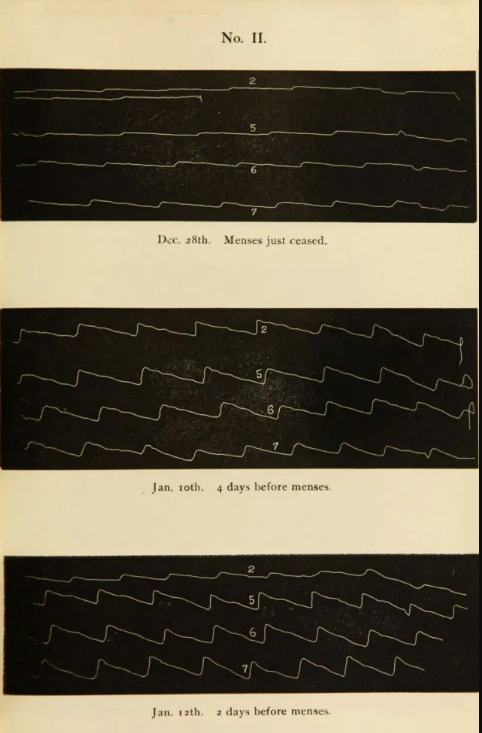

This was in addition to experiments conducted with her colleagues from the New York Infirmary for the Women and Children aiming to map the physiological and chemical signs of menstruation. This encompassed everything from blood and urine tests to having patients use exercise machines to tracking body temperatures at different stages. The last of these led to the discovery that ovulation could be indicated by these temperature changes, leading to the rhythm method for natural family planning in the 1930s.

She brought all of this information together in a clear, detailed paper and, in 1876, Putnam became the first woman to win the Boylston Prize with her essay The Question of Rest During Menstruation. Because the committee did not publish winning essays, she adapted it for a public audience and her father’s company published this version the following year.

Figure 3. Dr. Mary Putnam’s measurements of the pulse by a sphygmograph, National Library of Medicine.

Expanding Her Work

While the Boylston Prize was a great achievement for both Putnam herself and the women’s rights movements more broadly, she was only in her mid-30s at the time, with decades more before her for research, activism and treating patients. She went on to study neurology, dismissing arguments that women’s physically smaller brains had anything to do with intelligence or capacity for learning. She became a professor at the Post-Graduate Medical School, lecturing on childhood diseases to male and female physicians alike, albeit for no pay. She also wrote extensively, challenging the gender binary and presumed clear divisions defining manhood and womanhood. She also continued to mentor young women physicians, promote public health and fight for equality in education as well as other women’s rights issues like suffrage. In 1880, she became the first woman admitted as a fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Unfortunately, as her professional success was unparalleled, her once-happy marriage began to deteriorate. Her husband had been a political activist who worked with the likes of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in his younger years, and later a very progressive doctor in matters like contraception. The two had actually met after he actively supported Putnam’s membership as one of the first women in the New York State Medical Society when he was president. Yet after the birth of their second daughter, Marjorie, in 1878, Abraham Jacobi began unsuccessfully pushing his wife to stay home and raise their two children. Between his previous two marriages, he had already lost five children before their first daughter died shortly after her birth. Their son Ernst, born during Putnam’s Boylston research, would die of diphtheria when he was just seven years old.

Having trained in medicine almost 20 years apart, Putnam also valued medical research and evidence-based practice much more than her husband. Where she embraced new information about topics like bacteria, he scoffed at what he called “bacteria mania.” When Ernst fell sick, Putnam deferred to her husband’s recommended course of treatment over her own preferences. She later came to believe that, had she done more to challenge Jacobi’s authority, their son would have lived. Meanwhile, he resented her career success, claiming her busy schedule was somehow to blame despite her attentiveness during Ernst’s illness. He blamed the children’s favorite nurse and sent her away, yet it is more likely that Jacobi himself brought the bacteria home – like many male doctors of the time, he disregarded the hygiene practices that are standard today, like handwashing and changing out of potentially contaminated clothing. The discovery of the bacteria that causes diphtheria, just months after Ernst’s deaths, deepened the rift between the spouses. Nevertheless, the couple remained married until her death in 1906.

While Jacobi was lost to his grief, Putnam openly talked about hers and was able to channel her energies into caring for her daughter and adding suffrage to her advocacy, where previously she had disregarded the cause in favor of women’s education. She expanded her work to include labor reform, conducting sociological surveys of shop girls and publicizing which stores treated their female workers well – and which did not. Education did not fall by the wayside, however—she was part of a committee of women who raised over $100,000 to fund the Johns Hopkins medical school and force school administrators to make it co-educational from its opening in 1893 as the country’s first graduate school of medicine, and the first to admit women on equal terms as men.

Figure 4. News clipping declaring the end of prejudice against women in medicine, citing Mary Putnam, Drexel University.

Not long after becoming a grandmother, Putnam began experiencing episodes of piercing pain in her head, accompanied by hand tremors and nausea that left her debilitated. Ever the scientist, Putnam began documenting her symptoms and eventually diagnosed herself with a brain tumor. Her final paper was Descriptions of the Early Symptoms of the Meningeal Tumor Compressing the Cerebellum. From Which the Writer Died. Written by Herself.

Legacy for Women and Girls Today

Jacobi earned a place for herself in history from the early years of her career as a woman of “firsts,” but it is the work she did throughout her career as both a scientist and an activist that continues to impact women and girls in today’s world. Even in the 21st century, period stigma remains an issue and menstrual myths persist, but she laid the groundwork for the scientific refutation of these ideas. Beyond that, she helped to usher in an era of medical research to replace the pseudoscience that had prevailed in the United States for centuries, based more in bigotries than in realities. The ripple effects of her mentorship can be seen in the work of her students, like Dr Anna Wessels Williams, whose work was instrumental in developing an antitoxin for diphtheria. By helping to push for Johns Hopkins’s medical school to be coeducational from its inception, she helped shape gender equity in med schools for generations to come. The beneficiaries of her work are not just the many women doctors and medical researchers who followed the trail she blazed, but all of the patients who have benefited from their care and discoveries.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

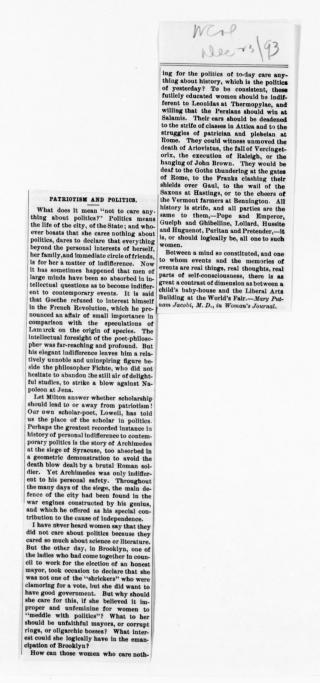

Textual Analysis

National American Woman Suffrage Association Records: General Correspondence.

Observe

- Based on how the text is organized, what type of printed material do you think this is?

-

What words or phrases stand out to you?

-

What topics or ideas seem to be discussed in the article?

Reflect

-

What might this article reveal about how women’s roles in politics were viewed in the 1890s?

-

How does Dr. Jacobi connect the ideas of patriotism, politics, and education?

-

How might readers at the time have reacted to Jacobi’s argument?

Question

-

What impact might writings like this have had on public opinion about women and politics?

-

How might the meaning of “patriotism and politics” differ today?

-

What could have motivated Mary Putnam Jacobi to write this piece?

Lydia Reeder, The Cure for Women: Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi and the Challenge to Victorian Medicine That Changed Women’s Lives Forever (St. Martin's Press, 2024).

Mary Putnam Jacobi, Life and letters of Mary Putnam Jacobi (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1925).

Lydia Reeder, Lydia Reeder on Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, interview by Allison Tyra, Infinite Women podcast, August 11 2025.

Transcript: https://www.infinite-women.com/wp-content/uploads/Lydia-Reeder-on-Dr.-Mary-Putnam-Jacobi-transcript.pdf

MLA — Tyra, A. “Mary Putnam Jacobi” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago —Tyra, A. “Mary Putnam Jacobi” National Women’s History Museum. 2025. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/Gertrude-Elion