Frances Perkins

Perkins played a central role in crafting and implementing major New Deal policies, including Social Security, minimum wage laws, and labor protections.

Perkins's work was shaped by her lifelong advocacy for workers' rights, women's suffrage, and progressive reform during a period of enormous social and economic upheaval in the United States.

“The people are what matter to government, and a government should aim to give all the people under its jurisdiction the best possible life.”

- Frances Perkins (1965) in Two views of American Labor

Early Life and Education

Frances Perkins was born Fannie Coralie Perkins on April 10, 1880, in Boston, Massachusetts. Two years later, her father moved the family to Worcester, where he owned a stationery business (Frances Perkins Center). Despite the distance, Frances spent her childhood summers at the family farm in Newcastle, affectionally known as The Brick House, with her paternal grandmother and her grandmother. During the winters, her grandmother and uncle would stay with the family in Worcester. Perkins’s family and deep-rooted heritage, traced back to early American colonization, which shaped her identity and instilled in her a strong sense of ancestral pride. Reflecting on her upbringing, Perkins once said, “I am extraordinarily the product of my grandmother” (Frances Perkins Center).

Perkins grew up in a strict, conservative, Republican household. Her father took an active role in the education of Perkins and her sister Ethel, beginning with Greek readings and grammar lessons when they were just eight years old. He later enrolled Perkins at Worcester Classical High School (Columbia).

Figure 1, Portrait of Frances Perkins as a child. Image credit to Frances Perkins Center.

After high school, Perkins attended Mount Holyoke College from 1898 to 1902. There, she served as vice president and later president of her class. After graduation, she was named permanent class president (Columbia). Perkins majored in physics with minors in chemistry and biology, but it was a required course in American economic history that shifted her trajectory (Frances Perkins Center).

The course, taught by Annah May Soule, included visits to nearby mills. These visits, combined with readings like Jacob Riis (1890), How the Other Half Lives, and a speech by Florance Kelley sparked her lifelong commitment to social reform (Columbia). Reflecting on this period, Perkins later said:

“From the time I was in college I was horrified at the work that many women and children had to do in factories. There were absolutely no effective laws that regulated the number of hours they were permitted to work. There were no provisions which guarded their health nor adequately looked after their compensation in case of injury. Those things seemed very wrong. I was young and was inspired with the idea of reforming, or at least doing what I could, to help change those abuses,” (Frances Perkins Center).

After graduating, Perkins’s parents hoped she would pursue teaching and marriage. She taught high school science in Worcester briefly, then moved to Lake Forest, Illinois, to teach at Ferry Hall, an all-girls school. While there, she diverged from her parents' expectations by changing her name and converting to the Episcopal faith, a decision that profoundly influenced her sense of public duty (Frances Perkins Center).

From Settlement Houses to State Government

Perkins shifted into social work after teaching. She worked at two settlement houses in Chicago: Hull House, with Jane Addams, and Chicago Commons. In 1907, she moved to Philadelphia (FDR Library). There, she worked with the Philadelphia Research and Protective Association, which supported immigrant girls, including Black women from the South (Columbia). During this time, she studied sociology and economics at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1909, Perkins moved to New York City. She completed a fellowship at the New York School of Philanthropy (Frances Perkins Center). Also, while in New York, she earned a master’s degree in economics and sociology from Columbia University in 1913 (AFL-CIO).

In 1910, Perkins became Executive Secretary of the New York City Consumers League, working closely with Florence Kelley (Frances Perkins Center). One year later, Perkins witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire , a tragedy that killed 146 young immigrant women who were trapped behind locked doors. Deeply affected, she became the chief investigator for the New York State Factory Investigating Commission (White House). Her efforts led to the passage of 33 new labor laws in New York, including regulations on fire safety, building codes, and working hours (GovInfo).

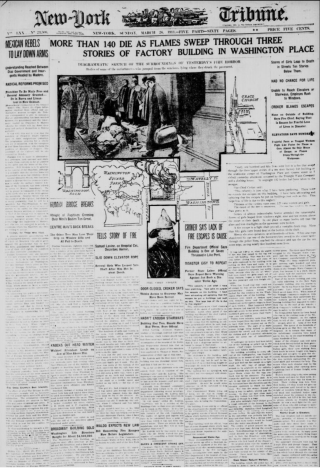

Figure 2, Image of New York Tribune article covering the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Image from the Library of Congress.

In 1919, Governor Alfred E. Smith appointed Perkins to the New York State Industrial Commission. She joined the State Industrial Board in 1923 and became chairperson in 1926 (Britannica). After the 1929 stock market crash, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her chair of the New York State Industrial Commission (FDR Library).

First Woman in the U.S. Cabinet

In 1933, President Roosevelt appointed Perkins as Secretary of Labor, making her the first woman in U.S. history to serve in a presidential Cabinet. She served in this role for 12 years (Social Security). At her nomination meeting, she made her acceptance conditional on Roosevelt’s support for a sweeping social reform agenda (Harvard). Her proposals included national unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, a federal minimum wage, a maximum-hour workweek, a ban on child labor, and a social security system (Harvard).

Figure 3, Perkins on the cover of Time magazine in 1933. Cover credit to Time and image credit to Ullstein Bild/Getty

Once Roosevelt agreed, Perkins became a principal architect of the New Deal (Time). She played a key role in developing the Social Security Act of 1935, which created retirement pensions for workers, unemployment insurance, and workers' compensation for job-related injuries (Women’s History). Perkins also oversaw major New Deal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Public Works Administration (PWA), which provided jobs to millions. Additionally, she fought to end child labor, expand workers' rights, and ensure the passage of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which codified the right to collective bargaining (Frances Perkins Center).

Figure 4, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs a bill, June 6, 1933. Standing behind him, from left, are: Rep. Theodore A. Peyser, D-N.Y., Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, and Sen. Robert Wagner, D-N.Y Image from AP.

Navigating Gender and Power

Perkins’s role in the Cabinet was often controversial as her male colleagues viewed her to be an outsider and distrusted her progressive ideas. The press frequently scrutinized her--not for her policies, but for her appearance and reserved demeanor. She famously took notes on male colleagues’ comments, filing them under a red envelope labeled “Notes on the Male Mind” (NPR). Despite these challenges, she remained composed and often credited Roosevelt and others for her work, avoiding self-promotion.

Figure 5, Roosevelt’s Cabinet, 1933. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

Private Life

Perkins rarely discussed her personal life publicly. She married Paul Caldwell Wilson in 1913 but chose to keep her surname, valuing her professional identity (Frances Perkins Center). In 1915, she discovered Wilson’s extramarital affair but chose to stay in the marriage. Perkins experienced three pregnancies, but only one child, Susanna Perkins Wilson, survived, born on December 30, 1916. While the marriage stabilized for a time, Wilson later faced mental health struggles as well and became estranged from her mother (Frances Perkins Center).

Later Years and Legacy

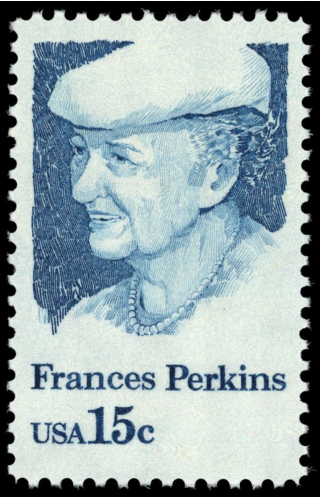

After Roosevelt’s death in 1945, President Truman appointed Perkins to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, where she served until 1953 (AFL-CIO). She later taught at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations and published her memoir, The Roosevelt I Knew, in 1946. Perkins died on May 14, 1965, in New York City at the age of 85. Though not always as publicly celebrated as her male counterparts, her legacy endures in the policies that reshaped American labor and social welfare. She has been honored with a U.S. Department of Labor building named after her, a national monument, a postage stamp, and induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame (1982).

Figure 6, Frances Perkins postage stamp issues in 1980. Credit to the National Postal Museum.

Works Cited

Works Cited

AFL-CIO. “Frances Perkins.” AFL-CIO. https://aflcio.org/about/history/labor-history-people/frances-perkins.

Brennan, Elizabeth. “Frances Perkins: The Woman Behind the New Deal.” NPR, April 16, 2009. https://www.npr.org/2009/04/16/102959041/frances-perkins-the-woman-behind-the-new-deal.

Britannica. “Frances Perkins.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frances-Perkins.

Columbia University Libraries. “Early Years and Family.” Frances Perkins: A Life at Columbia University. https://exhibitions.library.columbia.edu/exhibits/show/perkins/early-years---family.

FDR Library. “Frances Perkins.” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/perkins.

Frances Perkins Center. “Her Life.” https://francesperkinscenter.org/learn/her-life/#family.

GovInfo. “Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 243 / December 19, 2024.” https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-12-19/html/2024-30485.htm.

Harvard Magazine. “Frances Perkins: ‘Madam Secretary.’” Harvard Magazine, January-February 2009. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2009/01/frances-perkins.

Library of Congress. New York Tribune, March 26, 1911. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83030214/1911-03-26/ed-1/?r=-0.525,-0.219,2.049,1.676,0.

Miller Center. “Frances Perkins (1933–1945): Secretary of Labor.” University of Virginia Miller Center. https://millercenter.org/president/fdroosevelt/essays/perkins-1933-secretary-of-labor.

National Park Service. “Frances Perkins.” https://www.nps.gov/people/frances-perkins.htm. “Frances Perkins Homestead.” https://www.nps.gov/places/frances-perkins-homestead.htm.

National Women’s Hall of Fame. “Frances Perkins.” https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/frances-perkins/.

Penguin Random House. The Roosevelt I Knew by Frances Perkins. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/308930/the-roosevelt-i-knew-by-frances-perkins/.

Smithsonian Institution Postal Museum. “Women on Stamps, Part 1: Political Firsts.” https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/women-on-stamps-part-1-political-firsts-advising-the-president-and-representing-the.

Smithsonian Institution. “Frances Perkins: The Woman Behind the Weekend, Minimum Wage, and Safer Working Conditions.” Women’s History Blog. https://womenshistory.si.edu/blog/frances-perkins-woman-behind-weekend-minimum-wage-and-safer-working-conditions.

Social Security Administration. “Frances Perkins.” Social Security History. https://www.ssa.gov/history/fperkins.html.

Time. “Frances Perkins: 100 Women of the Year.” TIME, March 5, 2020. https://time.com/5792783/frances-perkins-100-women-of-the-year/.

White House Historical Association. “Frances Perkins.” https://www.whitehousehistory.org/frances-perkins.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Analyzing Photographs & Prints

https://www.whitehousehistory.org/frances-perkins

Caption: Roosevelt’s Cabinet in 1933.

Primary source inquiry:

- What details in the photograph (e.g., clothing, setting, or posture) reflect the cultural or social expectations for women in government during Frances Perkins’s era?

- How do you think Frances Perkins’s education and background influenced her approach to labor reform and social welfare policies?

- What does this photograph reveal about the role and significance of women in leadership positions in the 1930s?

Educator notes:

- Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Photographs & Prints to guide learner inquiry.

Style: Analyzing Newspapers

https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83030214/1911-03-26/ed-1/?r=-0.491,-0.219,1.96,1.676,0

Caption: New York Tribune article covering the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire.

Primary Source Inquiry:

- How did Frances Perkins’s experiences and observations of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire influence her priorities as Secretary of Labor?

- What key labor issues and workers’ rights does Perkins emphasize in her speeches or writings following the fire?

- How does Perkins use language and rhetoric to advocate for improved workplace safety and labor laws?

- How did Frances Perkins confront social and political resistance to labor reforms during her career?

Educator Notes:

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts to guide learner inquiry.

Analyzing Books and Other Printed Texts

Caption: Published memoir of Frances Perkins

Primary Source Inquiry:

- How does Frances Perkins’s memoir reflect the political and social attitudes of her time, particularly regarding labor rights and social welfare?

- What challenges or opposition did Perkins face in pushing for New Deal labor reforms, and how did she navigate those obstacles?

- What strategies did Perkins use to build coalitions and achieve legislative success for workers’ protections?

Educator notes:

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts to guide learner inquiry.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

Related Biographies

Related Biographies

How to Cite this Page

How to Cite this Page

MLA – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Frances Perkins.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Frances Perkins.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/frances-perkins