Revolutionary Spies

Throughout the Revolutionary War, there are stories of heroism; those who sacrificed to save others, those who put their lives on the line to warn of impending danger. The vast majority of these stories involve men. But there are countless extraordinary women who risked and sacrificed just as much as men. While women were not allowed to serve in the military, they found other ways to help the war effort. One way they helped was by spying. British soldiers billeted in the homes of colonialists were sometimes too loose with their secrets. Naturally, women took advantage of this. Many times, these women spies were more successful and better at hiding than their male counterparts. Here are just a few women who accomplished extraordinary things to advance their cause during the revolution.

The Clothesline Code

Anna Smith Strong was a spy based in Setauket, Long Island in New York. She was involved in General George Washington’s spy ring known as the Culper Spy Ring headed by Major Benjamin Tallmadge. Strong and several other residents of Long Island were recruited by Tallmadge who had grown up in Setauket. Other members of the Culper Ring were based in New York City where they spied on the British soldiers. They snuck the information they uncovered to Abraham Woodhull in Setauket who lived next door to Strong. It was her job to signal fellow spy Caleb Brewster that information was ready for him to pick up. She developed an ingenious, almost foolproof signal device to message Brewster: she simply hung her laundry out to dry, in plain sight of British soldiers. Strong hung a black petticoat on her clothesline, along with a number of handkerchiefs. The black petticoat signaled that a message was ready to be picked up and the handkerchiefs would relay where the message was hidden. Six coves along the shore of Long Island were designated as dead drop locations. The number of handkerchiefs hung corresponded to one of the six coves. This messaging system was never broken throughout the entire Revolution and no one in the Culper Ring was ever caught. As a woman, she was severely underestimated, and by doing her laundry, a normal womanly thing to do, no one suspected that she was doing anything out of the ordinary.

The Button Code

Portrait of a woman believed to be Lydia Darragh.

Lydia Barrington Darragh was originally from Dublin, Ireland but moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the 1750s. The Darraghs were Quaker and did not believe in violence, but they sided with the Patriots during the American Revolution. During the occupation of Philadelphia by the British, several high-ranking soldiers were quartered in the Darragh’s home. Additionally, British General Sir William Howe took up camp across the street and would regularly hold meetings with officers in the Darragh’s house. Darragh saw an opportunity to help the Patriots. She regularly spied on the soldier’s meetings, under the guise of bringing them refreshments or wood for the fire. Darragh’s husband, William, wrote the information she uncovered in a special shorthand known to most members of the family. Darragh then hid the message under cloth-covered buttons on her son John’s coat. John then took the message to his older brother, Charles, who was serving in the Continental Army under General Washington.

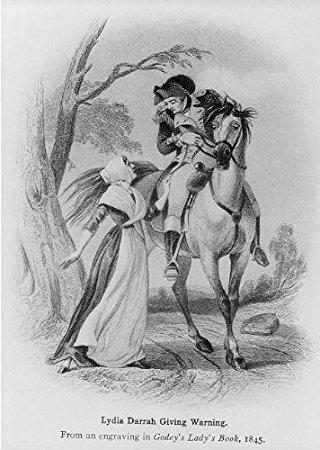

Fictionalized image of Lydia Darragh meeting with a Patriot soldier to pass on secret information.

On December 2, 1777, the British ordered the family to stay in their bedroom while they held a meeting in the house. Darragh hid in a closet to spy on the officers’ meeting where she overheard the soldiers planning a surprise attack on Washington’s army in Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania for December 4, 1777. That night, Darragh left the city with the excuse of getting flour from a mill outside of town. Once there, she met up with Patriot soldiers and handed over a message about the impending attack to Colonel Elias Boudinot. This warning gave Washington’s men time to prepare for the attack which ended in a standoff. Darragh’s bravery and cunning were crucial in ensuring that this attack at Whitemarsh did not end in a massacre.

The British Spies

Women were not just spying for the Patriots during the American Revolution. Many women spied for the British as well. Ann Bates was a teacher in Philadelphia. She was married to a British soldier and was introduced to Major Duncan Drummond early in the war. Drummond decided to use her as a spy. During the summer of 1778, she disguised herself as a peddler named Mrs. Barnes. She then infiltrated Washington’s camp at White Plains, New York on three separate occasions where she sold wares to the men and women camped there. She was instructed to meet a disloyal American soldier named Chambers but was unable to locate him (he had died a few weeks earlier). Instead, she obtained numbers of soldiers, guns, cannon, and other supplies along with locations of munitions stockpiles and officers’ quarters. She successfully brought back all the information to Drummond in Philadelphia who later stated that “her information…was by far superior to every other intelligence.” Because of Bates’ information, General Henry Clinton decided to send more troops into Rhode Island, forcing the Patriot forces to flee.

These three women are just a few of the many women who participated in the American Revolution. Women were largely misjudged and thought to be incapable of strenuous, dangerous work like spying. Many of these women took advantage of this stereotype in order to obtain information that no man would have been able to procure. While many of these women’s names are unknown, it is clear that they helped both sides and may even have influenced the outcome of the war. One such spy, known as Agent 355, remains a mystery but Abraham Woodhull wrote that she “hath been ever serviceable to this correspondence.” Even though women were not allowed to serve in the military, they found other ways to further their cause, often at great personal risk and often for no recognition.

The Culper Ring occasionally used invisible ink in their secret messages. Below is a recipe for invisible ink you can try out at home.

Items:

- lemons

- quill pen or paint brush

- paper

- heat source

Directions:

- Juice the lemon or lemons (fresh juice works best).

- Dip the quill pen in the lemon juice and write out your secret message. Allow to dry.

- Warm up your heat source. A strong lightbulb works best. You can also use a blow dryer or a cast iron skillet and heat it on the stovetop.

- Once your heat source is warm, place the paper in contact with the source. Be sure not to leave it in place for too long as the paper can burn. Continue to warm the paper until the secret message is legible.

Hint: Don’t let your secret message sit around for too long before heating it. After a few days the juice will change color on the paper without a heat source.