Bessie: Three Women Who Did Things Their Own Way

Black History Month was established to recognize and honor African Americans’ contributions to American history and culture. Too often, women are not included on lists of notables and role models. NWHM recognizes women who have made a difference in history.

Bessie Coleman Flew Airplanes Upside Down

Bessie Coleman. 1922.

“Brave Bessie” Coleman became the world’s first female African American licensed pilot. Inspired by the Wright brothers and Harriet Quimby (the first American woman to fly a plane), Coleman believed that she could fly too.

While living in Chicago, Coleman attempted to enroll in flight school but quickly found that no American school would enroll a black woman. She looked abroad instead. Coleman applied to French schools and worked long hours managing a chili parlor by day and studying French at night to prepare. She embarked for France in November1920. In 1921 she became the first female African American pilot in the world when the French Federation Aeronautique Internationale awarded her pilot license number 18310.

Cheering crowds and scores of newspaper reporters greeted Coleman’s return to the US. They were fascinated by her risk taking behavior that was so far removed from their perceptions of how young, black women were to behave. Coleman barnstormed her way across the country, performing daring aerial acrobatics at air shows wherever she could find an audience. She looped de looped and barrel rolled her way into the hearts of cheering—and integrated—crowds. Coleman refused to perform anywhere African Americans were not welcome. And when asked to conform to demeaning stereotypes, she refused saying, “No Uncle Tom stuff for me”.

Coleman dreamed of opening a flight school where other African American women could discover the same excitement and freedom she found in flight. Tragically, Coleman was killed on April 30, 1926 when she fell from an airplane while practicing for an air show. She was 34 years old.

The air is the only place free from prejudice.

Following in Her Wake

Coleman achieved a milestone that continues to elude African American women today. She supported herself as a pilot. While women earn pilots licenses, very few become pilots-for-hire. Almost none are African American.

- 6.6% of licensed pilots are women (2013)

- 4.1% of airline or commercial pilots are women (2014)

- 2.7% of airline transport pilots are African American and a fraction of those are female (2014)

Nice Girls Do So Ride Motorcycles

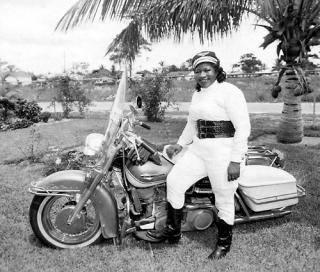

Bessie Stringfield

“The Motorcycle Queen of Miami” Bessie Stringfield loved riding so much that she would drop a penny on a map and ride to wherever it landed. Over sixty years of riding, she proved that “nice girls” did indeed ride motorcycles. And ride them well.

Born in Jamaica in 1911 and adopted by a white Boston couple at age five, Stringfield was naturally drawn to motorcycles, learning to ride at 16. Though her first motorcycle was a 1928 Indian Scout, she was a Harley woman at heart, owning 27 over her lifetime.

By age 19, Stringfield was taking solo cross-country trips, calling them her “penny rides”. Like most African American travelers in the 1930s, Stringfield faced prejudice and intimidation. Motels refused to rent rooms to her. A pickup truck driver once forced her off the road. But she did not give up on adventure.

If you had black skin you couldn’t get a place to stay. I knew the Lord would take care of me and He did. If I found black folks, I’d stay with them. If not, I’d sleep at filling stations on my motorcycle.

Stringfield financed her road trips by performing motorcycle stunts at carnivals where she astounded audiences with her skill and daring. A favorite trick was to ride standing up on the saddle.

During World War II, Stringfield joined the Department of the Army as a civilian motorcycle dispatch rider. She crisscrossed the country eight times delivering messages between military bases. After the war was over, she re-located to Miami, Florida where she continued to perform as a stunt rider and earned the “Motorcycle Queen” moniker. Stringfield rode well into old age, and before dying at age 82 in 1993 reflected to her biographer, "I was somethin'! What I did was fun and I loved it."

The doctor wanted to stop me from riding. I told him if I don't ride, I won't live long. And so I never did quit.

Today’s Women are in the Saddle, Not Just the Calendar

Today, women make up 14% of US motorcycles riders, and it’s especially popular among millennials. Much of the increased popularity is a direct result of US manufacturer Harley Davidson’s focused outreach and marketing to women. After profits dropped in 2009, Harley developed a strategy to appeal to women as riders, rather than passengers. They hosted “garage parties” where groups of women were taught motorcycle basics. Harley even introduced new models designed to fit a woman’s frame. It worked. Thirty three percent of female motorcycle owners have a Harley in their garage. When asked why they ride, their responses would warm Bessie Stringfield’s heart. Riding makes them feel sexy, confident, and happy.

Bessie Smith Sang the Blues

Bessie Smith. February 3, 1936.

Acknowledged as one of the greatest blues singers of the twentieth century, Bessie Smith reigned as the “Empress of the Blues” throughout most of the 1920s.

Smith was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee in the early 1890s. Her earliest performances were on the streets of Chattanooga where she and her brother Andrew busked for spare change. Smith left home in 1912 to join Ma and Pa Rainey’s Rabbit Foot Minstrels troop and traveled throughout the South on the minstrel and vaudeville circuit. Smith developed an expressive and distinctive style whose emotional intensity connected with audiences. Bessie didn’t just sing the blues; she told stories of love, loss, and heartache.

Smith toured the black vaudeville circuit for ten years before making it big on the national scene. The Theater Owners’ Booking Association (TOBA) booked African American performers in mostly southern venues for black audiences. Entertainment was strictly segregated. Black performers occasionally appeared before white audiences but never in reverse. Tours were grueling. Companies traveled relentlessly, playing short gigs in run down venues.

Smith’s rise to stardom corresponded to an awakening interest in black music by white patrons. Prohibition went into effect in 1920 just as American society liberated itself from straitlaced, Victorian notions of propriety. Music like jazz and the blues with their earthy and sexual themes became a popular accompaniment to speakeasy culture and the liberated flapper.

Smith was overlooked in the first wave of African American performers who crossed over into white venues, in clubs and on records. Her “look” did not conform to the period’s popular standard of prettiness. She was full figured and dark skinned. Her interpretation of the blues was deeply rooted in the African American culture that created it, imbuing it with an unmistakable authenticity. A little too authentic for early cross-over audiences. Smith’s charisma and talent propelled her onto the national stage.

Smith’s first record, “Down Hearted Blues” (1923), was a smash hit, selling 780,000 copies in the first six months. By the end of the 1920s, Smith was the most successful black performer, male or female, in the US. At the height of her career, she earned up to $2000 per week or the equivalent of about $26,000 in 2016 dollars performing in both black and white clubs, predominantly in the South and Midwest. She made 160 records over a ten-year recording career fueling her popularity.

No time to marry, no time to settle down: I'm a young woman, and I ain't done runnin' around.

The Great Depression and changing musical tastes stalled Smith’s career in the 1930s. After losing her recording contract in 1933, she transitioned to jazz and big band music and continued to tour. She performed with both black and white musicians including Louis Armstrong, Lonnie Johnson, and Benny Goodman. Smith was slowly climbing her way back up to the top when she died in 1937 as the result of a car accident in Mississippi. Though she was no longer a super star, her funeral drew 5000 loyal friends and fans.

In the words of biographer Chris Albertson, “Bessie had a wonderful way of turning adversity into triumph, and many of her songs are the tales of liberated women.”

Further Reading on Bessie Coleman

Gubert, Betty Kaplan, Miriam Sawyer, and Caroline M. Fannin. Distinguished African Americans in aviation and space science. Westport, Conn: Oryx Press, 2001.

Further Reading on Bessie Stringfield

Ferrar, Ann. Hear me roar: women, motorcycles, and the rapture of the road. North Conway, N.H.: Whitehorse Press, 2000.

Further Reading on Bessie Smith

Albertson, Chris. Bessie. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2005.