Aunt Jemima® and Betty Crocker

Aunt Jemima® and Betty Crocker have been American cultural icons for decades, but neither of these women ever existed. Both were created by marketers to better sell products. What is especially incredible about these two marketing campaigns is the years consumers believed they were depicting real women. Aunt Jemima was created in the 1890s and Betty Crocker was developed about thirty years later in the 1920s. While there have been updates to both characters since their creation, until recent years both remained stuck in the time period they were created and helped to perpetuate stereotypes.

It was and still is common to use women in marketing campaigns around food products. Since women have long been seen by marketers as the primary consumer of domestic products there has been a focus on selling to women by women. Betty Crocker’s campaign was so well done, according to an April 1945 Fortune magazine, she was the second best known American woman, only after Eleanor Roosevelt. While never quit as well-known as Betty Crocker, Aunt Jemima has also had a lasting impact on consumers and sparked decades of racial debates.

Looking Backwards to Sell

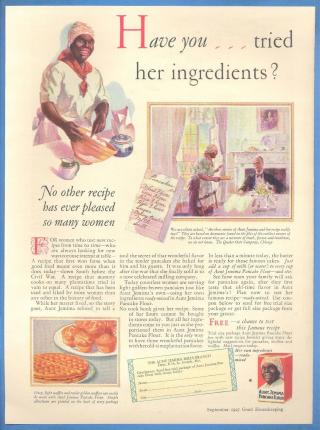

Originally Aunt Jemima was a ready mix created in 1889 by the Pearl Milling Company. This product sparked a brand, which included the character of Aunt Jemima. Nancy Green, a cook and storyteller, was the first woman hired to bring Aunt Jemima to life. She played the character at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Aunt Jemima was depicted as a formerly enslaved cook who spoke with a stereotypical enslaved dialect. Her clothing reflected the same idea, dressed in the costume of a post-Civil War formerly enslaved woman, wearing a simple dress, apron, and head scarf.

1927 Aunt Jemima Ad

At the 1933 World’s Fair Aunt Jemima was portrayed by another woman, Anna Robinson. Robinson not only appeared at the fair, but also traveled the country promoting the Aunt Jemima line of products. It became a social event to go and see Aunt Jemima make pancakes. This lead to changes in the Aunt Jemima logo so it was a closer likeness to Robinson.

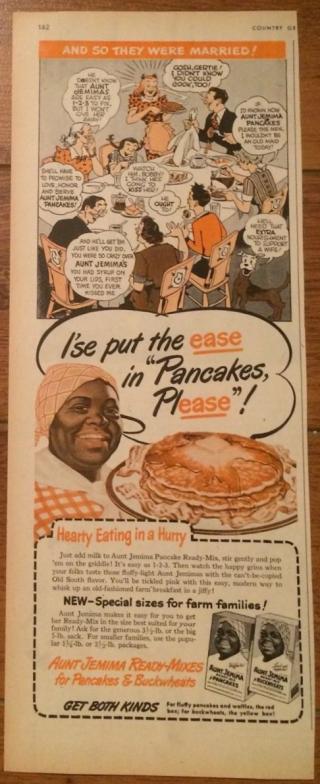

While the character was not created until the 1890s, Aunt Jemima’s clothing and language in 1950s still harked back to the post-Civil War time period. In this ad, Aunt Jemima is quoted saying “I’se” instead of “I”, highlighting the racist dialect the character used. Her clothing was also not updated and still represents post-Civil War African Americans. In these ads often the only African American included is Aunt Jemima and they perpetuate a glorified view of life on a plantation in the South.

1950s Aunt Jemima Ad

Betty Crocker was Born

Betty Crocker’s creation was a bit different from Aunt Jemima’s. Instead of being created as part of a logo, Betty Crocker was developed a piece at a time. Throughout the late 1910s and early 1920s, the Washburn Crosby Company (a precursor to General Mills), received thousands of questions from women across the country about their baking conundrums. In 1921, the Washburn Crosby’s advertising department decided the best solution was to create a warm, friendly, and authoritative figure who could answer these questions.

Betty Crocker’s last name was taken from a recently retired director of Washburn Crosby, William G. Crocker. “Betty” was chosen as the character’s first name for its wholesome and maternal quality. To create her signature a contest was held among the female employees at Washburn Crosby and the most unique was selected. It is the same signature still used today. From that point on, Betty Crocker signed response to letters written to the company on baking, cooking, and domestic issues. In 1924, her voice was created when Washburn Crosby began airing a cooking radio show called, the Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air. Marjorie Child Husted provided the first Betty Crocker voice. When the show was picked up by multiple stations, additional women voiced Betty Crocker. Husted, a home economist, continued to voice her show and wrote the scripts for all of the other Betty Crockers.

1940s Betty Crocker Ad

In 1936, Betty Crocker was given a face. Artist Neysa McMein blended the facial features of the Washburn Crosby Home Service Department’s female employees. While created base on a representation of working women, Betty Crocker was not dressed as a professional woman. Since then, Betty Crocker’s look has updated multiple times to better reflect the women buying her product.

Modern Women

Aunt Jemima and Betty Crocker are still prominent characters today, helping to sell many products. Since their creation each woman’s appearance has been altered to relate to a wider audience. Aunt Jemima’s skin lighted over time, whereas Betty Crocker’s skin was darkened to olive in 1996 to give her a more multicultural look. Both women also wear more professional clothing. Today Aunt Jemima wears a lace collar and pearl earrings. Betty Crocker, who does not appear on her products, no longer wears a suit jacket, instead she wears a simple red sweater. These updated looks help modern consumers relate to the characters, not real women, on their favorite flour mixes.

2017 Aunt Jemima Logo

Marks, Susan. Finding Betty Crocker: The Secret Life of America's First Lady of Food. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

Avey, Tori. "Who Was Betty Crocker?" PBS. February 15, 2013. Accessed May 10, 2017.

"Our History." Aunt Jemima. Accessed May 10, 2017.

"The Story of Betty Crocker." Betty Crocker. Accessed May 10, 2017.

"Who Was Betty Crocker?" Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Accessed May 10, 2017.