African American Reformers

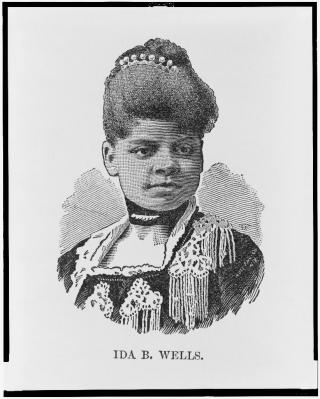

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

In the 1890s, the growth of the black women’s club movement was spurred on by efforts to end lynching. Ida B. Wells-Barnett denounced lynching in the press. As she traveled the country lecturing about lynching, she also helped to found black women’s clubs. Many of these clubs addressed problems similar to those addressed by white women’s clubs, including health, sanitation, education, and woman suffrage. However, black women’s clubs also focused on combating racism and on racial uplift.

In 1896, black women’s clubs joined together to form the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACW) under the leadership of Mary Church Terrell. The motto of the NACW was “Lifting as We Climb.” One of the most effective black women’s clubs was the Neighborhood Union in Atlanta, run by Lugenia Burns Hope. The Neighborhood Union divided the city into districts and zones, thus effectively reaching almost every black American in Atlanta.

Mary Church Terrell

Black women also founded mutual benefit societies, settlement houses, and schools. Some black female workers, particularly laundresses in the South, made efforts to unionize and undertook strikes. Black women in the North also worked to provide services for black women recently arrived from the South. The National League for the Protection of Colored Women, which later merged with other organizations to form the National Urban League, and “colored chapters” of the YWCA offered services to female migrants. Black women were involved in the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and performed much of the local work.

Notable black women reformers include Mary McLeod Bethune, who founded the National Council of Negro Women, the Southeastern Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and the Bethune-Cookman Institute; Nannie Helen Burroughs, who founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC; and Maggie Lena Walker, the first American woman bank president, who was also head of one of the largest and most successful black mutual benefit societies.

Sources

- Cooney, Jr. Robert P.J. Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement. American Graphic Press, 2005.

- Frankel, Noralee and Nancy S. Dye, editors. Gender, Class, Race, and Reform in the Progressive Era. The University of Press of Kentucky, 1991.

- Ginzberg, Lori D. Women and the Work of Benevolence: Morality, Politics, and Class in the Nineteenth-Century United States. Yale University Press, 1990.

- Muncy, Robyn. Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890-1935. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Muncy, Robyn. "Julia Clifford Lathrop." Women Building Chicago 1790-1990: A Biographical Dictionary. Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast, editors. Indiana University Press, 2001. 490-2.

- Orleck, Annalise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965. University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Open Collections Program: Working Women, 1800-1930. Harvard University Library. http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/ww/

- Rosenberg, Rosalind. Beyond Separate Spheres: Intellectual Roots of Modern Feminism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

- Scott, Anne Firor. “Most Invisible of All: Black Women’s Voluntary Associations.” The Journal of Southern History. Vol. LVI, No. 1, February 1990.

- Schneider, Dorothy and Carl J. Schneider. American Women in the Progressive Era, 1900-1920. Facts on File, Inc., 1993.

- Sklar, Kathryn Kish. Florence Kelley and the Nation's Work: The Rise of Women’s Political Culture, 1830-1900. Yale University Press, 1995.