Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina

Palais Garnier (Dec 29, 2012)

Palais Garnier (Dec 29, 2012)by Naoya Ikeda

National Women’s History Museum

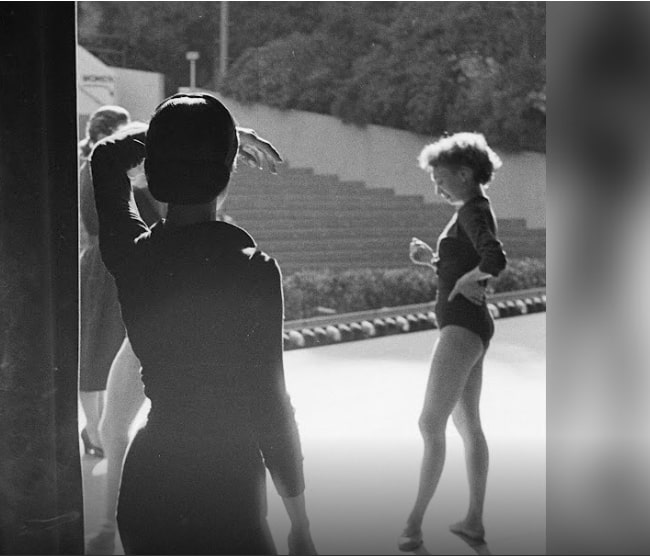

In 1947, a 22-year-old Maria Tallchief traveled to Paris to perform at the Opera House. Post WWII, the Opera House needed a reset after its wartime director, Serge Lifar, collaborated with the Nazis. Maria’s performance was part of that reset. Parisians were excited to see the “daughter of an Indian Chief” dance.

Performing choreography she learned last minute, in new shoes and on a poorly constructed stage, Maria wowed the audience with her mix of artistry and athleticism. But people were interested in her for more than her skill. She not only represented the United States, but her Native American identity and culture. And she did that proudly.

(1961)

(1961)by Alfred Eisenstaedt

LIFE Photo Collection

Early Life

"When I was three, Mother took me for my first ballet lesson...What I remember most is that the ballet teacher told me to stand straight and turn each of my feet out to the side, the first position." —Maria

Maria Tallchief, age 3 or 4 (1929)

Maria Tallchief, age 3 or 4 (1929)by Granger

National Women’s History Museum

Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief was born in a small hospital on January 14, 1925 in Fairfax, Oklahoma to Ruth Porter and Alexander Joseph Tall Chief, member of the Osage Nation. Her younger sister, Marjorie, was born a year later.

Brought up on the reservation and taught to be proud of her Native American heritage and identity, Maria grew up listening to stories, particularly from her “Indian Grandma Tall Chief.” Her grandmother, wearing a tribal blanket over her shoulders and a single braid down her back, would tell Maria and her sister stories of the Osage.

Tall Chief Theatre, Fairfax (OK)

Tall Chief Theatre, Fairfax (OK)by Oklahoma Historical Society

National Women’s History Museum

Grandma Tall Chief told the girls about how white settlers and the U.S. government had forced the Osage to move time and time again because they wanted Osage land. In the early 1870s, the U.S. government forced the Osage to move again to presumably worthless, rocky, inarable land in northwest Oklahoma. That land included Maria’s hometown, Fairfax.

The land actually contained one of the richest oil deposits then in the United States.

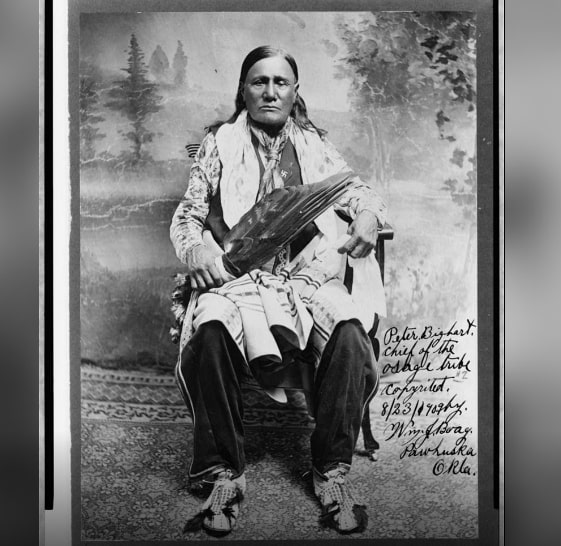

Peter Bighart [sic], chief of the Osage tribe (1906)

Peter Bighart [sic], chief of the Osage tribe (1906)National Women’s History Museum

Grandma Tall Chief spoke proudly about her father, Chief Peter Bigheart, who played an important role in negotiating the 1906 federal treaty giving the Osage “headrights” to all proceeds from the oil. Headrights were inherited, and Maria’s father held one.

These headrights made the Osage wealthy. The only way an Osage could lose his or her headright was through death.

In 1923, the height of the oil boom, the Osage received the equivalent of $400 million. Maria’s family benefitted and she remembered, “as a young girl growing up on the Osage reservation...I felt my father owned the town.”

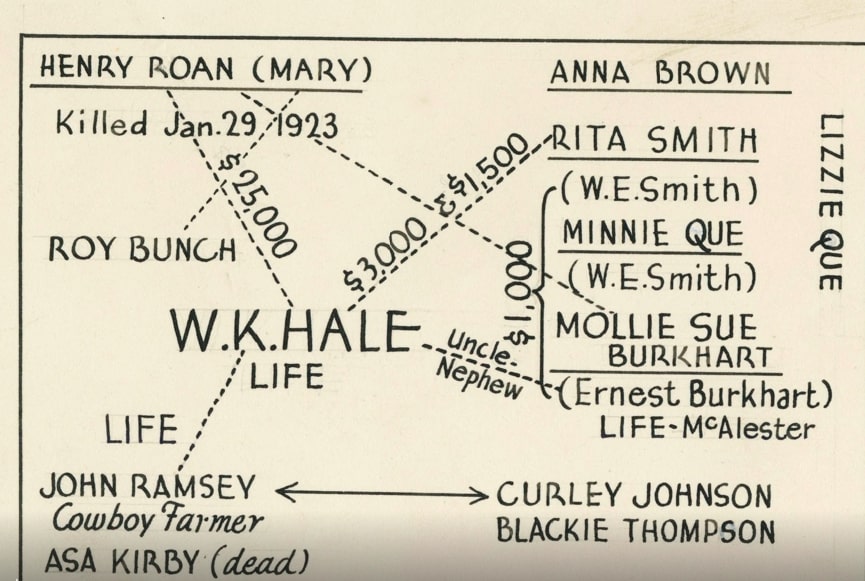

Hale-Ramsey murder case

Hale-Ramsey murder caseby Oklahoma Historical Society

National Women’s History Museum

While Maria was not alive when it happened, she knew the stories. Osage were murdered by people who wanted their headrights for themselves. These murders were rarely investigated. Maria’s cousin Pearl became an orphan when her family home was firebombed by those looking to claim Pearl's headright.

The "Reign of Terror" ended in 1925 with the conviction of a wealthy rancher and two accomplices. In 1925 the Federal Government outlawed the passage of headrights from tribal members to non-Osage in an attempt to prevent this violence from happening again. By 1965, Oklahoma had paroled the three men and one received a pardon.

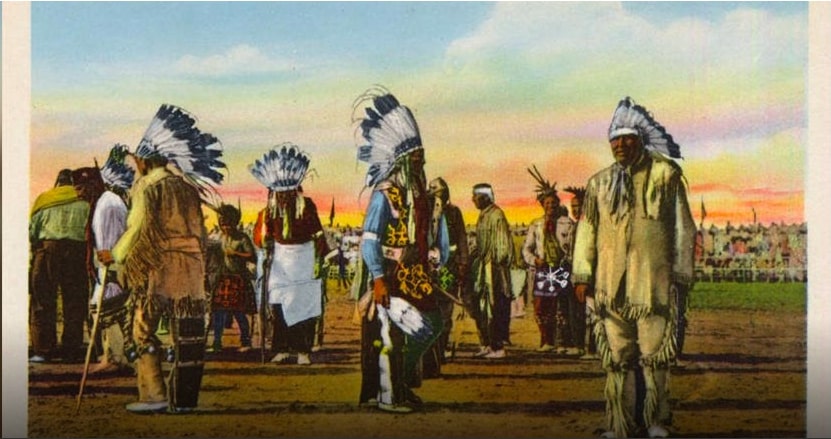

Postcard view of a group of Osage Indian dancers (1940)

Postcard view of a group of Osage Indian dancers (1940)by Unknown Author, Curt Teich Postcard

National Women’s History Museum

Knowing her people were under threat did not stop Maria from pursuing her passions. Maria loved to dance and she started ballet lessons young. She also loved watching Osage men dance at pow wows. Maria always had the rhythm of pow wow songs in her head.

At their mother's urging, the sisters would perform for mostly white audiences at rodeos and state fairs. They made her feel self-conscious. She remembers wearing "toe shoes...under my moccasins...fringed buckskin outfits, headbands with feathers, and bells on [my] legs," a costume she felt was a stereotype. She “was relieved when we put those bells away for good.”

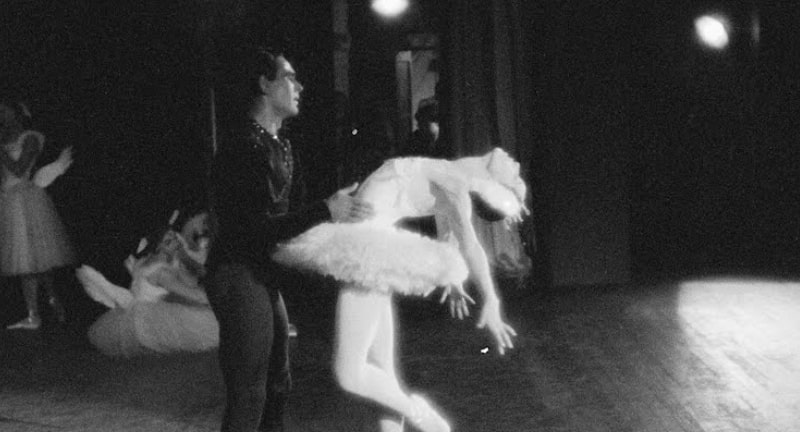

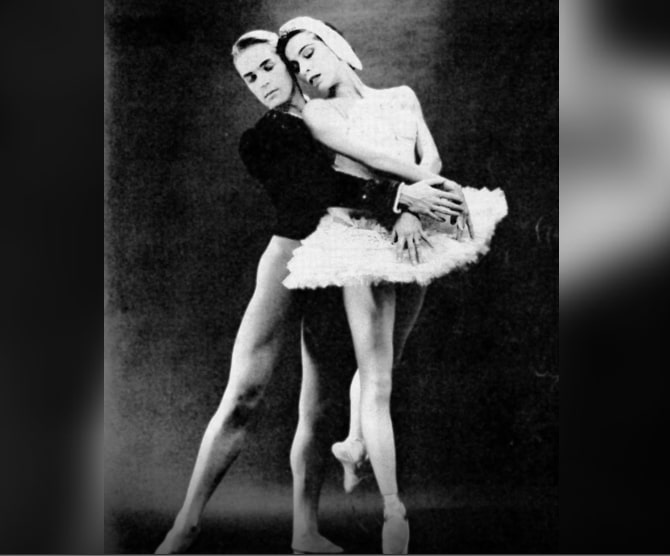

Maria Tall Chief "Swan Lake" (Jul 1953)

Maria Tall Chief "Swan Lake" (Jul 1953)by Edward Clark

LIFE Photo Collection

To encourage the girls’ dance talents, the family moved to Los Angeles when Maria was 8. At age 12, she began training with Bronislava Nijinska, a noted Russian ballerina and choreographer. Maria remembers even though Nijnska spoke no English, she trained her beautifully.

In L.A. her highschool classmates made fun of her last name and "war whooped" when they saw her. They asked why she did not wear feather headdresses or if her father took scalps. It pained her that her classmates saw her as a stereotype and that they could not understand why she was proud to be Osage. She started spelling her last name as “Tallchief.”

Maria Tall Chief "Swan Lake" (Jul 1953)

Maria Tall Chief "Swan Lake" (Jul 1953)by Edward Clark

LIFE Photo Collection

Beginning of Career

"You have to show that you want to dance with all your heart...even in the corps. You shouldn't just expect a role to be handed to you."—Ruth, Maria's mother

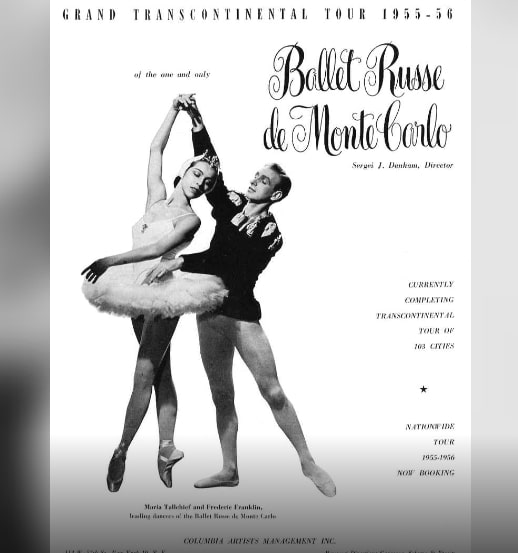

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo promotion (Jan 1,1955)

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo promotion (Jan 1,1955)by Columbia Artists Management Inc.

National Women's History Museum

After graduation, Maria moved to NYC to start her dream career with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, a company Maria loved and had seen numerous times in L.A. While with the company, she met George Balanchine, the famous choreographer.

As her star began to rise, Maria was pressured to adopt a Russianized name so she could blend in with the ballet world. She refused. At the suggestion of choreographer Agnes de Mille, who felt her first name was too common, she used her middle name, going by “Maria Tallchief” on stage. With this proud Osage name, she took her first step to becoming the first American and Native American prima ballerina.

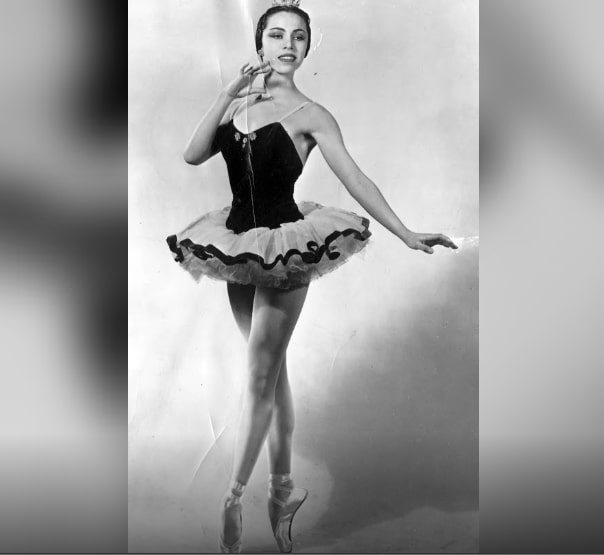

Maria Tallchief (Jan 1, 1954)

Maria Tallchief (Jan 1, 1954)by Unknown Photographer

National Women's History Museum

At the beginning of Maria’s career, the United States did not have a substantial ballet culture. All the great ballet performers, choreographers, and companies were Russian or European. But the U.S was making inroads in the international ballet world. One famous example of American ballet was the one choreographed by Agnes de Mille set to Aaron Copland's “Rodeo." Maria performed a featured role in that dance.

Maria Tallchief and George Balanchine (1956)

Maria Tallchief and George Balanchine (1956)by Philippe Halsman

National Women's History Museum

The relationship she began with George Balanchine at the Ballet Russe developed and they discussed marriage. Her family was not supportive. Always true to herself, Maria married Balanchine on August 16, 1946. During their marriage, he choreographed dances for Maria. When Balanchine started the New York City Ballet (NYCB) in 1948, he made Maria the company’s prima ballerina.

While the marriage was short, the partnership continued. After their separation in 1950, Balanchine continued choreographing for his “Darling Maria." The final part Balanchine choreographed for her was the lead in 1957’s Gounod Symphony.

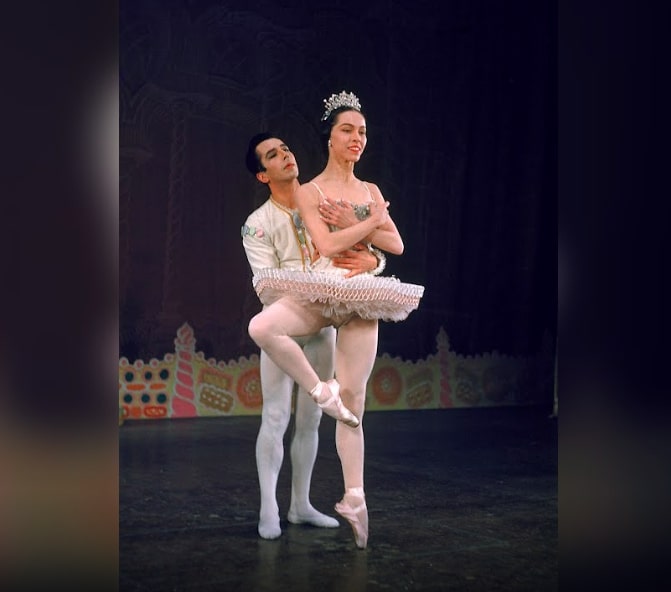

Tallchief and Magallanes in The Nutcracker

Tallchief and Magallanes in The Nutcrackerby Dance Magazine

National Women's History Museum

Maria starred in many NYCB productions from its founding until 1965. Her standout performances included the role of the magic bird in Firebird (1949) and the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker (1954). Balanchine’s new choreography offered bold reimaginings of these older productions and both soon became classics in the genre. The Nutcracker became an annual holiday season tradition for ballet companies throughout the country.

In its review of Firebird, The New York Times praised Maria for disappearing into the role: “she never departs from the style of the role and its character; she is always the magic bird, and the captive bird... Miss Tallchief has been a fine dancer for some time, but here she has really outdone herself. It is no wonder the audience shouted itself hoarse.”

Maria’s starring roles in these popular ballets, along with many other prominent performances, helped cement her in the public’s mind as the first American prima ballerina.

(1961)

(1961)by Alfred Eisentaedt

LIFE Photo Collection

“Onstage Maria looks as regal and exotic as a Russian princess; offstage, she is as American as wampum and apple pie.” - Time magazine, 1951.

Many Americans took pride in Maria as the nation’s prima ballerina, as well as in the growing international reputation of American ballet. Press coverage of Maria often emphasized her “American,” down-to-earth nature, in an attempt to contrast her with “diva-like” Russian and European ballerinas. This expression of national pride also stemmed from the country’s new leadership on the world stage following Allied victory in World War II. Many Americans no longer felt as deferential to Old World art and culture as they had in in the past.

The media’s attention to Maria’s Osage heritage both conflated Native identity with Americanness, and clearly marked Native Americans as foreign “others.” But Maria’s continued success, and her constant pride in her Osage heritage, ensured that both aspects of her identity were visibly intertwined. Maria was weary of being known solely as an Indian ballerina, but neither did she want to ignore her heritage. In her autobiography she wrote, “Above all, I wanted to be appreciated as a prima ballerina who happened to be Native American.”

(Jul 1953)

(Jul 1953)by Edward Clark

LIFE Photo Collection

Maria’s national and international profile skyrocketed in the 1950s and early 1960s. She graced the covers of magazines such as Newsweek (1954), Holiday (1952), and Dance Magazine (1954). Newsweek called her, “the finest American-born ballerina the 20th century has produced.” In what she called “a major breakthrough for American ballet,” Maria and the NYCB performed on NBC’s televised concert series, “The Bell Telephone Hour” in 1959. Maria toured Europe and Asia with the NYCB and danced with other companies like American Ballet Theatre and The Royal Danish Ballet. Her 1960 tour of the Soviet Union solidified her international stardom.

Maria was even featured in the Hollywood film Million Dollar Mermaid (1952). She portrayed the famed early-twentieth century Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova. The Oklahoma-born Maria found it quite amusing to attempt a Russian accent, but she focused on the dancing: a hybrid of Pavlova’s famous The Dying Swan and her own Firebird.

Maria Tallchief Receives Dance Magazine Award (Apr 28, 1961)

Maria Tallchief Receives Dance Magazine Award (Apr 28, 1961)by Dance Magazine

National Women's History Museum

Maria’s many awards reflected her success at the highest levels of the ballet world as well as her Osage, Oklahoman roots. She received honors like Mademoiselle's “Woman of the Year” in 1951 and Dance Magazine's Annual Award in 1960. Maria also won the 1965 Capezio Award, one of the most prestigious prizes in dance.

But she also received accolades closer to home. The Oklahoma State Senate declared June 29, 1953, “Maria Tallchief Day,” and the Osage Nation hosted a celebration where they named Maria Princess Wa-Xthe-Thonba (Princess Two Standards). Maria’s grandmother selected the name: “By choosing it she was saying that while I was a ballerina with an important career on the stage, I was also her grandchild, an Osage woman and daughter of the tribe.” In 1967, Maria received the Indian Council of Fire Achievement Award and in 1972 she was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame.

Late Career & Legacy

"As an American ballerina, she has brought luster to American ballet itself, contributing immeasurably in placing it on equal esthetic footing with the ballet standards of those European cultures which first nurtured the art of ballet."- Capezio Award inscription, 1965

Tallchief and Bruhn (1961)

Tallchief and Bruhn (1961)by Dance Magazine

National Women's History Museum

Maria continued as the prima ballerina for the NYCB until 1965, though she briefly left the company in 1954. The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo lured her away from NYCB with the offer of a $2,000 per week salary, making her the highest paid ballerina in the world at the time. But, disappointed with her experience at Ballet Russe, Maria left after one year and returned to NYCB.

Tired of life on the road and ready to settle with her family in Chicago, Maria left the NYCB in 1965. Her final performance was dancing Romeo and Juliet on “The Bell Telephone Hour” in 1966 at age 41.

Maria Tallchief (1961)

Maria Tallchief (1961)by Dance Magazine

National Women's History Museum

After Tallchief and Balanchine’s marriage ended, Maria married aviator Elmourza Natirboff in 1952. But Natirboff could not accept the amount of time and effort that Maria’s demanding career required, and they divorced in 1954. Two years later, Maria married Chicago businessman Henry “Buzz” Paschen. In 1959 they welcomed a daughter, Elise Maria Paschen. Maria permanently settled with Paschen in Chicago in 1966 and the two were married until his death in 2004.

Maria Tallchief en pointe (1961)

Maria Tallchief en pointe (1961)by Chicago Tribune

National Women's History Museum

Maria continued to make her mark on the dance world as a teacher and director in Chicago. In 1974, she formed the Ballet School of the Chicago Lyric Opera. After the program lost its funding, Maria, along with her sister and husband, established the Chicago City Ballet (CCB) in 1980. The state of Illinois provided $100,000 in funding to the school, demonstrating the growing importance of ballet as an art form in the United States. Tallchief served as the Artistic Director of the CCB until 1987.

Tallchief’s work with the Lyric Opera and the CCB left a legacy in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune wrote that Tallchief was a major contributor to the city’s dance revival that began in the late-twentieth century. Tallchief also endeavored to preserve Balanchine’s legacy as a historian extraordinaire for The George Balanchine Foundation, teaching young dancers Balanchine’s intentions for her parts in several of his ballets.

Flight of Spirit Painting

Flight of Spirit Paintingby OakleyOriginals

National Women's History Museum

Maria continued to earn honors for the pride she brought to the United States and to Native Americans. In 1999, President Bill Clinton presented Tallchief with the National Medal of the Arts. He stated, “Maria Tallchief took what had been a European art form, and made it America's own. How fitting that a Native American woman would do that. With magic, mystery and style, she soared above all.”

In 1991, she and four other Native ballerinas from Oklahoma (Yvonne Chouteau, Rosella Hightower, Moscelyne Larkin, and her sister, Marjorie, collectively known as “The Five Moons”) were honored with a mural in the state capitol entitled Flight of Spirit.

Misty Copeland as Firebird, American Ballet The... (May 19, 2016)

Misty Copeland as Firebird, American Ballet The... (May 19, 2016)by notmydayjobphotography

Maria sought to empower younger generations, speaking to American Indian groups about Native Americans in the arts and educating students about Native histories. She helped raise funds for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, and, in 2018, she was posthumously selected as one of the first 12 inductees to the National Native American Hall of Fame.

Maria passed away in Chicago in 2013 at the age of 88. Her legacy lives on in the success of American ballet and in the growing numbers of dancers of color in the U.S. In 2015, Misty Copeland made history as the American Ballet Theatre’s first African-American female principal dancer. Copeland stepped into Tallchief’s shoes when she starred in Firebird (2012, 2016). Copeland co-wrote a 2014 children’s book, aimed at encouraging young dancers of color to pursue their dreams. Its title, fittingly, is Firebird.

Maria and the rest of “The Five Moons” helped foster a vibrant Native American ballet culture. Today, Indian dance groups across the country blend classical ballet styles with Native dance traditions to create original, innovative productions. The Osage Ballet Company’s Wahzhazhe (2012) tells the history of the Osage people over 200 years, uniting traditional Osage culture with the ballet excellence embodied by Maria Tallchief.

Credits

National Women's History Museum.

National Women's History Museum.

Exhibit curated and written by Emma Rothberg, 2020-2022 NWHM Predoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies, and Mariana Brandman, 2020-2022 NWHM Predoctoral Fellow in Women's History.

Works Cited:

Aloff, Mindy. "Tallchief, Maria (24 January 1925–11 April 2013)." American National Biography. 1 Oct. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1803916

Anderson, Jack. “Maria Tallchief, Dazzling Ballerina and Muse for Balanchine, Dies at 88.” New York Times. April 12, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/13/arts/dance/maria-tallchief-brilliant-ballerina-dies-at-88.html.

Anderson, Jon and Sid Smith. “Maria Tallchief Dead at 88.” Chicago Tribune. April 12, 2013. https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/ct-xpm-2013-04-12-ct-ent-0413-tallchief-obit-20130413-story.html.

Chua-Eoan, Howard. “The Silent Song of Maria Tallchief: America’s Prima Ballerina (1925-2013).” TIME. April 12, 2013. https://entertainment.time.com/2013/04/12/the-silent-song-of-maria-tallchief-americas-prima-ballerina-1925-2013/.

Grann, David. “The Forgotten Murders of the Osage People for the Oil Beneath their Land.” PBS News Hour. February 15, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/the-forgotten-murders-of-the-osage-people-for-the-oil-beneath-their-land.

Homans, Jennifer. “When Maria Tallchief Took Paris by Storm.” New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/news/the-lives-they-lived/2013/12/21/maria-tallchief/.

Kowal, Rebekah J. “‘Indian Ballerinas Toe Up’: Maria Tallchief and Making Ballet ‘American’ in the Tribal Termination Era.” Dance Research Journal 46, no. 2 (2014): 73-96.

Krol, Debra. “National Native American Hall of Fame names first twelve historic inductees.” Indian Country Today. October 22, 2018. https://indiancountrytoday.com/news/national-native-american-hall-of-fame-names-first-twelve-historic-inductees-e-Uu9NZBh0K9TPrv992tyQ

Livingston, Lili Cockerille. American Indian Ballerinas. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

"Maria Tallchief." National Women's Hall of Fame. https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/maria-tallchief/.

May, Jon D. “Osage Murders.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=OS005.

Rynder, Constance. "Maria Tallchief" in Markowitz, Harvey, and Carole A. Barrett. American Indian Biographies. Vol. Rev. ed. Magill’s Choice. Pasadena, Calif: Salem Press, 2005.

Tallchief, Maria and Larry Kaplan. Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

Thomas, Heather. "Maria Tallchief: Osage Prima Ballerina." Library of Congress. November 19, 2019. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2019/11/maria-tallchief-osage-prima-ballerina/.

Toll, Shannon. "Maria Tallchief, (Native) America's Prima Ballerina: Autobiographies of a Postindian Princess." Studies in American Indian Literatures 30, no. 1 (2018): 50-70. muse.jhu.edu/article/692228.

“Wahzhazhe: An Osage Ballet.” Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. https://www.si.edu/object/yt_ipwe0Jluhpo

YouTube Videos:

Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian."Wahzhazhe: An Osage Ballet." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ipwe0Jluhpo