Making a Difference: The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps

At this moment of my induction into the United States Cadet Nurse Corps of the United States Public Health Service, I am solemnly aware of the obligations I assume toward my country and toward my chosen profession; I will follow faithfully the teachings of my instructors and the guidance of the physicians with whom I work; I will hold in trust the finest traditions of nursing and the spirit of the Corps; I will keep my body strong, my mind alert, and my heart steadfast; I will be kind, tolerant, and understanding; Above all, I will dedicate myself now and forever to the triumph of life over death; As a Cadet nurse, I pledge to my country my service in essential nursing for the duration of the war.

- The Cadet Nurses Pledge

In the first year of the United States’ involvement in World War II, military nursing services pulled nearly thirty percent of active graduate nurses from hospitals, health agencies, schools and institutions, causing a drastic shortage of nurses. Although $5 million was appropriated by Congress in 1942 through passage of the Labor-Security Agency Appropriation Act in an attempt to assist nursing schools address the shortage of trained nurses, the sum was not sufficient to train nurses fast enough to meet the rapidly rising demand. With the need for nurses continuing to rise, and with no centralized recruiting effort in place, other higher paying jobs for women in the defense industry and factories began to further drain the pool of prospective nursing candidates.

In an effort to solve this problem, Congresswoman Frances P. Bolton, a Republican from Ohio and a longtime champion of nursing education, introduced a bill in March of 1943. The bill called for the establishment of a government program to provide grants to schools of nursing to facilitate the training of nurses to serve in the armed forces, government and civilian hospitals, health agencies, and in war related industries. The Bolton Act passed both houses of Congress and became law on July 1, 1943, with an initial appropriation of $65 million for the first year. The responsibility for the Cadet Nurse Corps was placed under the Public Health Service (PHS), and was answerable to Thomas Parran, the US Surgeon General. The Division of Nurse Education was established in 1943 and Surgeon General Parran appointed Lucille Petry, RN, as the head of the Cadet Nurse Corps, making her the first woman to head a major division of PHS.

Any young woman interested in becoming a nurse was eligible for the Cadet Nurse Corps. An amendment to the original Bolton Act stated that the Nurse Cadet Corps would not discriminate based on race. As a result of this amendment, forty Native Americans representing twenty-five tribes were able to enroll through the program, as well as 3,000 African Americans. Most notable, especially for the time, was the participation of relocated Japanese Americans. The only requirements a potential student had to meet were that she be between the ages of 17 and 35, be in good health, and have graduated from an accredited high school with good grades. Once they were accepted into an accredited nursing school, qualified applicants received scholarships that covered their tuition and fees, as well as a small monthly stipend. In return, Cadets were expected to complete their training in 30 months and to provide essential nursing services for the duration of the war, either in the military or civilian life.

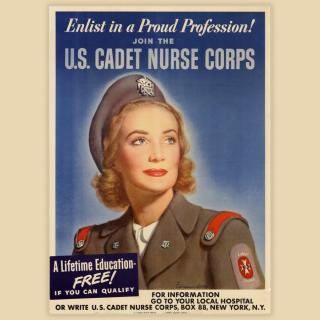

With the Corps active, a vigorous campaign was launched in order to recruit the required number of nursing students to the program, as well as to convince parents that a career in nursing was worthwhile for their daughters. The Office of War Information distributed millions of leaflets to towns and cities across the country. Advertisements and articles ran in magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Harper's Bazaar, Vogue and the Ladies' Home Journal. Cadet Nurses attended war bond rallies, patriotic parades, and were featured in movie newsreels and features, radio soap operas, variety shows and numerous color posters that were prominently placed in areas frequented by high school girls.

The Cadet uniform was another important element of the recruitment campaign, with leading fashion designers of the day brought in to show their interpretation of the uniform to fashion editors, who then chose both summer and winter attire for the Cadets. New recruits were issued a summer uniform of a two-piece gray and white striped cotton suit, and a winter uniform of a gray wool suit with a single-breasted jacket. They were also issued a winter overcoat of gray velour, a gray twill raincoat and a gray Montgomery beret.

In the end, the recruitment effort was an unmitigated success, and the Cadet Nurse Corps was able to meet its yearly quota of 65,000 nurses for the first three years of its existence. Between 1943 and 1948, when the last class of sponsored recruits graduated, just over 124,000 women had enrolled in the Cadet Nurse Corps. In addition to recruiting and training young women, the Cadet Nurse Corps helped to transform nursing education in the United States. The funding that was provided through the Corps allowed nursing schools to build modern facilities, upgrade laboratory equipment, and helped to integrate nursing programs that had previously accepted only white students. More broadly, the Cadet Nurse Corps program ensured that Americans, whether they were serving in the military or holding down the home front, had access to the nursing care that they needed.

Heather Willever, and John Parascandola. "The Cadet Nurse Corps, 1943-48." Public Health Reports (1974-) 109, no. 3 (1994): 455-57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4597613.

"LibGuides: Short History of Military Nursing: U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps." U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps - Short History of Military Nursing - LibGuides at University of Wisconsin-Madison Ebling Library. Accessed April 12, 2019. https://researchguides.ebling.library.wisc.edu/c.php?g=293228&p=1953290.

Petry, L. "The Public Health Significance of the U. S. Cadet Nurse Corps." American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. November 1943. Accessed April 12, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1527450/.

MLA - Eberlein, Liz. "Making a Difference: The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2019. Date accessed.

Chicago - Eberlein, Liz. "Making a Difference: The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps." National Women's History Museum. 2019. www.womenshistory.org/articles/making-difference-us-cadet-nurse-corps.