Esther Lederberg

Summary

-

Esther Lederberg co-developed key techniques in bacterial genetics, including replica plating, which enabled scientists to isolate and study antibiotic-resistant mutations.

-

Working during the mid-20th century, Lederberg’s groundbreaking contributions were often overshadowed by her male colleagues, reflecting broader gender inequities in scientific recognition at the time.

Quote

“What Lederberg did was spend decades investigating the way micro-organisms share genetic material, trailblazing work at a time when scientists had little sense of what DNA was. So did her first husband…Yet far more people have heard of him than of her, a disparity that some experts attribute to a phenomenon known as the Matilda Effect. The term…described the bias that has led to female researchers being “ignored, denied credit or otherwise dropped from sight” throughout history’.”

-Katy Steinmetz, Time Magazine, April 11, 2019

Early Life and Education

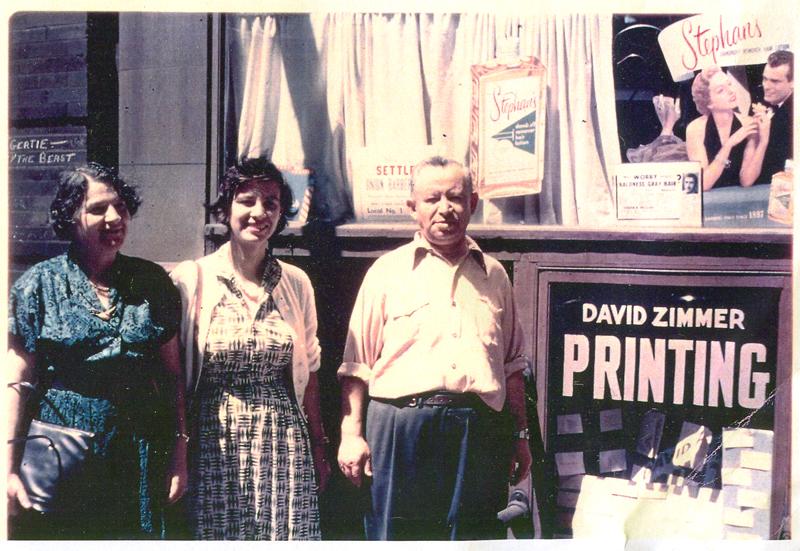

Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg was born on December 18, 1922, in the Bronx, New York, into a working-class Jewish family during the Great Depression. Her father, David Zimmer, was born in Sereth, Bukowina and later immigrated to the Bronx, where he ran a print shop (Marks, 2015). Along with her mother, Pauline Zimmer, he encouraged Lederberg’s intellectual curiosity despite limited financial means. Lederberg recalled that her school lunches consisted of a single slice of bread with tomato juice on top (Das, 2019).

Figure 1, Lederberg and her parent's in front of the printing shop in New York. Photo courtesy of The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust.

Lederberg defied gender norms at a young age. She asked her zayde (Yiddish for grandfather), with whom she had a close relationship, to teach her Hebrew an unusual request, as girls were not typically expected to study Hebrew in Orthodox Jewish traditions. During Passover, Lederberg performed all the readings, which made her grandfather very proud (Estherlederberg.com, n.d.).

Lederberg attended Evander Childs High School and graduated at age 16. In 1938, she earned a scholarship to attend Hunter College, City University of New York. There, she continued to defy expectations by pursuing a degree in biochemistry, despite her teachers warning that such a path would lead to a dead end (Barron, 2023).

She earned her bachelor’s degree from Hunter College in 1942. Two years later, she received a fellowship to attend Stanford University, where she earned a master’s degree in genetics and worked as a teaching assistant (Marks, 2015). At Stanford, she struggled financially and recalled having to eat remains from laboratory dissections to get by. While working in the lab, she studied how bacterial genetics influenced penicillin efficacy (Das, 2019).

By this point, Lederberg had already published three research papers. She met Joshua Lederberg, who would become her husband for the next 20 years. After five months, they married in December 1946. Lederberg continued to publish solo and began collaborating with her husband (Estherlederberg.com, n.d.).

While Joshua pursued his doctorate at Yale University, Lederberg continued her studies at Stanford and worked in the laboratory of George Beadle. She later moved to Wisconsin to join her husband and complete her Ph.D. In 1950, she earned her doctorate in bacterial genetics from the University of Wisconsin–Madison (Pearce, 2006).

Scientific Contributions and Discoveries

Lederberg’s most significant discovery came early in her scientific career. In 1950, while working as a researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, she identified a new kind of virus called lambda phage, which infects E. coli bacteria. She observed that when E. coli strain K-13 was mixed with UV-irradiated strain W-158, some colonies grew irregularly with missing segments. Unlike other phages that destroyed their host, lambda phage inserted its DNA into the E. coli genome and replicated with it—a process now known as lysogeny. This discovery made lambda phage a model tool for studying gene regulation, recombination, and horizontal gene transfer. It enabled breakthroughs in understanding gene expression and the mechanisms of viral latency (What is Biotechnology, n.d.).

In 1952, Lederberg noticed that some E. coli strains couldn’t recombine unless they had a certain component. From this, she hypothesized the presence of a “fertility factor” (F factor), which turned out to be a plasmid. In collaboration with Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, Lederberg confirmed that the F factor facilitated bacterial reproduction by transferring DNA (What is Biotechnology, n.d.).

In addition to the discovery of lambda phage and F factor, Lederberg co-developed the replica plating technique, a method to transfer bacterial colonies from one petri dish to another while maintaining their relative positions. Prior to replica plating, “scientist related on the use of blotting paper and a wire brush with small metal prongs to transfer bacteria between different petri dishes,” (What is Biotechnology, n.d.). Remedies to this problem were often extremely laborious and time consuming, which was when Lederberg came up with a simple solution, a velvet cloth that would “stamp” bacterial colonies from one petri dish to another, preserving their exact arrangement. This also allowed for fast, accurate mutation tracking across many colonies. To test out her idea, Lederberg used a powder puff from her make up bag. This method revolutionized the study of antibiotic resistance, allowing researchers to isolate bacterial mutants without exposing them to antibiotics in the first round of growth, a key methodological shift that supported the theory of natural selection in bacteria.

Barron (2023) reported that Dr. Rebecca Ferrell of Metropolitan State University of Denver noted, “If you go into most microbiology textbooks, [replica plating and the associated discoveries] are credited to Joshua Lederberg.” Ferrell clarified: “No, that was the lady with the knowledge of fabric, [who had been] watching printing presses since she was born.”

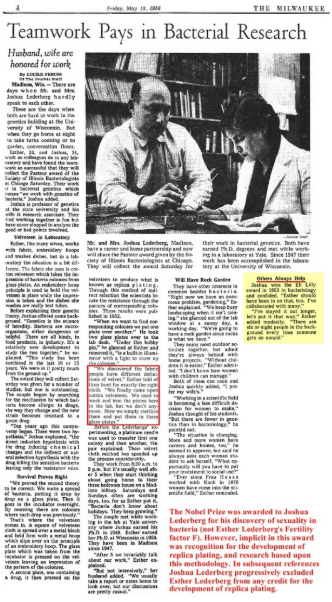

The couple published 12 papers together. In 1956, they were recognized for their bacterial research by The Milwaukee Journal. That year, the Society of Illinois Bacteriologists awarded them the Pasteur Award—the first time it had been given to a research team (Marks, 2015).

Figure 2, An article from The Milwaukee with annotations from the Ester M. Lederberg archive. Photo courtesy of The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust.

Despite her groundbreaking work and sole-authored publications, Lederberg received little formal recognition. During a 1958 press conference, after winning the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Joshua Lederberg attempted to acknowledge her contributions, stating:

In the development of my own work, I feel very abashed to have this attention without mentioning the numerous associates and students and fellows that I've had in my own lab, and the people on whom I've relied on and whose ideas and work have been extremely important. The first among these is my wife, who is my close associate in the laboratory (Estherlederberg.com, n.d.).

Challenges in a Male-Dominated Field

Although Joshua Lederberg received the Nobel Prize, Lederberg was neither included in the award nor credited in many of their collaborative publications (Marks, 2015). After his win, she was expected to play a supporting role, and Joshua only briefly acknowledged her critical discovery of lambda phage (Barron, 2023).

Figure 3, The couple before the 1958 Nobel Prize Ceremony. Photo courtesy of The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust.

This erasure reflected broader patterns in mid-20th century science, where women often played central roles in research but were overlooked in awards and appointments. Joshua became Chair of the Genetics Department at Stanford University, and the couple returned to California. Lederberg was given a senior scientist position but faced limited access to tenure despite her credentials (Barron, 2023). She and colleagues petitioned Stanford’s dean over the lack of women professors. In response, she was offered a position as an untenured research associate professor—a role for which she was overqualified (Marks, 2015).

The couple divorced in 1966, ending their collaboration. Friends recalled that Joshua, who became a prominent figure in the field, often ignored Lederberg after the divorce (Steinmetz, 2019). She continued to struggle professionally at Stanford. In 1974, the university changed her title from Senior Scientist to Adjunct Professor, effectively demoting her (Marks, 2015). According to a friend, Lederberg believed the science would speak for itself, so she did not prioritize seeking credit (Barron, 2023).

Later, Lederberg was invited to curate the university’s collection of plasmids. In 1976, she became the director of the Plasmid Reference Center and played a key role in naming plasmids and the genes they carried. She served as curator until 1986 (Marks, 2015).

Later Career and Legacy

Lederberg retired from Stanford in 1985 but continued to research, write, and support scientists. She returned to her love of opera, which she had enjoyed throughout her life. In 1989, she met her second husband, Simon, in Palo Alto. They married in 1993 and remained together until her death in 2006.

After her death, Simon reviewed Lederberg’s documents and photographs and decided to build an archive to preserve her life and scientific contributions. Thanks to his efforts, and the work of scholars, feminist historians, and scientists, her legacy is now better documented. It serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of recording scientific history that fully recognizes women’s contributions (Steinmetz, 2019).

Reclaiming Her Story

Esther Lederberg’s story exemplifies the need to interrogate how credit is distributed in scientific fields and whose labor is rendered invisible. Her foundational work in microbiology continues to inspire efforts toward equity in STEM.

Her legacy challenges traditional narratives of scientific genius that have centered men while erasing the collaborative labor of women. Lederberg’s life reminds us that scientific progress often emerges not from individual brilliance alone, but from shared knowledge and the uncredited work of those left out of the spotlight.

Works Cited

Works Cited

American Society for Microbiology. (2023, October). Esther Lederberg: Microbial genetics. ASM. https://asm.org/articles/2023/october/esther-lederberg-microbial-genetics

Das, M. (2019, May 20). Esther Lederberg: A forgotten genius. Medium. https://medium.com/young-spurs/esther-lederberg-a-forgotten-genius-923f2ba1414f

Esther Lederberg History Archive. (n.d.). Welcome to the Esther Lederberg website. http://www.estherlederberg.com/home.html#WEBE

Marks, L. (2015, December). Esther Lederberg. What Is Biotechnology. https://www.whatisbiotechnology.org/index.php/people/summary/Lederberg_Esther

Pearce, J. (2006, December 8). Esther Lederberg, 83, scientist who identified stealthy virus, dies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/08/obituaries/esther-lederberg-83-scientist-who-identified-stealthy-virus-dies.html

Piqueras, M. (n.d.). Esther Lederberg and bacteriophage λ. What Is Biotechnology: Antimicrobial Exhibition. https://www.whatisbiotechnology.org/index.php/exhibitions/antimicrobial/index/esther_lederberg#Piqueras

Steinmetz, K. (2019, April 11). She helped discover DNA’s shape but never won a Nobel. Now her work is finally being recognized. Time. https://time.com/5552620/esther-lederberg/

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Style: Analyzing Newspapers

http://www.estherlederberg.com/Censorship2/CensorshipIndex.html.

Caption: An article from The Milwaukee with annotations from the Ester M. Lederberg archive.

Primary Source Inquiry:

-

How does the language of this newspaper article reflect gender bias in the reporting of scientific discoveries?

-

What can we infer about public perception of Esther Lederberg’s work based on her absence or presence in media coverage?

-

How do the annotations on this article reflect frustration with the erasure of women in science?

-

What role do newspapers play in shaping or distorting the legacy of women scientists?

-

Educator Notes:

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts to guide learner inquiry.

Style: Analyzing Photographs & Prints

Picture 1: http://www.estherlederberg.com/Q%20JL%20accepts%20Nobel.html

Picture 2: http://www.estherlederberg.com/Q%20GB%20ELT(left)%20JL(rt)%20at%20NobelPrize%20ceremony.html

Caption 1: Joshua Lederberg accepts the Nobel Prize in 1958

Caption 2: Nobel Prize winners, George Wells Beadle, Edward Lawrie Tatum and Joshua Lederberg

-

Primary source inquiry:

-

What does this photograph reveal about who was publicly recognized in scientific achievements during the 1950s?

-

What clues in the photograph (e.g., composition, who is pictured, attire) suggest the visibility or invisibility of collaborators in major scientific awards?

-

How can we use photographs like this one to question historical narratives about individual versus collective innovation?

-

Educator notes:

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Photographs & Prints to guide learner inquiry.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

-

EstherLederberg.com – A digital archive of her work, correspondence, images, and interviews: http://www.estherlederberg.com/home.html#WEBE

Related Biographies

Related Biographies

How to Cite this Page

How to Cite this Page

MLA – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Esther Lederberg.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Esther Lederberg.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/esther-lederberg