Patricia Bath

Summary

-

Bath developed the Laserphaco Probe, a groundbreaking device and technique for treating cataracts with laser technology.

-

Bath lived and worked during the height of the civil rights movement and fought against racial and gender barriers throughout her career in science and medicine.

Quote

“Do not allow your mind to be imprisoned by majority thinking. Remember that the limits of science are not the limits of your imagination.”

-Dr. Patricia Bath

Early Life and Influences

Patricia Era Bath was born on November 4, 1942, in Harlem, New York City, to Rupert and Gladys Bath. Her father, an immigrant from Trinidad, worked as the first Black motorman for the New York City subway system and nurtured Patricia’s curiosity by teaching her about astronomy and global cultures (Biography). Her mother, a descendant of enslaved Black peoples and of Cherokee ancestry, worked as a cleaner to support Patricia’s education after she entered middle school (The History Makers). Bath later recalled, “My mother was a housewife who worked as a domestic after we entered middle school… She scrubbed floors so I could go to medical school,” (The Lemelson Center).

Bath’s parents instilled in her a deep respect for learning and the importance of education. Her mother supported her budding interest in science by purchasing a chemistry set, while her father inspired her with his love of reading and knowledge of different cultures (Biography). Bath also drew inspiration from Dr. Albert Schweitzer whose humanitarian work in Africa treating leprosy and malaria left a strong impression on her (The Lemelson Center).

While attending Charles Evans Hughes High School, Bath was selected to participate in a National Science Foundation research program at Yeshiva University. Under the mentorship of Dr. Robert Bernard, she conducted cancer research and developed a mathematical equation to predict cancer cell growth. Her work earned her the 1960 Mademoiselle magazine Merit Award and led to the publication of a scientific paper, which she co-authored and presented at a conference on nutrition in Washington, D.C. (Biography).

Figure 1, Bath, in high school, photographed for helping write a cancer study in Washington. Photo credit to Herbert S. Sonnenfeld

Bath completed high school in just two and a half years and enrolled at Hunter College in New York City, where she studied chemistry and physics. She earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1964 and soon afterward entered the Howard University College of Medicine (The Lemelson Center).

Education and Medical Training

Bath graduated from Howard with her M.D. in 1968, one of a small number of women—and an even smaller number of Black students in her class (Biography). She then completed a one-year internship at Harlem Hospital Center, followed by a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University. There, she became the first Black American to train in ophthalmology at Columbia (New York Times).

During her fellowship, Bath observed stark disparities in healthcare access. She noted that Black patients from Harlem were twice as likely to experience blindness and eight times more likely to develop glaucoma than their White counterparts from the Columbia University patient population (Biography). In response to these findings, Bath coined the term “community ophthalmology,” a field that combined public health, patient outreach, and clinical eye care to address disparities in vision health.

Through community ophthalmology, Bath trained volunteers to deliver basic eye care, screenings, and education to under-resourced populations. These volunteers worked with both senior centers and daycare programs, which helped identify preventable vision problems early on for children (National Library of Medicine). In 1968, Bath successfully advocated for her Columbia professors to perform eye surgeries at Harlem Hospital, where she served as assistant surgeon. Thanks to her leadership, the hospital conducted its first major eye operation in 1970 (Changing the face of Medicine).

Around this time, Bath married and gave birth to her daughter, Eraka, in 1972. While balancing motherhood, she continued her medical training by completing a fellowship in corneal transplantation and keratoprosthesis (Changing the face of Medicine).

Breaking Barriers in Ophthalmology

In 1974, Bath moved to Los Angeles and joined the faculty at Charles R. Drew University and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), as an assistant professor of surgery. In 1975, she became the first woman faculty member at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute (Biography). Despite this historic appointment, Bath faced pervasive discrimination. Colleagues excluded her from surgeries and denied her access to lab space. When the eye institute offered her an office, it was in the basement next to lab animals. Bath rejected the placement, stating, “I didn't say it was racist or it was sexist. I said it was inappropriate and succeeded in getting acceptable office space. I decided I was just going to do my work.” (The Lemelson Center).

In 1977, along with Dr. J. Alfred Cannon and Dr. Aaron Ifekwunigwe, she founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness (AIPB). The organization declared that “eyesight is a basic human right” and sought to ensure that access to eye care did not depend on economic status (The Lemelson Center). As director of AIPB, Bath took a sabbatical and traveled internationally, both to escape institutional barriers in the U.S. and to learn from global practices in vision care.

In 1981, Bath studied laser technologies at the Laser Medical Center in West Berlin, the Rothschild Eye Institute in Paris, and the Loughborough Institute of Technology in England (Changing the face of Medicine). This international training informed the invention that would later define her career (New York Times). In 1983, Bath became the first woman to chair an ophthalmology residency program in the United States when she assumed the role at UCLA and Drew University (Black Past). Cataracts are most commonly seen in people over the age of 60 and are the leading cause of Blindness.

During the early 1980s, Bath focused on developing a device that could make cataract surgery more precise and less invasive. Cataracts, a leading cause of blindness, especially among older adults, were typically removed using mechanical tools or ultrasound. Bath envisioned a method that used laser technology for greater precision. Drawing inspiration from advances in cardiovascular surgery, she began work on what would become the Laserphaco Probe (The Lemelson Center).

The Laserphaco Probe and Medical Innovation

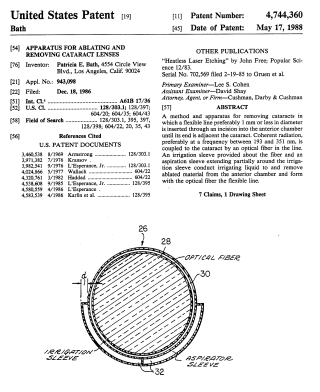

On May 17, 1988, Bath received U.S. Patent No. 4,744,360 for her invention of the Laserphaco Probe, becoming the first Black woman physician to receive a U.S. medical patent (Biography). The Laserphaco Probe used a fiber-optic laser to break apart cataracts through a small incision. An ultrasonic tip further disintegrated the cataract fragments, which were then removed using suction. The device maintained intraocular stability and minimized the risk of complications, revolutionizing cataract surgery (National Library of Medicine).

Figure 2, The first page of Bath's patent.

Bath’s innovation extended far beyond her original patent. She eventually held five U.S. patents, as well as international patents in Japan, Canada, and five European countries. By 2000, her laser device was in use across Italy, Germany, and India, and was later approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (The Lemelson Center).

Advocacy and Global Impact

Throughout her career, Bath remained a staunch advocate for health equity, especially for women and students of color in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). She mentored countless aspiring physicians and scientists and published extensively on topics related to public health, ophthalmology, and global disparities in eye care.

After retiring from UCLA in 1993, Bath continued her advocacy on the international stage. She served as a medical consultant to the World Health Organization and participated in global campaigns to eliminate preventable blindness (The Lemelson Center). Bath also emerged as a vocal proponent of gender justice and equal representation in innovation and medical research.

In recognition of her achievements, Bath received numerous honors. She was inducted into the International Women in Medicine Hall of Fame in 2001,National Inventors Hall of Fame, and the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2024.

Later Life and Legacy

In her later years, Bath continued to innovate. She explored applications of telemedicine to expand access to eye care in rural and underserved communities. She saw the promise of digital health technologies long before their widespread adoption and advocated for systems that could reach patients excluded from traditional care models.

Just two months before her death, Bath was invited to testify before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Intellectual Property in a hearing titled “Trailblazers and Lost Einsteins: Women Inventors and the Future of American Innovation”. During her testimony, she compared her experiences to those of NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson and called attention to the continued exclusion of women inventors. “I call this my Katherine Johnson Moment,” she said, “because my own experience in 1988/1989 mirrored hers… the oversight, slights and disrespect of scientific contributions of women scientists and inventors demonstrated in the 1960’s continues even today.”

Bath passed away on May 30, 2019, from cancer-related complications. Her legacy as a pioneering physician, inventor, and advocate endures. Through her inventions, her writings, and her mentorship, she transformed the field of ophthalmology and carved a path for future generations of women and minoritized scholars in science and medicine.

Works Cited

Works Cited

“Changing the Face of Medicine: Patricia E. Bath.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_26.html.

“Dr. Patricia Bath.” Biography. A&E Television Networks. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.biography.com/scientists/patricia-bath.

“Dr. Patricia Bath.” The HistoryMakers. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/dr-patricia-bath.

“Dr. Patricia Bath, Who Took On Blindness and Earned a Patent, Dies at 76.” The New York Times, June 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/04/obituaries/dr-patricia-bath-dead.html.

“Dr. Patricia Bath: Sights on the Prize.” United States Patent and Trademark Office. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/journeys-innovation/historical-stories/sights-prize.

“Innovative Lives: The Right to Sight—Dr. Patricia Bath.” Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://invention.si.edu/invention-stories/innovative-lives-right-sight-patricia-bath.

“Patricia Bath.” BlackPast. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/bath-patricia-1942/.

“Patricia Bath.” National Inventors Hall of Fame. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.invent.org/inductees/patricia-bath.

“Patricia Bath.” National Women’s Hall of Fame. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/patricia-bath/.

“Patricia Bath: Shake Off the Haters.” ABC News, February 22, 2018. https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Wellness/revolutionary-ophthalmologist-dr-patricia-bath-shake-off-haters/story?id=53357320.

Ramirez, Marina, and Chidubem Nwakama. “Patricia E. Bath (1942–2019): Inventor of the Laserphaco Probe.” The American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports 20 (2020): 100987. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11361739/#REF4.

“Staff.” American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness. Accessed June 23, 2025. http://www.blindnessprevention.org/staff.php.

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

Primary Source Analysis Strategies

https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/trailblazers-and-lost-einsteins-women-inventors-and-the-future-of-american-innovation

Caption: Recording of Bath’s testimony in the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, “Trailblazers and Lost Einsteins: Women Inventors and the Future of American Innovation”.

Primary Source Inquiry:

-

What challenges and barriers does Bath describe facing as a woman—and particularly as a Black woman—in the field of innovation and science?

-

How does Bath use personal narrative, data, or rhetorical strategies to advocate for increased support and recognition of women inventors?

-

What policy recommendations or systemic changes does Bath propose to improve equity in innovation and patent access?

-

In what ways does Bath’s testimony reflect broader societal issues related to gender, race, and access to STEM education and resources?

Educator Notes:

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts to guide learner inquiry.

Analyzing Books and Other Printed Texts

Caption: Bath’s Patent for her Laserphaco Probe

Primary Source Inquiry:

-

What innovative features are described in Bath’s patent for the Laserphaco Probe, and how do they reflect advancements in medical technology during the late 20th century?

-

How does the language and structure of the patent reflect the standards and expectations of scientific and legal documentation at the time?

-

In what ways does this patent represent the intersection of science, technology, and civil rights, particularly regarding access to eye care in underserved communities?

-

What barriers might Bath have faced as a Black woman in science and medicine, and how does this patent symbolize her contributions despite those challenges?

-

How can the Laserphaco Probe be seen as both a scientific innovation and a tool for promoting social equity in health care?

Educator notes:

-

Educators can use Teacher’s Guide: Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts to guide learner inquiry.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

-

Patricia Bath: The Doctor Who Saved Sight by Michelle Lord and illustrated by Alleanna Harris, 2020

-

Interview with Dr. Patricia Bath – The HistoryMakers

Related Biographies

Related Biographies

Carry the Torch

Carry the Torch

How to Cite this Page

How to Cite this Page

MLA – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Patricia Bath.” National Women’s History Museum, 2025. Date accessed.

Chicago – Robledo-Allen Yamamoto, Asami. “Patricia Bath.” National Women’s History Museum. 2025 www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/patricia-bath