Georgia Douglas Johnson

Georgia Douglas Johnson was one of the most well-known Black female writers and playwrights of her time. Known for writing most about love and womanhood, Douglas Johnson’s published works touched many and were featured in the most widely-read Black publications of the twentieth century. In addition to being an active participant in the New Negro Movement, her Washington, D.C. home was also a gathering place for other members of the Black literati to connect and create. In her lifetime, she published 4 books: The Heart of a Woman (1918), Bronze (1922), An Autumn Love Cycle (1928), and Share My World (1962), and won several awards for her contributions to literature, theater, and poetry.

Georgia Blanche Douglas Camp was born on either September 10, 1877 or September 10, 1880, to Laura Douglas and George Camp. Her parents were of African American, Native American, and European descent. Douglas Camp began her education in Rome, Georgia before studying at Atlanta University Normal School. As a child, she was described as being a “teacher’s pet” who relied on the company of her violin to get through her childhood. After graduating from high school in 1893, she began her teaching career in her mother’s hometown, Marietta, before returning once again to Atlanta to work as an assistant principal. Shortly after, Douglas Camp resigned from her assistant principal position to study her first love: music. She moved to Ohio between 1902 and 1903 to study music, harmony, and voice at the Oberlin Conservatory and the Cleveland College of Music (Shockley, 346-347).

On September 28, 1903, Douglas Camp married Henry Lincoln Johnson. Ten years her senior, Johnson was a prominent lawyer from Atlanta and a well-known member of the Republican Party. Within their first few years of marriage, Douglas Johnson gave birth to two sons, Henry Lincoln Jr. and Peter Douglas. In addition to raising her children, Douglas Johnson began to write stories and poems and sent them in to local publications. She also taught and composed music for churches (Shockey, 347). In 1910, her husband was appointed President William Howard Taft’s Recorder of Deeds. Their family in turn moved to Washington, D.C. – a move that changed the trajectory of Douglas Johnson’s life (Poetry Foundation).

After moving to Washington, D.C., Douglas Johnson’s interest in becoming a published writer deepened despite her husband’s desire for her to be a homemaker. Douglas Johnson’s first works in a national publication were published by NAACP’s Crisis Magazine in 1916. Shortly after that, she published her first of two books of poetry, The Heart of a Woman (1918). Douglas Johnson was writing during a growing movement of scholarship and literature about the social and cultural conditions of African Americans. After receiving criticism from readers about her first body of work not being race-conscious enough, her second publication, Bronze (1922), more clearly articulated her experience as a Black woman. Arna Bontemps: “My first book was The Heart of a Woman. It was not at all race-conscious. Then someone said she has no feeling for the race. So I wrote Bronze. It is entirely race-conscious,” (Roses & Johnson 203).

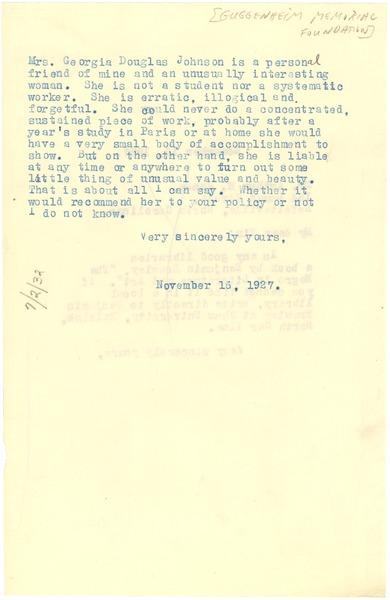

At the height of her career, Douglas Johnson worked with some of the most prominent African American writers. One was W.E.B. DuBois, who she wrote with often and he critiqued her work. In a letter of recommendation from 1927 to an unknown destination, W.E.B. DuBois described Douglas Johnson as someone who “could never do a concentrated, sustained piece of work …] but was liable at any time or anywhere to turn out some little thing of unusual value or beauty.” That “some little thing of unusual value or beauty” was often Douglas’s poems, but was also in the community spaces she created for other African American artists, Washingtonians, and people who were like her in one way or another.

Johnson’s home, located at 1461 S St NW in Washington, D.C. was an important meeting space for Black artists during what writer and philosopher Alain Locke called, “The New Negro Movement.” Historians commonly refer to this period between the 1920s and 1930s as the Harlem Renaissance, when African American thinkers, educators, and artists were embracing racial pride and political freedom through an outpouring of creative contributions. However, Johnson’s weekly salons, sometimes known as “S Street Salons,” showed that these artists who lived, worked, and frequently traveled to D.C. were extensions of a much larger network of twentieth century African Americans both in and beyond New York City. These networks, which were fostered at salons like Douglas’s, inspired some of the most impactful works of the Black literati during this time (Lindsey). She regularly welcomed the likes of Angelina Weld Grimke, Zora Neale Hurston, and Marita Bonner into her home (Hull). Douglas Johnson welcomed the best and brightest of the New Negro Movement into her home and as Washington journalist and poet J.C Byars put it, “If dull ones come, she weeds them out, gently, effectively” (Johnson 496). Douglas Johnson, who was also involved in D.C.’s Negro Little Theatre circles, would read out her one-act plays at her Saturday night salons.

Love and womanhood animated Johnson’s extensive collection of writings, especially as her home and community changed. After her husband died in 1925, she worked to support herself and her two sons. For over a decade, she worked at the U.S. Department of Labor to put her children through medical and law school respectively. She also published another work of poetry, titled An Autumn Love Cycle (1928), and several plays. From 1926 through 1932, she ran a weekly column title “Homely Philosophy,” which was syndicated in over twenty newspapers (Tate, 1997). While many other artists moved from D.C. to New York City to join the growing arts community in Harlem, Douglas Johnson continued to foster her community of artists, writers, and playwrights in D.C. from the Great Depression through the Civil Rights Movement.

George Douglas Johnson wrote through the end of her life and she created countless “little things of value and beauty,” as W.E.B. Dubois noted. She published her final book of 37 poems in 1962, titled Share My World. In 1965, Douglas Johnson was awarded an honorary doctorate in Literature from Atlanta University (Poetry Foundation, Georgia Douglas Johnson n.d.). She was also posthumously inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2010 and is noted as being Georgia’s most famous writer before Alice Walker. She died in 1966 in Washington, D.C. In Ann Allen Shockley’s biography of Georgia Douglas Johnson, she noted: “she confided [to Davis and Freeman, the scholars that wrote her first critical biography] that an appropriate epitaph for her would be ‘she tried.’ She did more than try, however: she succeeded” (351).

- Ann Allen Shockley, Afro American Women Writers, 1746–1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide

- Argueta, et al. “BIOS.” Georgia Douglas Johnson. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://georgiadouglasjohnson.com/georgiadouglasjohnson/.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt). "Georgia Douglas Johnson recommendation." Manuscript. New York (N.Y.), November 16, 1927. Digital Commonwealth, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b038-i397 (accessed May 17, 2023).

- Hull, Gloria T. Color, Sex & Poetry: Three Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

- Poetry Foundation. (n.d.). Georgia Douglas Johnson. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved April 24, 2023, from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/georgia-douglas-johnson

- Roses, Lorraine Elena, and Ruth Elizabeth Randolph. Harlem Renaissance and Beyond: Literary Biographies of 100 Black Women Writers, 1900-1945. Boston, MA: G.K. Hall, 1990. Print.

- Tate, Claudia. Introduction. Selected Works of Georgia Douglas Johnson. New York: G.K. Hall, 1997.

MLA – Cannon, Jasmine Daria. “Georgia Douglas Johnson.” National Women’s History Museum, 2023. Date accessed.

Chicago – Cannon, Jasmine Daria. “Georgia Douglas Johnson.” National Women’s History Museum. 2023. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/georgia-douglas-johnson.

Image credits:

- “Mrs. Georgia Douglas Johnson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-1ece-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed May 17, 2023).

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt). "Georgia Douglas Johnson recommendation." Manuscript. New York (N.Y.), November 16, 1927. Digital Commonwealth, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b038-i397 (accessed May 17, 2023).

- Henderson, Dorothy F. Georgia Douglas Johnson: A Study of Her Life and Literature. Diss. Florida State Univ, 1995. Ann Arbor: UMI Dissertation Services, 2002.

- “Georgia Douglas Camp Johnson.” Dictionary of Georgia Biography. Eds. Kenneth Coleman and Charles Stephen Gurr. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983.

- Stephens, Judith L. Introduction. The Plays of Georgia Douglas Johnson. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 2006.

- Johnson Georgia Douglas Maureen Honey Jimmy Worthy and Cedric Dover. 2023. After a Thousand Tears Poems. Athens: University of Georgia Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=3441140.