Votes for Women means Votes for Black Women

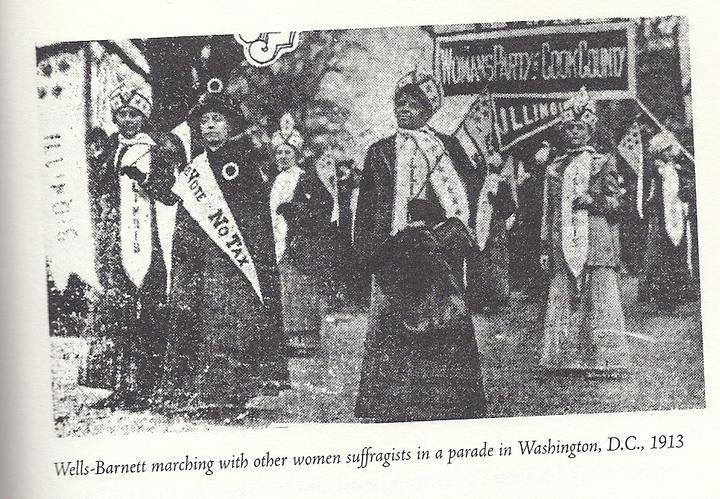

In the lead-up to the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote, images from the 1913 Suffrage March on Washington, D.C. began to make their rounds on social media. In the wake of the 2017 Women’s March, news outlets and bloggers drew visual and ideological comparison between the crowds packing Pennsylvania Avenue. Yet photographs do not tell the entire story. While African American women participated in the march, they are almost entirely absent from event photographs. This is not by accident. Both then and now, African American women have been erased from the narrative of women’s suffrage in America.

Since the mid-19th century, African American women fought for the right to vote while facing discrimination from white suffragists who did not want their movement associated with women of color. Carrying, as suffragist and African American activist Mary Church Terrell said, the “double burden” of Blackness and womanhood, African American women approached the suffrage movement with different objectives than their white counterparts. Painfully aware of the restrictions on Black male voting in the south and the social, political, and economic challenges facing their communities, Black women saw their enfranchisement as an opportunity for community uplift as well as personal recognition of citizenship.

The question of whether “Votes for Women” meant all women or exclusively white women dates to the beginning of the suffrage movement. Though many suffragists were part of the abolitionist movement to end slavery, they were not immune to racial prejudice. Elizabeth Cady Stanton claimed: “it’s better to be the slave of an educated white man than of a degraded black one,” arguing that Black men would be “despotic” if granted the vote. Though Susan B. Anthony believed in universal suffrage, she felt that if only one group were to be given the vote it should be white women. She infamously stated that she would rather “cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the negro and not the woman.” Anthony’s statement, separating women and African Americans into two groups, overlooked the presence of African American women and their desire for the vote. White suffragist anger over Black men’s voting rights further isolated African Americans from the suffrage movement.

African Americans were aware of the suffrage movement’s racism. Yet rather than reject the movement, Black women continued to find ways to be involved in hopes that women’s electoral equality could benefit communities of color. As W.E.B. Du Bois, scholar and editor of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)’s The Crisis put it, “votes for women means votes for black women.” With the vote, Black women could have greater control over “the conduct of educational systems, charitable and correctional institutions, public sanitation and municipal ordinances” where they lived. The promise of social betterment as well as an understanding of what it meant to be deprived of equal rights compelled African Americans to support suffrage.

Despite the almost assured negative reception, many African American women reached out to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and attempted to take part in suffrage activities. While some local chapters of NAWSA were more accepting of Black participation, others were not. In their ongoing efforts to court southern support, northern suffragists held multiple meetings below the Mason-Dixon line. The 1901 and 1903 NAWSA conventions in Atlanta and New Orleans barred African Americans from attending. Attempts by Black women to bring issues impacting their communities to NAWSA’s attention were met with continual rejection. At an 1899 meeting, suffragist Lottie Wilson Jackson tried to introduce a motion for NAWSA to condemn segregated public transportation. The motion was tabled. When Martha Gruening asked NAWSA to denounce white supremacy at the 1911 national conference, president Anna Howard Shaw refused, asserting that while she was “in favor of colored people voting,” she did not want to anger other members of the movement.

In The Crisis, Du Bois challenged suffrage leaders’ racist actions. When NAWSA president Shaw claimed in 1911 that “all Negroes were opposed to woman suffrage,” Du Bois opposed the “barefaced falsehood” and criticized the organization for its poor outreach to Black communities. When Shaw responded, claiming that Blacks were not discriminated against in NAWSA, Du Bois countered with instances of discrimination at the most recent annual meeting. Yet Du Bois encouraged his readers to support the movement, despite its obvious shortcomings. “We tend to oppose the principle [of women’s suffrage] because we do not like the reactionary attitude of most white women toward our problems. We must remember, however, that we are facing a great question of right in which personal hatreds have no place,” Du Bois wrote in 1915. Editorials in The Crisis not only named and shamed suffrage leaders who did not support women of color but warned its readership of regressive views from an otherwise progressive movement.

Shortly after her appointment to NAWSA’s Congressional Committee, activist Alice Paul organized a grand demonstration for women’s suffrage. Having worked in the more radical British suffrage movement before returning to America, Paul understood the power of mass demonstrations. Though she expected to run into difficulties securing permits, navigating the press, and even in recruiting participants, Paul was not prepared for race controversy.

When the Women’s Journal published a letter to the editor asking if there would be Black participation in the parade, Paul requested fellow organizer Hellen Gardner to contact editor Alice Stone Blackwell. Gardner requested that Blackwell “refrain from publishing anything which can possibly start that [negro] topic at this time.” Gardner and Paul feared that after the “very hard fight” to gain permission for the parade, addressing race would cause them to “lose absolutely all we have gained and more.” Paul later told Blackwell, “the participation of negros would have a most disastrous effect” upon the suffrage cause by upsetting southern voters. Parade organizers resolved to “say nothing whatever about the [negro] question, to keep it out of the papers, [and] to try to make this a purely Suffrage demonstration entirely uncomplicated by any other problems.” Instead of viewing Votes for Women as part of a broader push for social equality, Paul separated racial equality from electoral equality.

Nevertheless, Black suffragists rallied. Activists Adella Hunt Logan and Mary Church Terrell encouraged Black women’s clubs across the country to participate. Women at Howard University reached out to Paul, expressing interest in joining the parade. Howard’s Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority president Nellie Quander wrote to Paul, asking to march but expressing concern over rumored segregation. Days before the parade, the state contingent from Illinois telegrammed Paul asking if Black marchers were welcome. Evidently not receiving an answer, the Illinois group and their sole African American participant, the activist and long-time suffragist Ida B. Wells, arrived as an integrated unit.

The question of whether to segregate the parade continued up to the day of the event. Seventy-two hours before the parade, a representative from NAWSA sent an overnight telegram to Paul chastising her for “so strongly [urging] Colored women not to march that it amounts to official discrimination which is distinctly contrary to instructions from National headquarters.” The message ordered Paul to instruct her parade marshals to not exclude Black participants. Still, on the day of the event, African American marchers reported a cold reception. Absentee or uncooperative registry clerks proved an inconvenience. During rehearsal, parade organizers released an official order to segregate, with Black marchers being sent to the back of the parade.

The Illinois unit erupted in debate: would they follow the order to segregate or resist by letting Wells march with their unit? For most of the debate, Wells remained quiet as white women spoke indirectly about her presence. Finally, and with great emotion, she spoke: “If the Illinois women do not take a stand now…then the colored women are lost.” Stirred by Wells’ words, Grace Trout, president of the Chicago Political Equality League, appealed to parade organizers but received a stern reply to segregate. Eventually, “telegrams and protests poured in and eventually the colored women marched according to their State and occupation.” Yet the message was clear: Black women were not fully welcome.

While Wells and other Black suffrage leaders understood the significance of representation on a national scale, Paul did not. Annoyed by African American women’s persistence in their quest for inclusion, Paul wrote “I cannot see… that having this procession without their participation is in anyway injuring them in the least.” She did not understand that executing the largest suffrage demonstration in American history as a segregated affair showed Black women that they were not valued. It delivered a message that Black women, their activism, and their rights did not matter.

While there is no conclusive count of the number of Black suffragists in attendance, historians do know that those who marched represented many states, occupations, and stations in life: teachers, nurses, artists, homemakers, students all stood up for equality. At least four states—Michigan, Illinois, New York, and Delaware—marched as integrated units.

In the chaos of the last-minute segregation debate, Wells slipped away from her unit. Her fellow delegates assumed she had left. Shortly after the parade began, Wells appeared from the crowd and joined her Illinois section, flanked on either side by her friends Virginia Brooks and Bell Squire. A photographer from Chicago’s Daily Tribune captured an image of the triumphant Wells and her colleagues in procession.

The opportunity for a greater political voice drew African American women to the suffrage movement. They supported the movement for its message of gender equality and potential benefits to their own communities while calling out harmful ideologies. Yet making meaningful engagement with mainstream suffrage organizations and leadership proved difficult. From meetings to marches, African American suffragists fought for the vote while fighting white supremacy. NAWSA’s fear of offending southern suffragists, as well as leadership’s own prejudices, silenced Black suffragists and prevented the organization from seriously considering or adopting the intersectional perspectives women of color brought to the movement. Yet Black women were relentless in their attempts to make meaningful engagement with the suffrage movement, not only because they believed in the cause but because they knew it was important that they were present and fighting for their rights both as women and African Americans.

Caraway, Nancie. Segregated Sisterhood: Racism and the Politics of American Feminism. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Clifford, Carrie W. “Suffrage Paraders.” The Crisis, April 1913.

Cook, Coralie Franklin. “Votes for Mothers.” The Crisis, August 1915.

Du Bois, W.E.B. “Along the Color Line: Politics.” The Crisis, April 1913.

Du Bois, W.E.B. “Suffering Suffragettes.” The Crisis, June 1912.

Du Bois, W.E.B. “Votes for Women.” The Crisis, September 1912.

Du Bois, W.E.B. “Woman Suffrage.” The Crisis, April 1915.

Gardner, Helen. “Helen Gardner to Alice Stone Blackwell.” January 14, 1913, National Woman’s Party collection, Group 1, Reel 1, Library of Congress.

Giddings, Paula. Ida: A Sword among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching. New York: Amistad, 2008.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life. New York: Macmillan, 2010.

Hardwick, Marie. “Marie Hardwick to Alice Paul.” January 23, 1913, National Woman’s Party collection, Group 1, Reel 1, Library of Congress.

Hendricks, Wanda A. Gender, Race, and Politics in the Midwest: Black Club Women in Illinois. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998).

“Illinois Women Participants in Suffrage Parade; This State Was Well Represented in Washington.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922); Chicago, Illinois. March 5, 1913.

“National American Woman Suffrage Association to Alice Paul.” Telegram, February 28, 1913, National Woman’s Party collection, Group 1, Reel 1, Library of Congress.

Paul, Alice. “Alice Paul to Alice Stone Blackwell.” January 15, 1913, National Woman’s Party collection, Group 1, Reel 1, Library of Congress.

Paul, Alice. “Alice Paul to Marie Hardwick.” January 28, 1913, National Woman’s Party collection, Group 1, Reel 1, Library of Congress.

Wells, Clara B. “Clara Wells to Alice Paul,” Telegram, February 27, 1913, National Woman’s Party collection, Group 1, Reel 1, Library of Congress

Wilson, Midge, and Kathy Russell-Cole. Divided Sisters: Bridging the Gap between Black Women and White Women. New York: Anchor Books, 1996.

Zahniser, Jill Diane, and Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.