Honoring Rosie the Riveter and the Women Who Won the War

Before World War II, the prevailing view of a woman's role was that of wife and mother. Many occupations divided jobs into “men’s” and “women’s”, a practice reinforced by separate help wanted advertisements. However, the need to mobilize the entire population behind the war effort was so compelling that political and social leaders agreed that both women and men would have to change their perceptions of gender roles—at least during a national emergency. Women were recruited to contribute in variety of ways.

“It’s a Woman’s War Too!” Women Join the Military

After US entry into World War II, Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers introduced a bill creating the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. The WAAC measure allowed up to 150,000 women to volunteer for military service. The armed forces launched crash recruiting drives including rallies, national advertising campaigns, community outreach programs, and appeals to college students.

In 1942, a new law granted women official military status in the Army. Soon after, women joined other uniformed services including the Navy (WAVEs), Air Force (WASPs), and Coast Guard (SPARs).

War Department publicists produced posters and subway cards that portrayed women in uniform as glamorous. The National Advertising Council promised that stories and advertisements for consumer products would promote enlistment in the military and volunteerism at home.

“The Girl He Left Behind is Still Behind Him” – Patriotic Labor Force

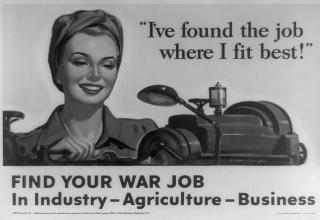

The country had to keep functioning even as millions of men who performed critical functions in the economy were drafted. The departing men left openings in offices and factories across the country at a time when private industry needed to increase industrial production to meet the demand for war materials. Government encouraged private employers to recruit women to open positions and women to accept them. Women responded to calls to keep Americans fed, moving, and communicating.

To help overcome opposition to women in "men's" jobs, campaigns to recruit women workers stressed that production work called for domestic skills. If a woman could sew, she could rivet. If she could put together a pie, she could work on assembly line. Public relations campaigns—even children’s toys—emphasized patriotism, encouraging women to enter the workforce so their husbands, brothers, sons, and fathers could return home sooner.

Women came from all over the country to work in the assembly lines of defense production plants that were converted or built to mass produce ever more sophisticated armaments. Women worked six days a week, enjoyed only a handful of holidays, and were pressed to take overtime to keep the assembly lines operating around the clock. Women who entered war production were primarily working-class wives, widows, divorcees, and students who needed the money. Wages in munitions plants and aircraft factories averaged more than those for traditional female jobs. Women abandoned traditional jobs, particularly domestic service, to work in war production plants offering 40 percent higher wages.

With the help of women workers, total industrial production doubled between 1939 and 1945. The military production was astounding: 300,000 aircraft, 12,000 ships, 86,000 tanks, and 64,000 landing craft in addition to millions of artillery pieces and small weapons.

Women not only took factory jobs, in the cities they took traditionally male jobs such as transit workers and taxi drivers. Women were hired to drive trucks and deliver mail. Professional and technical jobs in radio and journalism, the dominant communications media of the day, opened up to women.

All around the country women stepped into government jobs vacated by men. More than a million women, many of them young and single, came to Washington DC where they became known as “government girls.” As more men were deployed overseas, women—both military and civilian—were admitted into professional classifications previously reserved exclusively for men. By 1944, women accounted for more than a third of civil service jobs. Clerical work was a typical female job in the War Department, and women moved mountains of paper during the war.

“Keeping the Home Fires Burning” Service on the Home Front

Housework and voluntary activities continued to occupy most married women, but these women were not idle. American women had a long history of volunteer civic activism. Women’s organizations provided a nationwide network that mobilized millions of women to implement a wide range of local projects. Women tirelessly gave their time and money with little or no public recognition.

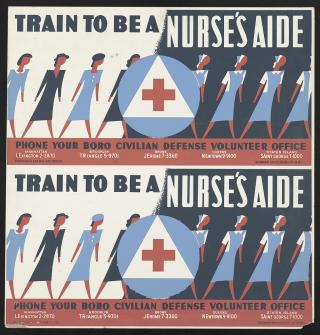

A large number of women’s auxiliary organizations formed spontaneously to volunteer services to the military and civilian civil defense organizations. Members of the largest, American Women’s Voluntary Services, were trained to drive ambulances, fight fires, and provide emergency medical aid in anticipation of aerial bombings that never materialized. Other volunteer military auxiliary groups organized locally.

The Women’s Land Army was organized to deploy volunteers to work on farms and pick crops. Over a million women and girls participated, although wages were low and they had to pay for their room and board.

Almost 100,000 women throughout the country served as unpaid assistants to local rationing boards that distributed coupons based on individual evaluations of need.

Women were encouraged to grow food in Victory gardens and preserve their home-grown vegetables. In 1944, 21 million families planted 7 million acres that yielded 8 million tons of vegetables. Victory Gardens were the answer to concerns about food shortages and the Department of Agriculture promoted growing vegetables.

Women played a prominent role in promoting the sale of war bonds to fund defense production. The General Federation of Women’s Clubs “Buy a Bomber” campaign funded production of 431 planes.

Women contributed thousands of hours to supporting the troops by setting up canteens and rest areas, writing letters, serving as hospital volunteers, and hosting events at military bases.

After the War

The expectation at the end of the war was that things would go back to "normal." Women would be homemakers or revert to traditional female job occupations. And this was true for many women. Thousands of women who would have liked to keep their jobs lost them to returning veterans. But thousands more voluntarily left the workforce to become wives and start families. The marriage rate increased as thousands of couples made up for lost time.

World War II brought significant, lasting changes. Women engaged in traditionally male jobs, and it became more acceptable for married women to work—though not married mothers. Between 1940 and 1945, the female labor force grew to 19 million, more than a third of the American civilian labor force. After the war, women continued to work outside the home. By 1950, women comprised 29 percent of the workforce in the United States.

For many women, World War II brought not only sacrifices, but also new jobs, new skills, and new opportunities. America's "secret weapon" was the women who voluntarily mobilized to meet every challenge. US government and industry expanded dramatically to meet the wartime needs. Women made it possible.

Adapted by Elizabeth L. Maurer from “Partners in Winning the War: American Women in World War II”