The Food Riot of 1917

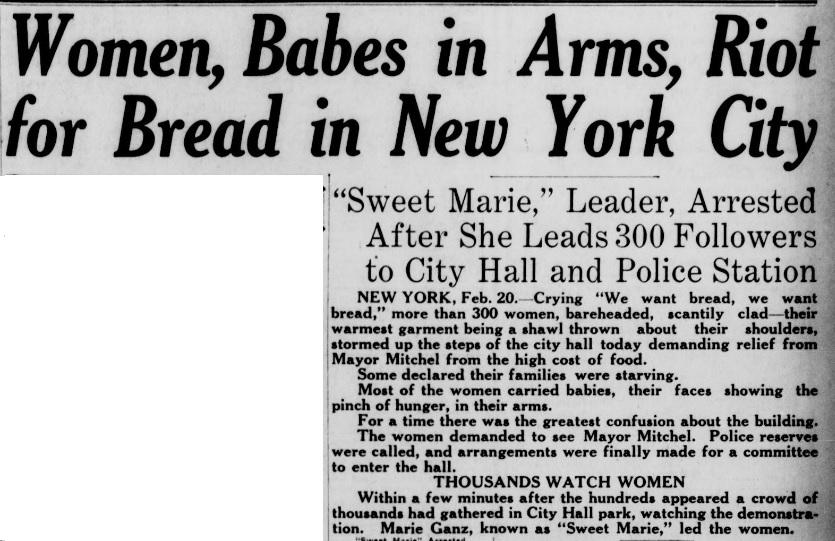

On the morning of February 20, 1917, an army of some 400 angry mothers climbed the steps of New York City’s City Hall. With babies hoisted on their hips, they moved with an urgency brought on by weeks of suffering. “WE WANT FOOD FOR OUR CHILDREN!” they shouted out in English and Yiddish.

A Mayor’s representative peered down at the mob of women from a window and promised to permit three of the protestors to meet with the Mayor if they all went home peacefully. The crowd dispersed. The previous day, February 19, had been a violent culminating point of rapidly growing anger over increased prices on food. After weeks of sharp spikes on food costs, rumors began to ramify throughout New York’s City’s Jewish slums about retailer’s greedy plans to further drive up prices. Women boycotted produce and attacked vendors–lobbing rocks, drenching merchandise in kerosene and assaulting customers who ignored the boycott.

The Seattle Star February 20, 1917

In a time prior to our modern supermarkets, pre-packaged foods and fridges, most families in the early 20th century depended on fresh food and produce from different vendors to feed their families. The responsibility was chiefly a female one and was usually done on a small budget.

One housewife in 1917 noted that “the average cost of preparing dinner for her medium sized family (for dinner alone) in 1916 was .76 cents per meal, or $22 a month, broken down as such:”

- 2 pounds of onions = 6 cents

- 4lbs of potatoes = 8 cents

- 2.5lbs of meat = 40 cents

- 4lbs of bread = 12 cents

- 1/4lb of butter = 8 cents

- 1lb of cabbage = 2 cents

When we consider that the average full-time worker in 1916 was fortunate to make $40 a month and could pay upwards of $15 a month for rent, it helps to put into perspective just how expensive feeding a family could be. And by the beginning of 1917, with the US just months away from entering into World War I, the cost of groceries soared. The average cost for a housewife to make dinner jumped to “$1.99 a meal, or $59 a month:”

- 2 pounds of onions = 40 cents

- 4lbs of potatoes = 28 cents

- 2.5lbs of meat = 60 cents

- 4lbs of bread = 37 cents

- 1/4lb of butter = 14 cents

- 1lb of cabbage = 20 cents

Faced with the reality of hungry children and families, many women were forced to pawn family heirlooms, change their diets, and even cut out meals. Though food costs rose for everyone, low-income families living in districts like the Lower East Side, were some of the hardest hit.

“It used to cost 49 cents to provide breakfast for the four of us. Today the same breakfast would cost $1.02,” one resident told a New York Times reporter in February 1917, adding, “We haven’t had an egg in months and potatoes are a luxury.”

By the beginning of March 1917, wholesalers began to lower prices and New York City began to respond to the food crisis by securing thousands of pounds of low-cost produce.