Defining Designs

I don’t know when the word fashion came into being, but it was an evil day. - Elizabeth Hawes

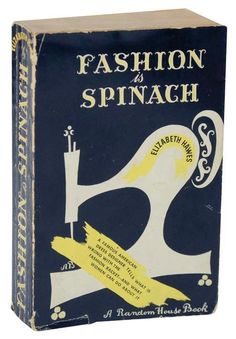

Elizabeth Hawes and Fashion is Spinach

Elizabeth Hawes (1903-1971) famous declaration, encapsulated her complicated relationship with the fashion industry. Educated at Vassar, Hawes enjoyed a diverse career that took her from being a copyist in the haute couture salons of Paris in the 1920s (also known as a “design thief,” Hawes would sketch the latest French fashions to be copied back home by American companies), to being a successful designer in her own right in the 1930s and 1940s. Constant through her lifetime were her roles as a journalist, an insightful author, a sharp commentator on the fashion industry and an outspoken, politically-engaged advocate for women’s rights. Hawes launched her namesake line in 1930, quickly earning a reputation for innovative and witty fashions, which she gave irreverent names, including her “Alimony” and “The Tarts” dresses and her famous “Guardsman” gloves. By 1940, Hawes had largely retired from the fashion industry, however what continued were her polemics on fashion and style. Indeed, what has most defined Elizabeth Hawes’s legacy is her fashion writing, particularly her first book, Fashion is Spinach.

Fashion is Spinach was published in 1938, with its title stemming from a New Yorker cartoon that sees a young boy looking unimpressed with his plate of spinach, and although his mother implores him to eat, the boy responds, “I say it’s spinach. And I say, the hell with it.” Fashion is Spinach sees Hawes outline why, to her, the fashion industry resembled that unappealing plate of spinach; using her own professional experiences to critique the way fashion was marketed and sold to women. Chiefly among Hawes’s concerns was the important difference between fashion and style. To Hawes, style was about honing an authentic, appropriate, personal look; style was “that thing which, being looked back upon after a century, gives you the fundamental feeling of a certain period in history… Style gives you shorts for tennis because they are practical. Style takes away the wasp-waisted corset when women get free and active.” In contrast, “Fashion is that horrid little man with an evil eye who tells you that your last winter’s coat may be in perfect physical condition, but you can’t wear it. You can’t wear it because it has a belt and this year ‘we are not showing belts.’” Hawes loathed the industry’s incessant pressure for “newness” and, as fashion historian Valerie Steele has noted, held the belief that simply: “You should feel free to wear whatever makes you happy.” Hawes’s also addressed French versus American fashion, at a time when Paris still dictated the fashion agenda. “The difference between French and American style is not very great,” Hawes wrote, “But just enough to make many French designs useless for the United States.” Hawes opened her own line in the hope of questioning the “French Legend” and instead championed homegrown talent and encouraged the American fashion industry to create clothing accessible to all American women that actually suited their lifestyles.

Fashion is Spinach provides not only an important insight into the fashion industry in the 1920s and 1930s, but highlights a number of issues that would inform the changing landscape of the American fashion industry for much of the twentieth century.

Vera Maxwell and the “Weekend Wardrobe”

Having enjoyed early careers as a ballet dancer and a fashion model in Manhattan, Vera Maxwell (1901-1995) transitioned into fashion design, where both her practical tailoring abilities and her intuitive good taste found their greatest expression. A key figure in the creation of the “American Look,” Maxwell established a reputation for quality American sportswear separates, impeccable suiting and timeless dresses, as well as designing the “Rosie the Riveter” coveralls as part of the war effort (the predecessor to today’s ever-popular jumpsuit).

Vera Maxwell 1958 design

In 1935, Maxwell outlined her design approach as, “Evolving basic silhouettes which are actually studied and precisely fitted but at the same time convey the casual appearance to essential to successful sports clothes.” This encapsulates Maxwell’s legacy: fashions that have an effortless quality but which are carefully thought out and imbued with all the “newness” of the moment, including innovative fabrications (with early forays into Arnel and Ultrasuede), perceptive solutions (in 1975 Maxwell unveiled her “Speed Suit,” a dress with no fiddly fastenings that could be put on in seconds), and unexpected detailing (like lining a jacket with the same fabric as its matching dress).

While Maxwell’s designs are most commonly described as “timeless” and “classic,” she was extraordinarily forward thinking in meeting the changing demands and lifestyles of women. She offered a range of sizes beyond a size 8 when that was unusual and as Richard Martin has noted, Maxwell “never forgot that women were going to be active and working, and she realized more than anyone that air travel was going to be the quintessential experience of the late 20th century.” It was her early recognition of the need for convenient, stylish, versatile fashions for women on the move that gave rise to one of her most famous design innovations: The Weekend Wardrobe.

The “Weekend Wardrobe,” introduced in 1935, was a collection of coordinated garments that could be mixed and matched at will and easily packed for a weekend jaunt. The first Weekend Wardrobe included a collarless, Harris tweed jacket (inspired by one Maxwell saw Albert Einstein wearing at Princeton in 1935), another jersey jacket, pants and two skirts. Emblematic of her powers of “experience and observation,” Maxwell created the kind of coordinated, streamlined collection that she, or any woman, would find easy to take and wear on a short trip.

Maxwell also established the blueprint for effortless separates dressing that would define American fashion for generations. In fact, as the rest of the fashion world caught up with her idea, Maxwell continued to develop her convenient, stylish answer to the traveling woman’s needs. In 1946, Maxwell tested out her capsule weekend wardrobe for air travel (weighing in under the 55lb personal packing limit) and in 1948 she offered a Donegal tweed jacket with oversized pockets that were lined in plastic to carry all the washbag essentials. Maxwell also deftly employed Arnel to make pleated skirts that could survive the crush of a suitcase, and in 1975 she created yet another version of her weekend wardrobe to fit inside a single carry-on garment bag made with the latest, travel-friendly fabric Ultrasuede.

In a career filled with pioneering design moments and timeless fashions, Maxwell’s Weekend Wardrobe defined American sportswear separates dressing and fully achieved her mission to create “easy and attractive clothes for women who worked, traveled and led active lives.”

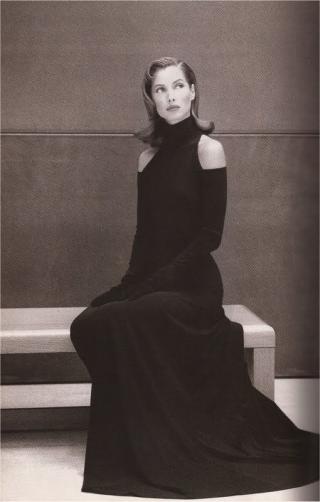

Donna Karan and the Cold Shoulder Dress

“For me, designing is an expression of who I am as a woman, with all the complications, feelings and emotions,” Donna Karan (b. 1948) once explained. From her iconic sensual, jersey gowns and sleek, stretchy bodysuits, to her versatile wrap-and-tie skirts and practical, professional suiting, Karan has spent her career creating beautiful and functional clothing for every aspect of a woman’s life. Working her way up through the ranks at Anne Klein before starting her own line in 1985, Karan follows in the rich tradition of female American fashion designers who created clothing that not only fulfilled needs in their own lives, but in the lives of women everywhere. Karan’s designs showcase a thoughtful balance between beauty, art, comfort, power, luxury, sensuality and, above all, practicality. Karan launched her line with her “Seven Easy Pieces,” which was a capsule collection of coordinating, interchangeable garments that could transform one’s look and create stylish outfits anywhere, anytime. However, of all her designs, it is perhaps the Cold Shoulder dress of the early 1990s that has become most iconic.

Donna Karan cold shoulder dress

Debuting in 1992, Karan’s cold shoulder dress was a sleek, black, matte jersey dress, with long sleeves, a high neckline and deep cutouts at the shoulders to expose the skin beneath. Karan felt that this cut-out silhouette, in a bodysuit, top or dress, lent itself well to her established system of dressing, as she explained, “What I love about it goes back to my original concept. Wear it under a suit and it looks like a turtleneck. Wear it at night without the suit and it’s totally different.” However, Karan also emphasized its almost universal flattery: “A woman never gains weight in her shoulders, so everyone is happy to bare them.”

Although the dress initially received a cool reception from the fashion world, when First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton wore the dress to the Governors Dinner in 1993, one of her first official engagements in her new role, the cold shoulder dress became a hot topic. At a moment when all of America, and the world, was looking to see how Clinton would juggle her roles as a wife, mother, leader of health-care reform and as First Lady, fashion took center stage. So began, as writer Alice Hines, has observed, “a tradition of (often sexist) HRC outfit commentary still going strong 23 years later.” National media outlets mused on everything from the traditional connotations of a lady’s exposed shoulder (“A bare shoulder radiates demure sexuality, like Grace Kelly’s in To Catch a Thief,” suggested Hal Rubenstein in the New York Times, “It conjures up images of a stolen nuzzle in a hansom cab, the sweetness of prom night. It’s a great roadside stop on the way from the neck to the breast”), to how the dress helped a concerted effort to reframe Clinton’s public image by emphasizing her role as First Lady, and all its associated responsibilities in the White House, first and foremost. The conversation was heightened all the more given Karan’s status as a designer who unashamedly championed the idea that a woman could be more sensual in her style and still convey power, confidence and capability. The cold shoulder dress followed hot on the heels of Karan’s most openly feminist advertising campaigns in 1992, which resulted in one of the most iconic fashion images of all time: A model dressed in Karan-designed pinstripes and pearls being sworn in as president surrounded by American flags and gentlemen, with the campaign line simply written below: “In Women We Trust.”

The cold shoulder dress has come to stand not only as a masterclass in Karan’s approach to form, fabrication and sensuality but as a touchstone for the myriad of attitudes and public media negotiations regarding a woman’s place in the professional, political and private spheres of life in the early 1990s.

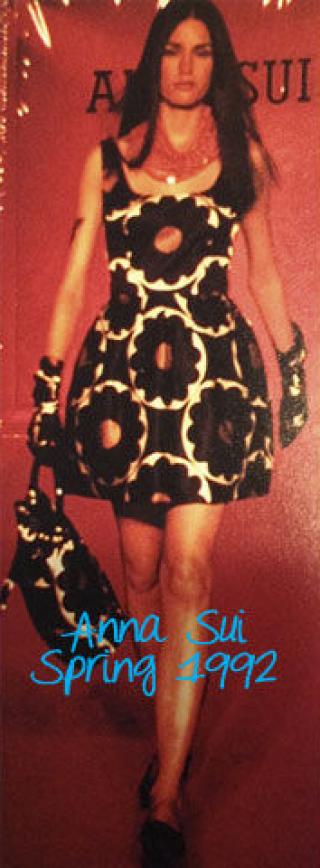

Anna Sui and the “Barbie & Lady Diana Cooper” Collection, Spring Summer 1992

Anna Sui, born 1964, is an American fashion designer, known for her witty and whimsical fashions and her global lifestyle brand. Born in Detroit, Sui graduated from Parsons in 1986 and debuted her first collection in 1991. Since then, Sui has earned a reputation for glamorous “boho” style, diverse cultural references (cowboys, 1930s Hollywood starlets, Seventeen magazine, Busby Berkley musicals to name a handful), vivid colors, unusual fabric choices and for the unique ability to romp nostalgically through different historical time periods while still creating clothing that feels current (particularly favoring 1960s London, 1970s disco, 1990s Paris and Victoriana).

Anna Sui design

Sui is also synonymous with Americana, frequently co-opting hallmarks of classic American preppy style; reimagining Bermuda shorts, Liberty-print Villager dresses, or cable-knit sweaters for her own playful world. Importantly, Sui deftly weaves her own life, experiences, memories and nostalgia through her work. One collection that defines many of the key motifs and themes that recur throughout her career, and which places her work in the broader scheme of American fashion history, is Sui’s Spring/Summer 1992 collection.

Spring/Summer 1992 drew its central inspiration from two figures: Barbie and Lady Diana Cooper, a beautiful British socialite. As Andrew Bolton has observed, these are “figures who reflect two enduring and dichotomous influences in Sui’s work – American popular culture and English aristocratic traditions.” As such, the collection could be described as “Sophisticate Barbie:” crisp white and navy striped jackets, shorts and sleek overall dresses created a youthful freshness that contrasted with Sui’s grown-up, sensual lace babydoll dresses; while bold, oversized-gingham crop-tops were tamed when paired with matching, demure pencil skirts. There was even elegant suiting, inspired by the French couture traditions of Chanel and Balenciaga.

Testament to Sui’s deeply personal approach to design, these varied inspirations also form a commentary on her youth and experiences: As a child, Sui made clothes for her Barbies and she featured some of the ensembles she so vividly remembered, and she used a vintage Balenciaga advertisement she had kept for her take on suiting.

Above all, the collection shows what would become Sui’s enduring deference to the traditions of America’s most influential fashion designers, particularly those responsible for the “American Look” in the 30s and 40s. Following in the footsteps of sportswear stars Claire McCardell and Anne Fogarty, Sui used every day, casual fabrics, like denim and cotton piqué, to create imminently wearable clothes, including denim jeans, rolled at the ankles for the ultimate relaxed look, and simple, nipped-waist cotton dresses.

When the New York Times reviewed the collection, they wrote, “The first number out set the mood. It was a blue and black gingham shirtdress with a full, calf-length skirt. Sounds like the 1950’s, right? But the skirt was left open to show matching shorts, and the model’s head was encased in a towering black straw hat.”

Indeed, Sui used the vocabulary of American sportswear to speak a new language, as she explained, “You can’t just pull a concept out of nowhere and say this is the look of today, because it doesn’t happen that way. Fashion is a reflection. […] You have to bring it back so that a person can walk down the street and not look like she walked out of a costume epic or a time machine. It’s got to fit into how people are dressing today.”

The Spring/Summer 1992 collection, then, sets a precedent for the way in which Sui blends inspirations from seemingly disparate worlds and eras, explores nostalgia and personal experience and delivers innovative design with a firm grasp on the traditions of fabrication and style in American fashion history.

- Bolton, Andrew. Anna Sui. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2010.

- “Cold Shoulder.” Women’s Wear Daily, Feburary 2, 1993.

- Cotier, Virginia. “Designers of Today and Tomorrow: Vera Maxwell.” Women’s Wear Daily. October 30, 1935.

- “A Designer Packs for her Own Flying Weekend Wardrobe.” Women’s Wear Daily. April 12, 1946.

- Hawes, Elizabeth. Fashion is Spinach. New York: Random House, 1938.

- Hines, Alice. “Donna Karan and the First Female President.” The Cut, October 25, 2015.

- Karan, Donna. My Journey. New York: Ballantine Books, 2015.

- Karimzadeh, Marc. “Donna’s Iconic Moments.” Women’s Wear Daily. January 11, 2007. 9.

- Kirkham, Pat and Kohle Yohannan. “Vera Maxwell.” In Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century edited by Susan War, 422-423. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Klemesrud, Judy. “Good News for ‘Vera’s Ladies.’” New York Times. October 21, 1970.

- Martin, Richard. American Ingenuity: Sportswear 1930s-1970s. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

- Morris, Bernadine. “Timeless Fashions at a Vera Maxwell Retrospective.” New York Times, December 12, 1980.

- Ozzard, Janet. “Vera Maxwell Remembered.” Women’s Wear Daily, January 23, 1995.

- Quinn, Sally. “Look Out! It’s Superwoman.” Newsweek. February 15, 1993.

- Rubenstein, Hal. “THING; The Cold Shoulder.” New York Times. February 7, 1993.

- Schiro, Anne-Marie. “Collection by Sui Spans the Decades.” New York Times, April 13, 1994.

- Schiro, Anne-Marie. “Nostalgia With a Look That’s Now.” New York Times December 1, 1991.

- Schiro, Anne-Marie. “Vera Maxwell is Dead at 93; Legendary Sportswear Designer.” New York Times, January 20, 1995.

- Sheppard, Eugenia. “Olympic Uniforms Inspire Vera Maxwell’s ‘Speed Suit.’” The Toledo Blade. March 11, 1975.

- Spindler, Amy M. “Behind the Seams.” New York Times Magazine, November 14, 1999.

- Steele, Valerie. “American Fashion.” In Women Designers in the USA, 1900-2000: Diversity and Difference edited by Pat Kirkham. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Steele, Valerie. Women of Fashion: Twentieth Century Designers. New York: Rizzoli, 1991.

- Warren, Virginia Lee. “Vera Maxwell: Timely Yet Timeless Fashion: Designer’s Creations Remain Wearable Year After Year.” New York Times. November 25, 1964.

- Wilson, Eric. “Now You Know: The Evolution of Donna Karan’s Seven Easy Pieces,” InStyle, July 1, 2015.