The WAVES Of World War II

(Color) USS Missouri (BB-63)Aug 1944

(Color) USS Missouri (BB-63)Aug 1944National Archives, Record Group 80 | National Women’s History Museum

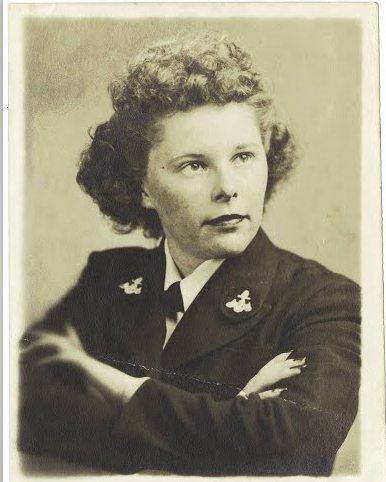

Jaenn Coz Bailey (1945)

Jaenn Coz Bailey (1945)by Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, UNCG University Libraries National Women’s History Museum

A Long Journey

Placed on a troop train, Jeann Coz Bailey traveled across the country to attend recruit training at Hunter College in New York. Unable to bathe and hardly able to use the restroom, Jeann sat on the train for six days, making the arduous journey from Sacramento to the Bronx. Arriving in the fall of 1944, the California girl was no match for the frigid East Coast weather: “Here we come, stepping out of the train in three inches of snow in our little civilian shoes and our little California clothes. . . I was freezing to death, marching through the damned snow ankle-deep.” Jeann was one of the nearly 100,000 women who left the comfort of their civilian life to serve in the Women's Navy Reserve (WAVES) during World War II. By July 1945, over 86,291 women were members of the Navy WAVES, including 8,475 officers, 3,816 enlisted, and 4,000 recruits. They served in a wide variety of roles, ranging from clerks to top-secret code breakers. Essential to the war effort, the WAVES of World War II helped to lay the foundation for future women's future service in the Navy

Nurses in Cuban waters during the Spanish-American War

Nurses in Cuban waters during the Spanish-American War1898 Naval History and Heritage Command | National Women’s History Museum

Women in the Navy before World War II

Prior to the First Wold War, nursing was the only service option permitted for women in the United States Navy. The role of women in the Navy broadened in 1916 with the passage of Public Law 241, which stated that any U.S citizen could serve in the Navy. As a result, 11,000 yeomen served along 1,713 nurses, and 269 female Marines during World War I.In the days following the Pearl Harbor attacks of December 7, 1941, the Navy began debating the integration of women in the Navy. With reluctance, opinions began to change after the newly created War Manpower Commission declared itself unable to meet projected naval expansion. In short, the Navy needed women to assist in the war.

Public Law 689 Jun 30, 1942

Public Law 689 Jun 30, 1942 Library of Congress | National Women’s History Museum

World War II and the Beginning of the WAVES

Public support for the inclusion of women in the armed forces heightened throughout 1941. Advocates argued that women had the right to exercise all responsibilities and duties of citizenship. As pressure mounted, Congress created the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) on March 15, 1942. Nearly five months later, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Public Law 689 on July 30, 1942, creating the Women’s Naval Reserve. The law intended to “expedite the war effort by releasing officers and men for duty at sea and their replacement by women in the shore establishment of the Navy, and for other purposes.” Under Public Law 689, women did not serve on the front lines; they took over roles on the home front, freeing men to serve in active combat. Unlike the WAACs, which functioned as a supplemental branch to the Army, the Women’s Naval Reserve was an integrated part of the Navy.

Lieutenant Commander Mildred H. McAfee, USNR

Lieutenant Commander Mildred H. McAfee, USNR 1942 - 1943 National Archives, Record Group 80 | National Women’s History Museum

Although the Navy agreed to enlist women, disputes regarding the circumstances and conditions of enlistment remained. The Navy decided to bring some of the most intelligent women in America together to form the Advisory Council for the Women’s Reserve. Headed by Dr. Virginia Gildersleeve of Barnard College in New York, the women on the Advisory Council did not have naval backgrounds. Instead, they led some of the best women’s colleges in the country. They knew how to educate women and advised the Navy on the best methods for training women; how to recruit the best candidates; and how to instill discipline. The Advisory Council selected the first director of the WAVES, Wellesley College President Mildred McAfee. After obtaining a leave of absence from Wellesley president, McAfee became the first female naval line officer in American history.

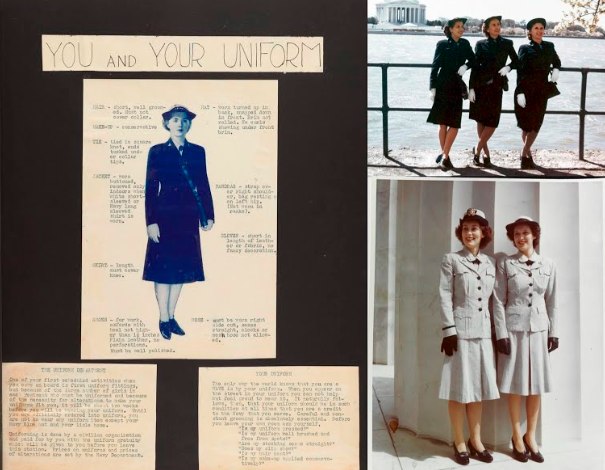

Navy WAVES in Uniform

Navy WAVES in Uniform 1942 - 1944 Harvard University, Elizabeth Reynard Papers and National Archives | National Women’s History Museum

Uniforms

The Advisory Council also helped design the Women’s Naval Reserve Navy uniform. Wanting a functional and fashionable design, they selected a fitted jacket, skirt, and heeled shoe as the final uniform. Why not pants? It maintained a clear distinction between women and men. The women in the WAVES wore their uniform with pride. The uniform made things “very much easier because you didn't ever have to worry about what to wear. . . you were dressed for any occasion,” remembered a former WAVE. Another recalled the only problem being the footwear: “regular oxford, ties and all. It wasn’t the least bit becoming, but we suffered through it.”

Elizabeth Reynard from Barnard College

Elizabeth Reynard from Barnard Collegeby Jericho House, Dennis Historical Society, Dennis, MA. National Women’s History Museum

The Women’s Navy Reserve did not have an acronymic name at first. When one newspaper laughably called the Women’s Reserve “sailorettes,” Naval officers ordered Elizabeth Reynard, second in command of the Women’s Reserve and Advisory Council member, to select a better name. In her autobiography, she describes how she intended to come up with a name that was “nautical, suitable, fool proof and easy to pronounce.” She knew she needed to include a “V” for volunteer because the Navy wanted to make it clear that it was a voluntary and not a drafted service. She also needed to include a “W” for women. “I played with those two letters and the idea of the sea and finally came up with ‘Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service; – W.A.V.E.S. I figured the word Emergency will comfort older admirals, because it implies that we’re only a temporary crisis and won’t be around for keeps.”

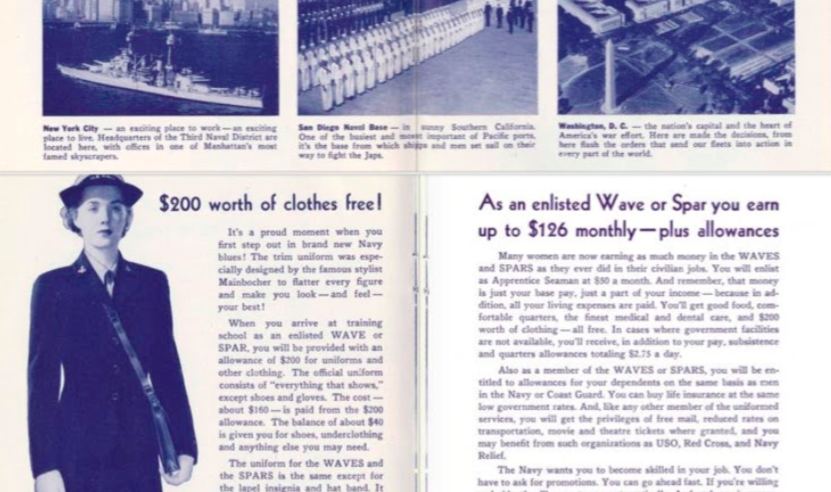

Page from recruitment pamphlet, "How to serve y... (Dec 18, 1942)

Page from recruitment pamphlet, "How to serve y... (Dec 18, 1942)by The University of North Carolina Greensboro, Women Veterans History Project National Women’s History Museum

Eligibility

Eligibility for the WAVES program was selective. For officer candidate school, women were required to be between the ages of 20 - 40, possess a college degree, or have two years of college and two years of other professional experience. For eligibility into the volunteer program, women needed to be between the ages of 20 and 35, possess a high school or business diploma, or have other equivalent experience.

Pages from recruitment pamphlet, "How to serve ... (Dec 18, 1942)

by The University of North Carolina Greensboro, Women Veterans History Project

National Women’s History Museum

Pages from recruitment pamphlet, "How to serve ... (Dec 18, 1942)

by The University of North Carolina Greensboro, Women Veterans History Project

National Women’s History Museum

Collage of Navy WAVE recruitment posters (1942 - 1945)

Collage of Navy WAVE recruitment posters (1942 - 1945)by National Archives, Record Group 44 National Women’s History Museum

Recruitment

Seeking educated women to join its ranks, the Navy placed propaganda posters throughout college campuses and nearby towns. These recruitment posters typically emphasized equity between men and women. As a Navy recruit, women would receive the same pay, follow the same traditions and rules, and conduct the same work as their male counterparts.

WAVES Recruitment Visit (1942 - 1943)

WAVES Recruitment Visit (1942 - 1943)by National Archives, Record Group 69 National Women’s History Museum

Naval recruiters also visited college campuses to meet potential recruits, and many women joined the Navy as a result of these visits. Mary Ada Cox Dunham was one of the college women who joined after a recruiter's visit. She recalls being in a “huge auditorium at UNCG, and a darling girl came out in her WAVE uniform, a little blonde, cute as she could be. She was a recruiter. I think I made up my mind that minute that that is the way to go.”

Application for Commission in U.S Navy (Jul 31, 1942)

Application for Commission in U.S Navy (Jul 31, 1942)by National Archive, Record Group 24 National Women’s History Museum

Meanwhile, Jeann Bailey had grown restless after graduating high school in 1943. Her high school sweetheart was drafted before he had even graduated high school, along with all of her male friends. While walking down a Sacramento street one evening, “fog just [came] down to the ground, and all of a sudden, I saw this mail truck come by and Uncle Sam said, ‘The navy needs you.’ I thought, well, you know, I'll just go in and see. I'm bored to death anyway.” With that, she began the proper paperwork to enlist in the Navy. The WAVES program required all young under the age of 21 to get their parents’ permission. Only 20 and a half at the time and knowing that her parents would not approve of her enlisting, Jeann Bailey got her mother to sign the permission slip by saying that it was an insurance policy. By October 1944, she was on her way to recruit training at Hunter College.

Collage of Naval Training School, Yeoman-W, Mil... (Apr 1945)

Collage of Naval Training School, Yeoman-W, Mil... (Apr 1945)by National Archives, Record Group 80 National Women’s History Museum

Training

The Navy contracted numerous college campuses such as Georgia State Women’s College to open their doors and serve as WAVES recruit training grounds. There, recruits received about two months of intensive general training, where they learned naval terminology, traditions, regulations, and drills. After recruit training, WAVES members received specialized training on other campuses and naval facilities. While most women were trained to serve in clerical roles, many women received training to become radio operators or storekeepers. Later in the war, WAVES received training in other specialized professions typically held by men, including finance, chemical warfare, and aviation ordnance

WAVES Training at Smith Center (1946) by National Archives, Record Group 181

National Women’s History Museum

WAVES Training at Smith Center (1946) by National Archives, Record Group 181

National Women’s History Museum

Smith College was the first campus to host female Naval officer recruits. Due to its location in Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College was nicknamed the USS Northampton.

Naval Training Center, Women's Reserve, The Bro... (1943)

Naval Training Center, Women's Reserve, The Bro... (1943)by Naval History and Heritage Command National Women’s History Museum

Training at Hunter College

Basic training at Hunter College in Bronx, New York represents the type of training WAVE recruits received. The daily routine included waking up at 5:30 a.m. and breakfast at 6:30 a.m. WAVES attended classes and drill for four hours before and after lunch. Most had an hour of free time in the afternoon before dinner. The recruits had two hours of study or class after dinner. After, they had 10 p.m. taps. “The schoolwork, the classes were rather difficult because they were absolutely pouring it to us as fast as they could go. And we didn't have time to study, so what you absorbed as you were going along was what you got,” reminisced a former WAVE. “We had to go to classes. We had identification classes of ships, aircraft. We had to know all the rules and regulations of the navy. We drilled for hours, and every Saturday morning we had a full-dress review… That was quite an experience. I mean, we had to be precision,” said another.

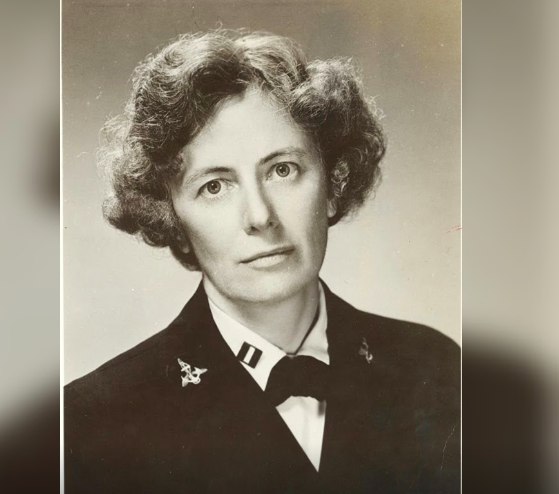

Portrait of Jeann Coz Bailey 1945

Portrait of Jeann Coz Bailey 1945Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, UNCG University Libraries | National Women’s History

Active Duty WAVE

In December of 1944, Jeann was whisked from Hunter College and sent to Washington, D.C. As a former librarian for the California State Library, Jeann was one of five women at the Naval Communications Annex who typed and filed top-secret decoded messages. She also helped organize a library of classified materials, and delivered dispatches to the White House. Like all WAVES, Jeann Bailey functioned as an integral part of the war effort. Working under security clearance, she regularly delivered top-secret dispatches directly to the President of the United States. “Nobody touched that dispatch but the Presidents.” Bailey and the other women in her unit worked directly on the dispatches and personally knew the content. Operating under a high level of secrecy, she often knew about advancements in the war effort before the government publicly announced them. “We knew the war was over three days before it was. We knew so many more things than the public did before it ever happened, but the President didn't

Yeoman 1st Class Marjorie Daw Adams, USNR(W) (1945)

Yeoman 1st Class Marjorie Daw Adams, USNR(W) (1945)by National Archives, Record Group 80 National Women’s History Museum

Challenging Discrimination

WAVES often faced sexism, harassment, and discrimination during their service. At times, male ensigns would order WAVES to perform tasks attributed to domestic life and not in their job assignments. The women in Jeann Bailey’s unit were often asked to mop floors. Luckily, her commander stepped in, stating “My girls don't mop floors." The ensigns argued that the unit was top security; only someone with top clearance could mop there. The commander responded, "Me and my officers will mop the floors." After that, “there were about thirty guys, all officers, and they all mopped the floors in our section.”More severe forms of discrimination also occurred. One WAVE recalled, “I had a lieutenant who wanted me to go out with him…He made my life miserable.” When she started dating someone else, he discharged her. Many men in the Navy resented the WAVES. “They resented us. They resented us for the fact that they had to clean up their act in the crew’s room and they had to quit using bad language,” remembered former WAVE Rosemary Dodd.

Four WAVES laughing (1945)

Four WAVES laughing (1945)by The University of North Carolina Greensboro, Women Veterans History Project National Women’s History Museum

Recreation and Free Time

Working in three shifts a day, normal nine-to-five schedules did not exist for these women. When WAVES did have a brief moment of free time, they spent it enjoying their new surroundings. Among other things, WAVES dated, picnicked, visited museums, and went dancing.

Collage of WAVE jobs (1942 - 1945)

by National Archives, Record Group 80 and Naval History and Heritage Command

National Women’s History Museum

Collage of WAVE jobs (1942 - 1945)

by National Archives, Record Group 80 and Naval History and Heritage Command

National Women’s History Museum

The Navy’s WAVES performed various tasks in multiple fields. They served as clerks, recruiters, mechanics, parachute riggers, aerographers, hydrographers, cryptologists, air traffic controllers, archivists, aviators, accountants, and nurses. They worked in hospitals, stores, mailrooms, photo labs, offices, libraries, air stations, training bases, among others. The bold women who served in the WAVES advanced the status of women in the Navy and worked assignments previously unassigned to women. Women like Elsa Hopper, who served as the Navy’s only female nautical engineer, pushed the perceived limits of what women were capable.

V-J Day in New York City. Crowds gather in Time... (Aug 15, 1945)

V-J Day in New York City. Crowds gather in Time... (Aug 15, 1945)by National Archives, Record Group 111 National Women’s History Museum

Legacy and Effect

The WAVES represent a fundamental shift in American society. Women were moving from the home into the workforce, gaining increased independence. They met people from all over the country, exposing themselves to new ideas, customs, and traditions. When the war ended, the women brought these new experiences with them back home.

The WAVES’ contributions to the war effort were critical to winning the war. Making up about 2.5 percent of the Navy’s total strength during World War II, these women chose to leave civilian life and take up the structure, routine, and duties of naval service. Brave, bold, patriotic, and adventurous, the WAVES set the foundation for women in the Navy today. While serving in World War II, the WAVES proved their ability to work in new fields, think critically, pay attention to detail, and operate under the highest level of secrecy.

Women’s Armed Service Integration Act (Jun 11, 1948)

Women’s Armed Service Integration Act (Jun 11, 1948)by Library of Congress National Women’s History Museum

Following the war, naval leaders, female officers, and former WAVES lobbied to activate permanent status for women in the Navy. After intense pressure, Congress passed the Army-Navy Nurses Act in 1947, establishing the Navy Nurse Corp as a permanent corp. One year later, President Truman signed the Women’s Armed Service Integration Act in June 1948, disbanding the WAVES and allowing women to receive regular permanent status in the armed forces.

Collage of Women in the Navy Today (Mar 24, 2017)

Collage of Women in the Navy Today (Mar 24, 2017)by U.S Navy National Women’s History Museum

Opportunities for Navy women continued to expand over the next 50 years. In 1978, Congress changed Section 6015 of Title 10, U.S Code, allowing women to receive assignment on non-combat ships. In 1994, women became eligible to serve on combat ships and squadrons.

As of 2016, 19% of the Navy’s enlisted members and 18% of the Navy’s officers were women. Women in the Navy continue to push boundaries and achieve new feats, showing true grit, courage, and patriotism.

Video courtesy of Jeff Malet Photography, Washington, D.C

Credits

National Women's History Museum

www.WomensHistory.org

Exhibit curated and created by Sarah Aillon

Images and sources courtesy of:

Women Veterans History Project, Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and UniversityArchives, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, North Carolina.

WAVES Collection, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.

Elizabeth Reynard Papers, 1934-1962; A-128. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Jericho House, Dennis Historical Society, Dennis, MA.

Veterans History Project, Library of Congress.

World War II Posters, 1942 - 1945, Record Group 44, Library of Congress.

National Youth Administration (NYA) Photographs showing Projects in New England and New York, 1935 - 1942, Record Group 69, Library of Congress.

Official Military Personnel Files, 1885 - 1998, Record Group 24, Library of Congress.

Administrative History of the First Naval District in World War II, 1946 - 1946, Record Group 181, Library of Congress.

Ruth Koczela Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Washington, D.C

La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College, New York, NY.

Jeff Malet Photography, Washington, D.C

Bibliography:

Akers, Regina. The Navy’s First Enlisted Women. Washington, D.C: Naval History and Heritage

Command, 2019.Asal, Alex. “Learning to ‘Be Navy.’” Smith Alumnae Quarterly, (2019): 42-47. https://www.smith.edu/news/waves-smith-college

Cipolloni, Donna. “Remembering Navy WAVES During Women’s History Month.” U.S Department of Defense. Last modified March 3, 2017, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/News/Article/Article/1102371/remembering-navy-waves-during-womens-history-month/

Ebbert, Jean and Mary-Beth Hall. Crossed Currents: Navy Women in a Century of Change. Washington, D.C: Brassey’s, 1999.

Ennis, Lisa. “The WAVES and GSWC: ‘Good for Each Other.’” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 85, no.3 (2001): 461-472.

Godson, Susan. Serving Proudly: A History of Women in the U.S Navy. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Gildersleeve, Virginia. Many a Good Crusade: Memoirs. New York: Macmillan, 1954. 273.

Graf, Mercedes. “Sister Nurses in the Spanish-American War.” Prologue Magazine 34, no.3 (2002): https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/fall/band-of-angels-1.html

Kornblum, Lori. “Women Warriors in a Men 's World: The Combat Exclusion.” Law & Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice 110, no.3-4 (2017): 325-351.

MacGregor, Morris. Integration of the Armed Forces 1940-1964. Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, 2001. https://history.army.mil/html/books/050/50-1-1/cmhPub_50- 11.pdf

Mullenbach, Cheryl. Double Victory: How African American Women Broke Race and Gender Barriers to Help Win World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013.

Patten, Eileen and Kim Parker. “Women in the U.S Military: Growing Share, Distinctive Profile.” Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2011/12/women-in-the-military.pdf.

Ponte, Lucille. “United States v. Virginia: Reinforcing Archaic Stereotypes About Women in the Military Under the Flawed Guise of Educational Diversity.” Hastings Women’s Law Journal 7, no. 1 (1996): 1-84.

Scrivener, Laurie. “U.S Military Women in World War II: The Spar, WAC, WAVES, WASP, and Women Marines in U.S Government Publications.” Journal of Government Information 26, no. 4 (1999): 361-383.

Smith, Lynn. “Former WAVES Recall a Man’s World.” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1992. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-07-13-mn-3711-story.html

“Twenty-five Years of Women Aboard Combatant Vessels.” Navy History and Heritage Command. Last modified April 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/diversity/women-in-the-navy/women-in-combat.html

Ware, Susan. Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth-Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Weatherford, Doris. American Women During World War II: An Encyclopedia. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2010.

Wilcox, Jennifer. Sharing the Burden: Women in Cryptology during World War II. Fort G. Meade: Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency, 2013. https://www.nsa.gov/Portals/70/documents/about/cryptologic-heritage/historical-figures-publications/publications/wwii/sharing_the_burden.pdf

Williams Broome, Kathleen. “Women Ashore: The Contribution of WAVES to US Naval Science and Technology in World War II.” The Northern Mariner 8, no. 2 (1998): 1-20.