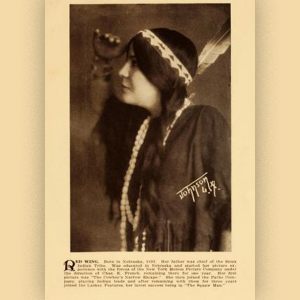

Lilian St. Cyr (“Red Wing”)

On February 23, 1914, Lilian St. Cyr, performing under the name “Princess Red Wing,” became the first Native American actress to appear in a silent film. During her 15-year acting career, she performed in more than 70 films—both shorts and Hollywood features. She was also a fiercely independent woman who spent most of her life promoting Native American culture through art, lectures, and advocacy.

Lilian Margaret St. Cyr was born on February 14, 1884 on the Winnebago Reservation in Nebraska. She was one of six children born to Julia De Cora (ca. 1846-1885), a Winnebago, and Mitchell St. Cyr (ca. 1834-1888), a farmer whose father was reportedly French Canadian and mother a Sauk. While she identified as a member of the Winnebago Tribe, she specifically was Ho-Chunk. Many of her family members were involved in the arts and many were educated off of the Winnebago Reservation. Orphaned in 1888, St. Cyr spent ten years in Indian boarding schools before matriculating to the Carlisle Indian School in 1894. She graduated in 1902.

In 1906, she married James Young Johnson, who later changed his name to James Young Deer. Due to the popularity of dime novels and Wild West Shows in the early twentieth century, the couple began passing as “Plains Indians” in these theatrical productions. They appeared alongside 100 Lakota Sioux in NYC’s Hippodrome Theater in a production called “Pioneer Days: A Spectacle Drama of Western Life." They entertained mostly white crowds by reenacting stagecoach battled and performing the Ghost Dance. Due to these performances, St. Cyr and her husband caught the attention of film directors and the couple became popular actors to play Native American roles in films.

St. Cyr began appearing in small roles in both major silent films and shorts. As she acted, she also made sure she was not used as a prop, and she consulted on films as well. Her first possible appearance in a short film was Kalem’s “The White Squaw” in 1908. A year later, D.W. Giffith hired St. Cyr and her husband as technical consultants for his two films featuring Native Americans. By 1912, her character was so popular that competing film companies created their own “Red Wing” stock characters.

In 1914, St. Cyr made history, not only as a Native American woman but as a film pioneer. She played a leading role in Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Squaw Man.” The film, about an ill-fated marriage between a Ute woman and an Englishman, was the first Western to be made in what is now Hollywood. St. Cyr made her own costumes for the film and her performance received rave reviews by the press and her fellow actors. When St. Cyr, who despite playing a main role was paid far less than the male lead in the film, was told she should be proud to be acting alongside an “$1,000-a-week star” she responded, “‘What about him? He’s working with a one hundred percent American.’” By the time her career ended in 1925, she had served not only as an actress, but a writer, prop maker, costume designer, cultural consultant, and her own stunt woman.

After her film career ended, St. Cyr continued to be involved in promoting Native American culture. Separating from her husband in the 1920s, St. Cyr moved to New York City to join her older sister, Julia. While there, she supported herself and lived independently on the Upper West Side as an educator-performer. She designed, and sometimes sewed, Native American costumes for the F.A.O. Schwartz toy store and the Eaves Costume Company. She also made costumes and regalia for white fraternal organizations, theatrical producers, tribal members, and real and faux Native American performers.

St. Cyr was also involved in advocacy throughout the 1920s and 30s. She helped start the American Indian Community House, which emerged as the leading urban Native resource in the tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, Connecticut). She was involved with the Indian Unity Fraternal Organization, also known as the Indian Unity Alliance, a group that sought to assert the importance of Native American heritage. One of their major goals was to create a National Indian Day as a federal holiday. In an effort to promote the day, St. Cyr and roughly 200 other Native Americans representing many different tribes gathered in Prospect Park in Brooklyn on September 27, 1929 for a show of unity. Throughout the 1930s, St. Cyr continued to lend her name and performance skills to groups and events that sought to promote the general welfare of Native Americans and to promote a National Indian Day.

A pioneer of film, St. Cyr died on March 13, 1974 and is buried in St. Augustine Cemetery in Nebraska. Throughout her life, St. Cyr remained fiercely independent, a woman who shaped her own persona in order to educate others on Native American history and culture.

Aleiss, Angela. “100 Years Ago: Lillian St. Cyr, First Native Star in Hollywood Feature.” Indian Country. February 24, 2014. https://www.aisc.ucla.edu/news/files/Aleiss_LillianStCyr.pdf

Waggoner, Linda M. Starring Red Wing!: The Incredible Career of Lilian St. Cyr, the First Native American Film Star (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019).

MLA – “Lilian St. Cyr ("Red Wing").” National Women’s History Museum, 2020. Date accessed.

Chicago – “Lilian St. Cyr ("Red Wing").” National Women’s History Museum. 2020. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/lilian-st-cyr-red-wing.

Photo:

Photograph of Red Wing published in Who’s Who in the Film World (1914). Johnson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Wing_(actress)#/media/File:Red_Wing_1914.jpg

Further Reading:

Deloria, Philip Joseph. Playing Indian. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1998

Diamond, Neil, Catherine Bainbridge, Jeremiah Hayes, Christina Fon, Linda Ludwick, Clint Eastwood, Robbie Robertson, et al. 2010. Reel Injun.