Unlikely Friends

The opening volleys of the Civil War rang out on April 12, 1861 at Fort Sumter, dividing a country. Over the next four years, battles and politics dislocated thousands of Americans, placing them into theretofore unimaginable situations. For some, the War was an opportunity. Thousands of enslaved men, women, and children fled to Federal territory with little more than the clothes on their backs for the promise of freedom and protection. The immense need faced by the recently enslaved, called Contrabands, aroused individuals and organizations—most affiliated with the Abolitionist Movement—to organize a humanitarian response. Julia Wilbur and Harriet Jacobs answered the call. Thus, two women from opposite ends of the country and social order found themselves brought together.

The dividing line between North and South was drawn just south of Washington, DC, encompassing the small, port town of Alexandria, Virginia. George Washington’s adopted home town voted with the rest of Virginia to secede from the Union. Its proximity to Washington, DC, just across the river, was a threat to the Federal government’s security. Moving quickly, federal troops swarmed the city and placed it under martial law. It remained under Federal control for the duration of the war, much to the chagrin of the city’s loyal, Confederate citizens.

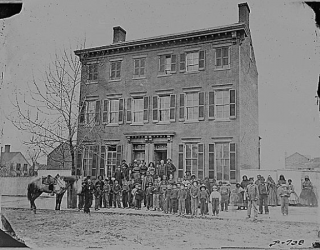

Beginning in 1862, thousands of individuals self-emancipated from slavery by fleeing behind Union lines. They migrated to Alexandria in large numbers, causing a refugee crisis. The city lacked the capacity and resources to feed, house, and care for destitute, sick, and exhausted people. The Federal government built barracks and a hospital to house the refugees, and Northern aide societies collected donations to alleviate the suffering. Julia Wilbur arrived in late 1862 as an agent of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. Wilbur, who had trained and worked as a school teacher, was initially sent to organize a freedman’s school in Washington, DC. Her supervisor sent her to Alexandria instead where she discovered that the need for food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention was equally great.

Harriet Jacobs came to Alexandria for a similar reason but from an entirely different background. While Julia Wilbur grew up in relative affluence in New York State, Jacobs was born a slave in Edenton, North Carolina. Jacobs slipped away from her enslaver’s house in 1835. Her grandmother, who was a freed woman, hid Jacobs in a 3’x7’ crawl space over her porch for seven years, until Jacobs could be smuggled out of town on a schooner. Jacobs spent the next several years after her escape living and working as a nanny in New York. She published her slavery and escape narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl in 1861 to moderate acclaim. While living and working in New York, Jacobs became involved with abolitionist societies and met famed abolitionists Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, who were both impressed by Jacobs’ story. After hearing of the refuge crisis in Alexandria, Garrison encouraged Jacobs to move to Alexandria as an aid worker. She arrived in January 1863.

Harriet Jacobs, 1894.

Jacobs and Wilbur encountered each other soon after Jacobs arrived. Wilbur was surprised, particularly as the two women had met briefly years before in Rochester, New York when both were involved in the City’s anti-slavery community. They were not friends at first, but they soon were brought together by their shared frustration with Alexandria’s military governor, John Slough. Neither cared for his governing tactics, which they decried as cruel and counter-productive. Both women worked long hours to provide for the Contrabands’ basic needs including food, shelter, medicine, and education. Both were outsiders to Alexandria, a community that began the war defiant of the Union but came to despise the Federal government as the occupation wore on and life became increasingly difficult. Few native Alexandrians were interested in socially embracing an abolitionist meddler and an escaped slave. The women’s friendship flourished, fostered by their work, shared goals, and mutual respect.

When the war ended in 1865, Wilbur and Jacobs went their separate ways. Wilbur moved to Washington, DC where she secured a clerical position in the Patent Office. Jacobs and her daughter moved south to continue their Freedmen work before relocating to Boston. After several years in Boston, Jacobs and her daughter moved one last time, in 1877, to Washington, DC, where she opened a boarding house. It was in DC that she reconnected with her old friend Julia Wilbur, who was still working at the Patent Office. They remained friends until Wilbur died in 1895. Jacobs died two years later. Their friendship was forged by circumstance but sustained through respect.