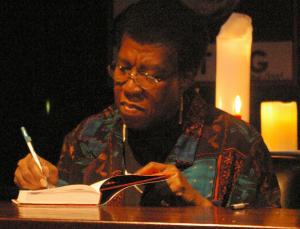

Octavia Estelle Butler

Octavia Butler was a pioneering writer of science fiction. As one of the first African American and female science fiction writers, Butler wrote novels that concerned themes of injustice towards African Americans, global warming, women’s rights, and political disparity. Her books are now taught in schools and universities across the U.S.

Octavia Estelle Butler was born in Pasadena, California in 1947. She grew up poor in a city that, while not segregated legally, was segregated in fact. Her father, who worked as a shoe shiner, died when she was seven and Butler was raised by her mother who worked as a maid and her grandmother. Butler remembered accompanying her mother to work at wealthy homes in Pasadena and having to enter through the back door. Her mother, who only had three years of formal schooling, worked incredibly hard to make sure Butler had more opportunities and a better education than she had.

Butler attended Pasadena public schools where, as a shy and frequently lonely student who struggled with dyslexia, she felt left behind. Her teachers interpreted her slower reading as an unwillingness to do the work rather than a sign of her struggles with dyslexia. When she was given books to read in school, she found them boring and unrelatable, and she begged her mother for a library card. She recalled her mother, “looked surprised and happy. She immediately took me to the library and got me a card. From then on the library was my second home.” She had an endless appetite for stories and frequently made up her own while sitting on her grandmother’s porch. She knew she wanted to write science fiction after seeing a 1954 B-Movie, Devil Girl from Mars, at age nine. She recalled in interviews that two things struck her after seeing it, “Somebody got paid for writing that story!," and "Geez, I can write a better story than that!"

Butler began to find “companionship in words,” and she recalled that by the time she was ten she could be found carrying around a large notebook, writing down stories whenever she got a free moment. Whenever she wrote stories for school, they were so unusual that many of her teachers assumed she had copied them from published works. One teacher recognized her talents and encouraged the then 13-year-old Butler to submit one of her stories to a science fiction magazine for publication. That submission was the first of many and solidified her desire to—and her belief that she could—become a professional writer.

Butler graduated from Pasadena City College with an Associate's Degree in 1968. She then continued taking classes, first at California State University in Los Angeles and then at the University of California at Los Angeles. She took writing classes but also studied anthropology, psychology, physics, biology, and geology, among other subjects. She loved learning and recalled, “You’re always realizing there is so much out there that you don’t know.” She also took a class with science fiction writer Harlan Ellison at the Screen Writers’ Guild Open Door Program. Ellison became a mentor to Butler and encouraged her to attend the Clarion Science Fiction Writer’s Workshop. Before the end of the workshop, Butler had sold her first two stories.

In an interview later in her life, Butler said, “I don't recall ever having wanted desperately to be a black woman fiction writer . . . I wanted to be a writer." Despite her success with the short stories, Butler struggled to get other stories published. She would rise at two A.M. every morning to write and then went to work in a series of odd jobs, including a telemarketer, potato chip inspector, dishwasher, and warehouse worker. After a series of rejections, Butler shifted gears and tried to write her first novel. That first manuscript was purchased by Doubleday and published in 1976. Patternmaster caught people’s attention and became the first in the Patternist trilogy.

Butler wrote 12 more books. Many consider Kindred (1979) a modern-day classic. Kindred tells the story of Dana, a contemporary African American writer who is hurtled backward in time to antebellum Maryland where she must learn to conform to the times in order to survive. Butler heavily researched the book, spending time in Maryland and in the archives to make sure she understood the history and the geography. Butler often said she was inspired to write Kindred when she heard young African Americans minimize the cruelty and severity of enslavement. She wanted younger readers to know not only the facts of enslavement but what it felt like, making sure to humanize those who survived the exploitative institution. Kindred is now a mainstay in many high school and college classrooms.

Butler disagreed with the idea that African American characters only belonged in science fiction if their race was crucial to the plot, which was the predominant way African American characters were included in the genre when she began writing. She once said in an interview, “I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing. I can write my own stories and I can write myself in.” Butler’s writing became an early pillar of the subgenre of Afrofuturism, which UCLA defines, “as a wide-ranging social, political and artistic movement that dares to imagine a world where African-descended peoples and their cultures play a central role in the creation of that world”.

Butler won numerous prestigious awards for her writing. In 1995, she was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” Grant—the only science fiction writer to receive this award. She won Nebula and Hugo Awards, the two highest honors for science fiction, a PEN Lifetime Achievement Award, and the City College of New York’s Langston Hughes Medal in 2005. As a pioneer in science fiction, she opened up the genre to many other African American and female writers.

Butler died suddenly in her home in Seattle from a fall on February 24, 2006. Since her passing, her books have continued to rise in popularity and many have forthcoming TV or movie adaptations. She once told PBS that her oath was, “‘Do the thing that you love and do it as well as you possibly can and be persistent about it.’” Readers are all the better for her dedication to and love of words.

“About the Author,” Octavia E. Butler, https://www.octaviabutler.com/theauthor.

“Success Stories: Octavia Butler, Award-Winning Author,” The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, https://dyslexia.yale.edu/story/octavia-butler/.

“Octavia Butler: Writing Herself into the Story,” Morning Edition, NPR, July 10, 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/07/10/535879364/octavia-butler-writing-herself-into-the-story.

Abby Aguirre, Octavia Butler’s Prescient Vision of a Zealot Elected to ‘Make America Great Again,’” The New Yorker, July 26, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/books/second-read/octavia-butlers-prescient-vision-of-a-zealot-elected-to-make-america-great-again.

Delan Bruce, “Afrofuturism: From the Past to the Living Present,” UCLA Newsroom, September 3, 2020, https://newsroom.ucla.edu/magazine/afrofuturism.

MLA – Rothberg, Emma. “Octavia Butler.” National Women’s History Museum, 2021. Date accessed.

Chicago – Rothberg, Emma. “Octavia Butler.” National Women’s History Museum. 2021. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/octavia-butler.

Photo Credit: Nikolas Coukouma, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=602976.

Stephen Kearse, “The Essential Octavia Butler,” The New York Times, January 15, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/15/books/review/the-essential-octavia-butler.html.