Pedaling the Path to Freedom

Bike messenger in bloomers for the National Women's Party Headquarters.

Although it seems very unlikely, bicycles had a revolutionary impact on the women’s movement of the early 20th century. Bicycles promised freedom to women long accustomed to relying on men for transportation. Suddenly, the relatively inexpensive and readily accessible technological innovation gave women more control over where they went and when.

Bicycles took American consumers by storm in the 1890s. At the turn of the century, trains, automobiles, and streetcars were growing in use in urban areas, but people still largely depended on horses for transportation. Horses, and especially carriages, were expensive and women often had to depend on men to hitch up the horses for travel. While horses were cheap to maintain in rural areas, owning a horse in a city was expensive, with extra costs for housing in stables and the upkeep of the animals. Surrounded by inefficient and expensive forms of travel, bicycles arrived in cities with the promise of practicality and affordability. Bicycles were relatively inexpensive and provided men and women with individual transportation for business, sports, or recreation.

Changes in style

The first wave of the women’s rights movement was well underway by the peak of the American bicycle craze in the 1890s. The bicycle, in many ways, came to embody the spirit of change and progress that the women’s rights movement sought to engender. In 1895, Frances Willard, leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement, published a book entitled A Wheel within a Wheel: How I learned to Ride the Bicycle, which chronicled her quest to learn to ride the bicycle late in life to aid her deteriorating health. Although she died just three years later, Willard’s reflections on bicycle riding encouraged others. She decried the cumbersome and restrictive fashions of the day and called for more sensible and practical fashion for female bicyclists. Willard wrote:

“A woman with [bustle] bands hanging on her hips, and dress snug about the waist and chokingly tight at the throat, with heavy trimmed skirts dragging down the back and numerous folds heating the lower part of the spine, and with tight shoes, ought to be in agony. If women ride, they must…dress more rationally… If they do this, many prejudices will melt away. Reason will gain upon precedent and ere long the comfortable, sensible, and artistic wardrobe of the rider will make the conventional style of women’s dress absurd to the eye and un-durable to the understanding.”

Women soon found that the traditional dress of corsets, bustles, and long voluminous skirts impeded the supposed ease of bicycle travel. As Willard foreshadowed, this prompted a change in women’s fashion including lighter skirts, bloomers (sometimes known as divided skirts), or even trousers to allow for a less cumbersome ride. Bicycle riding came to embody the individuality women were working toward with the suffrage movement. It also gave women a mode of transportation and clothing that allowed for freedom of movement and of travel.

Independence and self-reliance

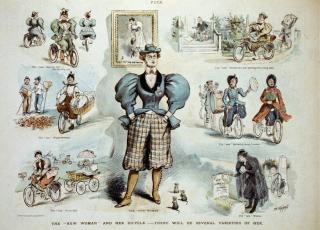

Bicycles came to symbolize the quintessential “New Woman” of the late 19th century. The Progressive Era was a time of great social and cultural change in the United States and the “New Woman” embodied this change. Images reflected many of the new opportunities for careers and education that were becoming available. The “New Woman” was deemed to be young, college educated, active in sports, interested in pursuing a career, and looking for a marriage based on equality. She was also almost always depicted on a bike.

In an 1895, at the age of 80, suffragist leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton claimed that “the bicycle will inspire women with more courage, self-respect, self-reliance…” Stanton predicted the power of the bicycle in transforming the lives of women, realizing that the independence women were gaining because of this invention would allow for growth in other areas of their character. Having the ability to be fully self-reliant, often for the first time in their lives, would encourage women to be more courageous in other areas, such as demanding voting rights. Stanton’s friend and fellow suffragist leader, Susan B. Anthony, echoed Stanton’s sentiments. At 76, Anthony opined, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

Women today, especially in the developing world, are gaining this same feeling of freedom and self-reliance as the “New Woman.” Bicycles allow women an escape from sexual harassment too often encountered on public transportation and provide an inexpensive means of travel in countries where access to automobiles and public transportation are limited. Multiple aid organizations donate bicycles to women as a means of liberation and teach them the skills to fix their own bike so they do not have to rely on men for help. Almost 200 years after its invention, bicycles continue to have a positive impact on women’s lives.

Originally published May 1, 2012.

Updated and republished by Kenna Howat, Program Assistant, June 2017

LeBlanc, Robin M. Bicycle Citizens: The Political World of the Japanese Housewife. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1999.

Macy, Sue. Wheels of Change: How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom (With a Few Flat Tires Along the Way). Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2011.