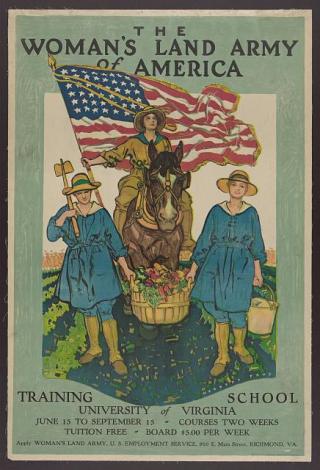

Women’s Land Army of World War I

World War I Poster

In 1917, the United States entered World War I in support of the Allies, which included Britain and France. The entrance of America into this all-consuming war, signaled great changes on the home front as the country geared up for war. Many young men left work on the farms to join the services or obtain better paying jobs in the defense industry. The shift of men away from agriculture left a void on the farms, which the government had a difficult time filling.

University of Virginia Training School

During World War I, Britain created the Women’s Land Army through which young women worked on farms in order to support the changing needs of the country’s agricultural sector. Taking their cue from the British Land Army, some women’s universities in the United States began training women to work the land in order to support the agricultural needs of the country. Chief among these institutions were Vassar, Mount Holyoake, and Bryn Mawr Colleges.

One of the most influential schools to contribute to the creation of the Women’s Land Army in America (WLAA) was Barnard College. In the summer of 1917, under the leadership of Dean Virginia Gildersleeve and Associate Professor of Geology, Dr. Ida H. Ogilvie, the school formed the Women’s Agricultural Camp in Bedford, New York, outside of New York City. Many of those in attendance were current and former students of Barnard College. In total, 142 women attended the camp for four months, which provided lectures, training, and hands-on experience on local farms.

Women who enrolled in programs, such as those created at Barnard College, paid a fee for their training. The cost involved in attending meant that middle and upper class women made up the majority of those enrolled in courses. Working class women could little afford to pay for such training. However, some working class women temporarily joined in agricultural work during harvest periods.

The success of the Barnard College training program laid the foundation for the WLAA later that year. In December 1917, the Advisory Council of the Women’s Land Army of America meet and officially brought the WLAA into being. Harriet Stanton Blatch was appointed the Director of the WLAA. The daughter of suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Blatch’s appointment and involvement with the organization symbolized its close ties to the suffrage movement. Many of the organizers and women involved in working on the land were also suffragists. These women believed that by patriotically serving their country through their agricultural work, they could draw attention to the suffrage movement.

World War I Poster

The Women’s Land Army of America was set up in forty states and the District of Columbia. Historians estimate between 15,000 and 20,000 women took part in the WLAA across the country. Although President Woodrow Wilson lent his support to the organization in 1918, the government did not grant the WLAA any federal funding. The money needed to run the national headquarters in New York City and the subsidiary state branches of the group were financially supported by private contributions, many given by women’s organizations.

World War I "Farmerette"

Women who joined the WLAA became known as “farmerettes”. The organization instituted an eight-hour day and demanded that farmers pay women the same wages as male laborers. Women aged 18 and over were eligible to join the WLAA as long as they passed a physical exam to prove that they were fit enough to tackle the demands of agricultural work. Uniforms varied widely, but women tended to wear a blue or khaki smock, a hat, and sturdy shoes. Women were most often placed on either single farms or in community agricultural settings.

Farmers and the media did not at first look favorably on employing women in agricultural work. Many felt that these young, urban women would not be able to cope with the difficult working conditions on a farm. However, the women of the WLAA proved to be capable and successful on American farms.

When World War I ended in 1918, the future of the WLAA was in limbo. Many within the organization wanted to continue the program. But financial difficulties hampered the work of the WLAA after the war. At the beginning of 1920, the organization was formally disbanded.

By: Dr. Kelly A. Spring

2017

Works Cited:

Books

- Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women’s Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013.

- Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: the Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C. : Potomac Books, c2008.

Websites

- AAUW. “Trading Pencils for Plows: College Women Save Farms during WWI.” Written August 5, 2014. Accessed September 20, 2017. http://www.aauw.org/2014/08/05/trading-pencils-for-plows/

- Barnard Archives and Special Collections. “The Barnard ‘Farmerettes’ of World War I.” Written December 1, 2009. Accessed September 20, 2017. https://barnardarchives.wordpress.com/2009/12/01/the-barnard-%E2%80%9Cfarmerettes%E2%80%9D-of-world-war-i/

- Weiss, Elaine F. “Before Rosie the Riveter, Farmerettes Went to Work.” Smithsonian.com. Written May 28, 2009. Accessed September 21, 2017. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/before-rosie-the-riveter-farmerettes-went-to-work-141638628/

Additional Resources:

- University of California. “The Victory Grower.” Accessed September 22, 2017. http://ucanr.edu/sites/thevictorygrower/Historical_Models/Womans_Land_Army_of_America,_ca_WWI/