The 14th and 15th Amendments

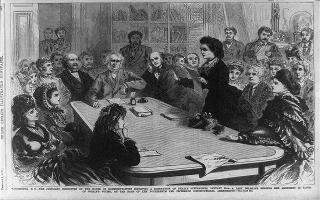

House of Representatives Committee Receiving a Delegate in Favor of Woman’s Voting.

Three amendments passed after the Civil War transformed the women’s rights movement. The Thirteenth Amendment, passed in 1865, made slavery illegal. Black women who were enslaved before the war became free and gained new rights to control their labor, bodies, and time.

The Fourteenth Amendment affirmed the new rights of freed women and men in 1868. The law stated that everyone born in the United States, including former slaves, was an American citizen. No state could pass a law that took away their rights to “life, liberty, or property.”

The Fourteenth Amendment also added the first mention of gender into the Constitution. It declared that all male citizens over twenty-one years old should be able to vote. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment affirmed that the right to vote “shall not be denied…on account of race.”

The insertion of the word “male” into the Constitution and the enfranchisement of African American men presented new challenges for women’s rights activists. For the first time, the Constitution asserted that men—not women—had the right to vote. Previously, only state laws restricted voting rights to men. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote, “If that word ‘male’ be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out.”

Activists bitterly fought about whether to support or oppose the Fifteenth Amendment. Stanton and Susan B. Anthony objected to the new law. They wanted women to be included with black men. Others—like Lucy Stone—supported the amendment as it was. Stone believed that women would win the vote soon. The emphasis on voting during the 1860s led women’s rights activists to focus on woman suffrage. The two sides established two rival national organizations that aimed to win women the vote.

By Allison Lange, Ph.D.

2015