Mamie Phipps Clark

Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark was a pathbreaking psychologist whose research helped desegregate schools in the United States. Over a three-decade career, Dr. Clark researched child development and racial prejudice in ways that not only benefitted generations of children but changed the field of psychology.

Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark was born on April 18, 1917, in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Growing up in the Jim Crow South, Clark went to segregated elementary schools and witnessed the violence of racism firsthand. She recalled that she knew she was African American from childhood since “you had to have a certain kind of protective armor about you, all the time … You learned the things not to do…so as to protect yourself.” Yet Clark felt she had a “privileged” childhood compared to other African American children due to her parents. Her father, Harold H. Phipps, was a well-respected physician—a rare occupation for an African American person to hold at the time. Due to her father’s financial success, her mother, Kate Florence Phipps, was able to stay home with Clark and her younger brother. Kate’s ability to stay home was also rare for African American women at the time, since many had to take on labor or service jobs to make ends meet. Clark credited this warm, supportive, and protective childhood environment for her later success.

In 1934, Clark graduated high school and received multiple scholarship offers from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Despite the expense of sending a child to college, a burden made worse by the Great Depression and the limited college options for African Americans, Clark’s parents were determined she get a degree. Clark went to Howard University in Washington, D.C. on a merit scholarship. She knew she wanted to help children. Originally studying math and physics to become a teacher, Clark felt the professors in those departments were unsupportive and cold. Then she met Kenneth Clark, a psychology student at Howard; the meeting was, Clark later described, “prophetic.” Kenneth introduced Clark to professors in the Psychology Department and encouraged her to pursue psychology. Despite knowing she would have difficulty finding a job as an African American woman in the field, she studied it and graduated magna cum laude with a B.A. in Psychology in 1938. This was also the beginning of a collaboration and relationship with Kenneth that would last the rest of Clark’s life.

The summer between graduation and beginning a master’s in psychology at Howard, Clark worked as a secretary for Charles Hamilton Houston, an NAACP lawyer whose office served as the planning ground to legally challenge racial segregation across the country. When she began her Masters, Clark was influenced by the law office’s work and the work she did at an all-African American nursery school. Her Master’s Thesis, “The Development of Consciousness in Negro Pre-School Children,” surveyed 150 African American pre-school aged boys and girls from a Washington, D.C. nursery to explore issues of race and child development. Specifically, she wanted to understand at what age African American children became aware that they were African American. From 1939 to 1940, Clark and Kenneth—who had begun a Ph.D. in Psychology at Columbia University in 1937—published three major articles featuring her thesis work.

In 1940, Clark began a Ph.D. in Psychology at Columbia University. Joining Kenneth, with whom she had eloped during her senior year at Howard, the two became the only African Americans in the department. Clark specifically went to Columbia to work with Professor Henry Garrett, a scientific racist and eugenicist; Clark wanted to challenge him and his thinking personally. When Clark started her graduate studies, the field of psychology was still characterized by scientific racism—a pseudoscientific theory supporting white supremacy. While Clark pursued her Ph.D., she also raised her and Kenneth’s daughter, Kate, while Kenneth took research trips. The two continued collaborating together, receiving prestigious Julius Rosenwald Fellowships (established to fund, support, and advance the achievements of African Americans) in 1940, 1941, and 1942 to study racial identity in children. Clark became the first African American woman to graduate Columbia with a Ph.D. in 1943. The couple’s second child, Hilton, was born the same year.

After graduation, Clark was unable to find an academic job despite her accomplishments. Clark first took a job as an analyst at the American Public Health Association and then as a research psychologist at the U.S. Armed Forces Institute. In both jobs, she felt she was in a “holding pattern.” She then became the testing psychologist at the Riverdale Home for Children, a refuge for homeless girls. That work made her realize there was a lack of services for African American children in Harlem. She advocated for more services and resources but was met with silence from the city government and others. Taking matters into her own hands, the Clarks started the Northside Center for Child Development in 1946; it was the first and only organization in the city that provided mental health services to African American children. Northside offered psychological testing, psychiatric services, social services, and academic services and became a center of activism and advocacy for Harlem and its residents. Clark ran Northside until her retirement in 1979; the center continues today.

Based on her graduate research, Clark conceived of and implemented “The Doll Test” in the 1940s. In it, the Clarks looked at 253 African American children aged three to seven: 134 attended segregated nursery schools in Arkansas and 119 attended integrated schools in Massachusetts. Shown four dolls (two with white skin and blonde hair, two with brown skin and black hair), the children were asked to identify the race of the doll and which they wanted to play with. Overwhelmingly, the children wanted to play with the white doll and assigned it positive traits. The Clarks concluded that African American children formed a racial identity by age three and attached negative traits to their own identity, which were then perpetuated by segregation and prejudice. It was a pathbreaking study.

Due to this work, Clark served as an expert witness, testifying in many school desegregation cases. In one, she testified against her Ph.D. advisor, Henry Garrett, who argued in favor of segregation. In the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which ended school segregation in the United States, NAACP lawyers used Clark’s research and expert testimony in their successful arguments. While history books credit Kenneth with “The Doll Test,” he even said “the record should show [it] was Mamie’s primary project that I crashed. I sort of piggybacked on it.”

Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark died of lung cancer on August 11, 1983, at age 66. She was survived by her husband Kenneth, who passed away in 2005.

“Mamie Phipps Clak, PhD, and Kenneth Clark, PhD,” American Psychosocial Association, 2012, https://www.apa.org/pi/oema/resources/ethnicity-health/psychologists/clark

Leila McNeill, “How a Psychologist’s Work on Race Identity Helped Overturn School Segregation in 1950s America,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 26, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/psychologist-work-racial-identity-helped-overturn-school-segregation-180966934/

Marie Koesterer, “Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark, Segregation & Self-esteem,” Webster University, http://faculty.webster.edu/woolflm/mamiephippsclark.htm

Ronald Smothers, “Mamie Clark Dies; Psychologist Aided Blacks,” The New York Times, August 12, 1983, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1983/08/12/096551.html?pageNumber=79

MLA – Rothberg, Emma. “Mamie Phipps Clark” National Women’s History Museum, 2022. Date accessed.

Chicago – Rothberg, Emma. “Mamie Phipps Clark” National Women’s History Museum. 2022. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mamie-phipps-clark.

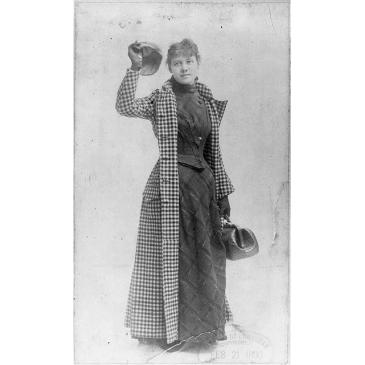

Image Credit: Cropped from Charlotte Brooks, "Minnijean Brown at the home of her host family, Mr. & Mrs. Kenneth Clark, of Hasting-On-Hudson, New York," 1958. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009632169/.

Black History Month, “Fulfilling Black Children’s Lives—Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark,” The British Psychological Society, October 16, 2020, https://www.bps.org.uk/blogs/black-history-month/mamie-phipps-clark

“A Revealing Experiment: Brown v. Board and ‘The Doll Test,’” NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, https://www.naacpldf.org/ldf-celebrates-60th-anniversary-brown-v-board-education/significance-doll-test/

“Kenneth and Mamie Clark Doll,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/brvb/learn/historyculture/clarkdoll.htm

“Kenneth Clark,” Notable New Yorkers, Columbia University Libraries Oral History Research Office, 2006, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/nny/clarkk/profile.html

Stephan N. Butler, “Mamie Katherine Phipps Clark (1917-1983),” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, March 12, 2021, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/mamie-katherine-phipps-clark-2938/